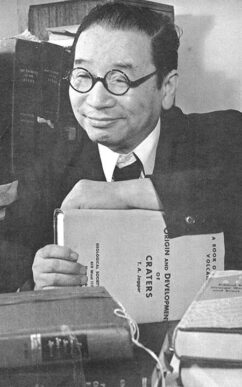

It was 1936, right in the middle of the Great Depression, when Japanese labour activist Toyohiko Kagawa gave a lecture at U of T that would inspire a group of students to form Campus Co-operative Residence Incorporated — what is now Canada’s oldest continuous co-op housing entity.

The U of T Campus Co-operative leased a house on St. George Street that is now the School of Graduate Studies. Within five years, one house had become five. Then, five turned into 30.

Amid the Great Depression, the co-operative movement seemed hopeful. Co-operatives had been sprouting up across Canada, and they took every form imaginable: co-operative fishing organizations, co-operative health facilities, co-operative recreation, and co-operative film clubs. In Japan, Kagawa tendered a similar co-operative movement and helped it flourish into a movement of six million workers.

The rise and fall of the co-op

Kagawa was a staunch advocate for co-op housing, and he also saw workers’ daily economic struggles as an integral component of his religious ideals. His book Brotherhood Economics etched out his plan for the grand unification of Christianity, the peace movement, and the co-operative movement into one powerful force: “Christ put God first,” Kagawa wrote, “but in doing so he did not ignore economics.”

By the 1970s, the co-operative housing model was taking root across Canada. John David Hulchanski, a professor of Housing and Community Development at U of T, told The Varsity, “The federal government in 1971 had announced a pool of money for innovation in co-op housing… And sure enough, it works.” Residents could own and manage co-ops themselves, and could draw on the funding when they ran into financial difficulties.

But such optimism would soon prove premature. The 1970s was a difficult time for the U of T campus co-op — debt piled up from a failed experiment in forming a new independent college, and buildings started to fall into disrepair.

It was the 1990s that finally punctured the Kagawian economic utopian bubble. The co-operative movement in Japan began to experience pressures from a liberalizing economy encouraging entrepreneurial farmers to leave the co-operative behind. Back in Canada, the economic recession of the 1990s hollowed out the campus co-op as vacant rooms created never-ending operating deficits.

“Governments were doing everything they [could] to keep housing in the marketplace,” Hulchanski explained. Then 1995 came, and the program disappeared. Neither the federal nor any of the provincial governments has funded any co-operative housing projects in Canada in decades.

The future of co-op at U of T

The U of T co-op has now been reduced to 23 homes, but it has not disappeared. Cyrus Al-Zayadi, a masters student in evolutionary anthropology and the treasurer of the Campus Co-Operative Residence, told The Varsity that it maintains itself with almost no support from government, and absolutely no support from U of T. The co-op stays afloat, charging just $650 to $800 for a single room, and in 2019, even acquired a new home for the first time in decades.

The co-op was forced to sell the home, however, due to high vacancy rates during the pandemic. Still, Al-Zayadi noted that applications have spiked since the return of in-person classes.

Al-Zayadi has lived in the U of T co-op for over three years. “I was always a very shy person, especially initially when I moved in. Through time, living in a co-op allowed me to break out of my shell,” Al-Zayadi told The Varsity. “There’s an air of camaraderie between everyone. We spend time together, we organize social outings together.”

Hulchanski noted that non-market housing is essential to address households at the bottom of the income spectrum. 96 per cent of Canadian households rely on the private market for housing, due to the scarcity of non-market options like co-ops and social housing.

Will the co-op movement return?

Kagawa’s dream for co-operative housing may be having a resurgence. In 2022, Canada announced a $500 million fund to expand co-operative housing — its largest federal investment in co-op housing in 30 years. The money from this fund is expected to build around 6,000 units. This is a start — but Hulchanski noted that this contribution is nothing compared to Canada’s past social housing commitments.

The U of T campus co-op has also turned a corner after the difficult pandemic years. “In my time, we’ve gone from having a $200,000 deficit to a $30,000 net surplus,” Al-Zayadi said. In the short term, he explained, the co-op is prioritizing repairs to existing properties, but expansion is part of its 10-year plan.

“It gives me a lot of optimism and hope,” Al-Zayadi said. “Not only can we make this work, but we can reach out to other people and tell them you don’t have to suffer like this anymore. There is a better way of doing things.”

No comments to display.