“An alternative to a police response” — this was how Andrea Westbrook, a PhD student in the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work (FIFSW), described the Toronto Community Crisis Service (TCCS). Currently, Westbrook manages the TCCS team operating out of the Gerstein Centre — a social services organization in downtown Toronto and one of TCCS’ four hubs.

On January 16, at a lecture event in the FIFSW building, Westbrook discussed her work, which focuses on providing alternatives to calling the police when people experience mental health crises. Westbrook, who is registered as a social worker, described the importance of providing alternatives and the organization’s plans for the future.

The Toronto Community Crisis Service

The TCCS launched as a pilot program in March 2022. Several organizations — including the Canadian Mental Health Association, the 2-Spirited People of the 1st Nations, TAIBU Community Health Centre, and the Gerstein Crisis Centre — lead the project, which they founded in collaboration with the City of Toronto. The TCCS aims to treat mental health crises as public health events instead of public safety issues by providing direct mental health and substance use support.

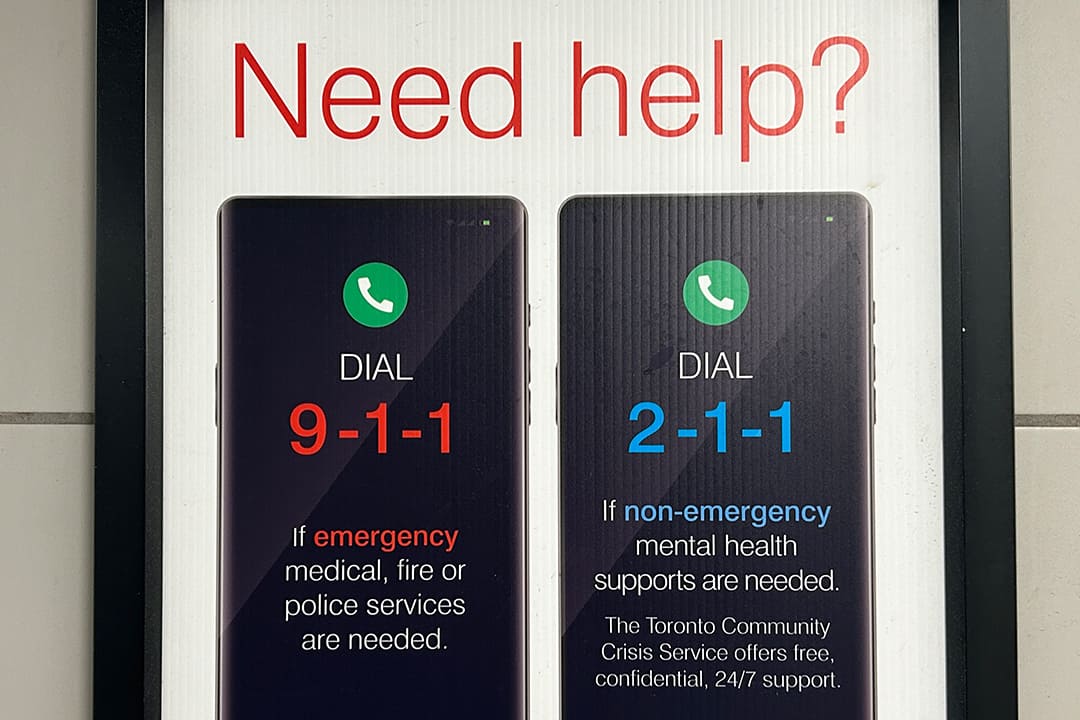

When someone calls 911 or 211 about a mental health crisis, a dispatcher will inform them about the TCCS. People aged 16 and above in four regions — including much of downtown Toronto, north Etobicoke, and Scarborough — can contact the TCCS crisis response team, which provides an alternative to policing to people in need of their assistance.

The TCCS also follows a “No Wrong Door Approach,” where it helps people access a variety of governmental and community-based resources, including future mental health and medical assistance.

Why establish the TCCS?

During her talk, Westbrook discussed how the current police approach often fails to serve people with mental health issues. She noted the need to reconsider how we conceive of violence, citing research showing that people often see people with mental illness as dangerous. “Your first instinct might be that person might hurt me, I’m going to call 911,” she said.

However, she noted that Canadians with mental health issues disproportionately experience violence themselves: “violence from within community, violence at the hands of law enforcement, violence in the hands of our mental health system, as well… So [think] about how our approaches to responding to someone in crisis are, in fact, making people less safe.”

The CBC reported that, from 2000 to 2018, 70 per cent of Canadians killed by the police faced challenges with mental health or substance use disorder, with an overrepresentation of Black, Indigenous, and person of colour (BIPOC) people. “When we have a justice response to a mental health crisis, we’re going to see higher levels of violence,” she said.

According to Westbrook, the TCCS aims to provide assistance to people of all backgrounds, particularly given the “catastrophic impacts” that systematic over-policing has on BIPOC communities.

The TCCS’ approach differs from that of the police, who do not necessarily ask for people experiencing mental health crises for consent before intervening. Police intervention may lead to violence and incarceration for mentally impaired individuals. Westbrook noted that people with mental health diagnoses, cognitive impairments, and disabilities are overrepresented in the criminal justice system.

How has the pilot program fared?

According to Westbrook, within the last year, the Gerstein Centre alone received 2,600 calls and only needed to call the police for backup on just two per cent of these calls.

The organization has also gone on to work with police programs, educating them on how to respond to different crisis calls. Now past its two-year mark, the TCCS plans to launch its services city-wide in July 2024.

No comments to display.