Content warning: This article mentions sexual violence and torture.

The ’60s and ’70s were a fascinatingly horny period for Japanese cinema. Just a decade after the first kiss was shown in a Japanese film — which was coyly obstructed by a strategically placed umbrella — hot babes were suddenly available on every screen with their legs spread wide open, signalling a shift in cultural attitudes. The explosion of borderline-pornographic films produced during this era is called ‘pinku,’ or ‘pinky cinema’ — a deceptively cute name for the salacious genre.

The term ‘pinku’ covers a wide range of Japanese theatrical films that first emerged in the 1960s, which deal with extremely sexual content. Much like the ‘sexploitation’ phenomenon in the US, pinku films were typically low-budget, B-grade movies produced by small studios. Although they ostensibly revolved around a plot, the main allure of pinku was titillating displays of flesh.

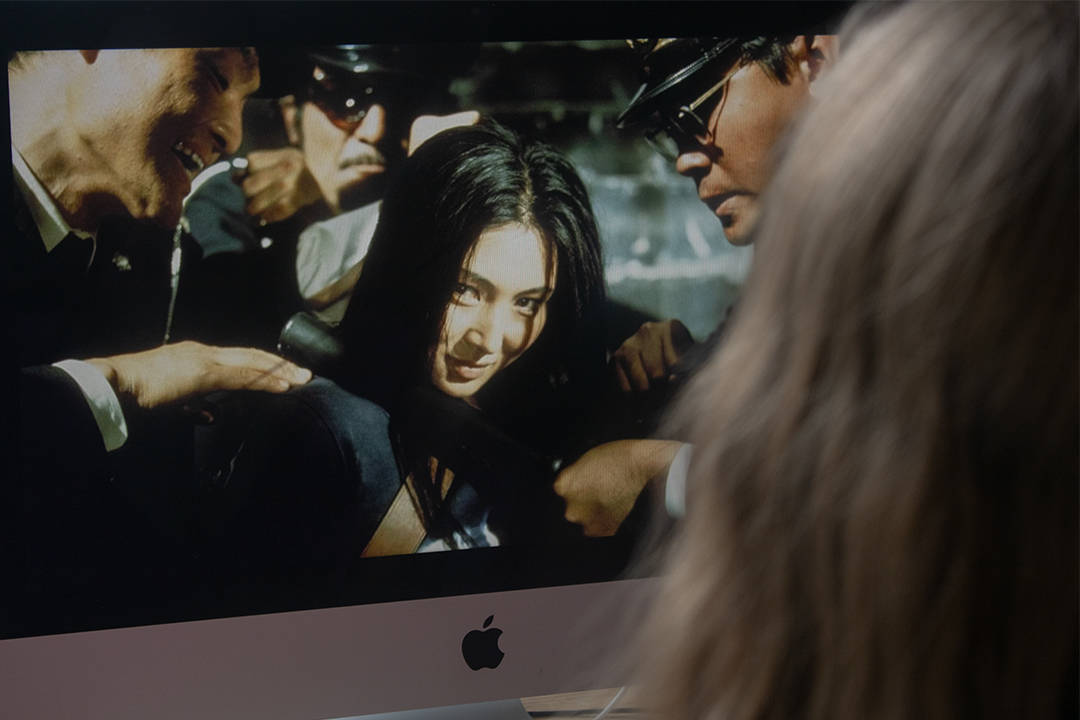

Despite their lecherous premise, some pinku films are surprisingly rife with leftist politics and subversive gender dynamics. Shunya Itō’s Female Prisoner (1972–1973) series, for example, channels its progressive message through Matsu (Meiko Kaji), a cunning woman who is betrayed and imprisoned by her former lover, a crooked cop. Refusing to stay subservient — as so many women are conditioned to — Matsushima literally grits her teeth and perseveres through carceral injustice in hopes of one day gutting her ex.

Her body is put through excessive labour and torture, testified to by grotesque scars that run across her curves. Despite the sadistic games played by men prison guards and the scathing remarks from her fellow inmates, Matsushima is unwavering; each time she is touched and abused, her pretty brown eyes turn toward the camera, petrifying the characters who assault her — and us, the audience, by extension — with a low-lidded, seething glare.

Hers is an oppositional gaze so sharp that any viewer’s skin would pebble and stomach lurch. Perhaps, as much as looking is an exercise of subjugation, it can also be a form of resistance; to lock eyes with your rapist, matching his objectifying dead stare with a look pulsating with repulsion, is profound. For a society where demureness in women is held in high regard, Matsushima’s defiance spits on Japan’s traditional gender roles by refusing to let anyone dominate her spirit.

Norifumi Suzuki’s Sex & Fury (1973) is another interesting case of politics being used as a vessel for visual pleasure — or perhaps the other way around. Starring hard-edged Reiko Ike as Ocho, the plot follows her quest to avenge her late father, who was murdered in a supposed mugging.

Notable is the inscription of Bushido values in Ocho’s character. Touting courage, determination, and self-sacrifice, the samurai code of conduct has informed modern Japanese society in very gendered ways. For a woman such as Ocho to embody it to its fullest, through her steadfast filial piety and righteousness, makes a statement that the strict division of gender roles is a little bit more malleable.

Suzuki’s push against gender is paired with an explicit anti-imperialist critique of Western money in the form of a beautiful British spy named Christina (Christina Lindberg), who travels to Japan to corrupt politicians and steal military secrets. Suzuki is not shy with his nationalism here. The British characters are depicted as snooty individualists who infect Japanese society with their ‘otherness.’ This difference is accentuated by the stiff tailored suits they wear, in contrast to Ocho’s flowy kimonos. Clearly, these images are intended to accuse Britain of its history of imperialism in East Asia during the Meiji period.

Itō and Suzuki’s work feel remarkably empowering — until, eventually, a woman character strips naked for no particular reason, or makes sensual noises while completing the most banal of chores, reminding us once again that we are watching porn directed by a man, and not a dissection of women’s sexuality by Catherine Breillat. Pinku is interesting for this exact reason. The constellation of complex and provoking political themes and sexploitation are hard to reconcile at first. Contradictions define the genre — even the name ‘pinku’ connotes innocent femininity, which is absolutely not the case.

The tensions of pinku intensify when considering the practices. Pinku theatres, much like Toronto’s sketchy porn shops, used to be everywhere in Japan’s red light district. With the content mainly catered to men’s lust, it is unsurprising that viewers were predominantly men — I can only imagine the small cramped rooms filled with a strange pungent odour. Women rarely sat in the audience, and if they did, the erotically charged space meant they faced many unsolicited gazes or touches. Ironically, then, the gendered subject of these tales of empowerment and sexual liberation was alienated from the very films they were supposed to identify with.

So how should we think about the politics of pinku? Is its sleazy imagery merely a marketing ploy intended to draw audiences into the political orbit? Or, more convincingly, do its politics provide a cover of respectability to detract from pornography’s ‘low brow’ status?

Despite these complexities, it would be silly to completely dismiss pinku. The existence of this genre is itself subversive. In contrast to the state’s decidedly Puritan vision for post-war Japan, based on innocence and heteronormative divisions, these films encouraged the nation to indulge in its sexuality. Radical desires and unabashed yearning marked the pinku project. After the despicably savage Second World War, the pinku genre demonstrated that the path to moving forward wasn’t through sterility and innocence but in acknowledging and embracing society’s own baseness.

No comments to display.