Content warning: This article mentions suicide.

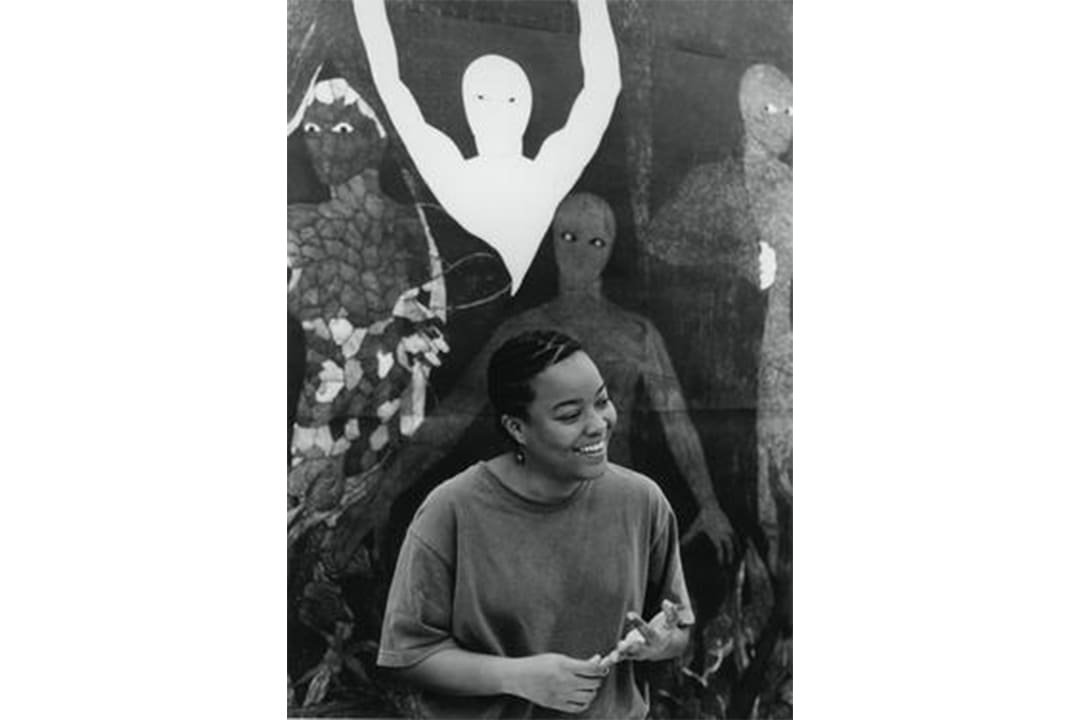

True inspiration, possessing both power and fragility, and capable of transcending assumptions to reveal an intrinsic spirit — the autonomous, technically adept, and sacred creations of Afro-Cuban printmaker Belkis Ayón (1967–1999) hold a wellspring of appreciating how one conveys one’s needs as an artist and as a human.

For those who regard art as the paramount language for the human condition, a retrospective of Ayón’s art is indispensable. She intimately comprehends the mechanics of influence, reference, and exposition, seamlessly weaving the composition of life into art memorably.

Born in Havana, Ayón was an applauded printmaker and teacher active in the fleeting decades of the post-modernist art period and the Período especial en tiempos de paz — a term that roughly means “special period in the time of peace” — in Cuba.

Even in her childhood, during an economically depressed period in Cuba, her talent was not overlooked. Starting at the age of 12, she attended prestigious art institutions in Havana and eventually became a teacher at Instituto Superior de Arte de la Habana (ISA), where she got her Bachelor of Arts in printmaking.

This kind of routine and discipline inherent in the practice of art cultivates true masters like Ayón. For any artist, discipline is a manifestation of spirit. There’s a symbiotic relationship between movement and representation, and that relationship underscores the inevitability of change within the artistic journey.

Collagraphy: Ayón’s medium of artistic expression

Ayón’s brilliant visual compositions cannot be separated from the socioeconomic landscape of Cuba during her time, particularly the tumultuous Período especial en tiempos de paz beginning in 1991 amid the collapse of the Soviet Union. During this era, Cuba felt an economic and resource depression fuelling rationing and social demonstrations. The reality of this period made the reality of Ayón’s art indeed a poignant political response to the scarcity of resources, which compelled her to harness creative ingenuity to an intimate use of visuals and symbols in her work.

Her chosen medium was collagraphy, which she defined as an engraving process consisting of a type of printed collage formed from various materials arranged and pasted on cardboard supports. Collagraphy takes a lot of physical intricacy and a nuanced understanding of the texture that comes out of this art medium. One advantage of collagraphy is that it allows an artist to produce works in quantity during a period of fewer resources.

Through collagraphy, Ayón captured the essence of conflicts caused by her reality and provided a powerful commentary on the human condition amid adversity. At this point, her work became more monumental in its composition, redrawing a space to confront the censorship, violence, exclusion, inequities, and power structures of late twentieth-century Cuba.

The sense of drama that unfolds in her compositions is portrayed by a range of lightness and darkness, which grows bolder in her work as she progresses in her artistic career. These monochromatic colours of black, white, and grey are employed to characterize the silhouettes of her symbols, where the inspired composition begins the mystery.

Ayón’s inspiration from West African spiritual traditions

Drawing from religious traditions of the Cross River region in West Africa, the Abakuá Society emerged in 1836 as a clandestine force among young Afro-Cuban men, particularly in Havana, as a defiant response to the dehumanization of slavery and oppressive regimes.

Ayón leaned heavily on the mythology of Abakuá, a society that was forbidden to women. While researching its secretive practices, she encountered stories of the goddess Sikán — a woman “martyred by men to reclaim the sacred voice,” she explained in a 1993 interview. The symbolism of the fish, coveted as a sign of wealth, resonated deeply within the Abakuá mythos; men sought to venerate and appropriate its power, sacrificing the goddess Sikán and animal skin to make instruments that contained the sacred sound.

Through her exploration of these themes, Ayón illustrated a complete yet unseen imagery through the textures of the society’s symbolism, from her scenes of initiation rites to her salient portraits of Sikán.

Sikán, embodying the language and norms of a male-dominated society, serves as Ayón’s conduit to acknowledge the often overlooked but deeply felt presence of women within Cuban reality.

This dynamic relationship exposes the contradictions and complexities of collective memory. Sikán’s legend, in many respects, morphs into a cautionary tale, reinforcing the marginalization of women within the Abakuá tradition, reminiscent of Eve’s role in the biblical narrative of original sin. Ayón subverts the Abakuán Sikán myth by offering a critical, outsider perspective on a society and mythology dominated by men.

Her deliberate reinterpretation of this lore is acutely aware of the intersecting realities of history, aesthetics, culture, and language, inviting contemporary audiences to reevaluate their idealization of these narratives. Within the enigmatic folds of the Abakuá secret society of men and with the iconography of Catholicism, Ayon conveyed the complex composition of Cuba’s cultural and spiritual roots.

Strength and vulnerability in Ayón’s endeavours

Ayón’s dedication was not without burden, as her death by suicide at the age of 32 left a large void in the artistic landscape. Nevertheless, her work and talent continue to cast a profound and mysterious aura, enveloping Cuba with a cloud of spirit that remains cherished and protected.

Recognizing how an artist devotes attention to reality is a discipline that requires a great level of spirituality. In the enigmatic depths of the endeavours of artists such as Belkis Ayón’s lies a profound paradox of strength and vulnerability where the relentless pursuit of artistic expression converges with profound introspection, creating masked masterpieces that resonate with timeless power.

No comments to display.