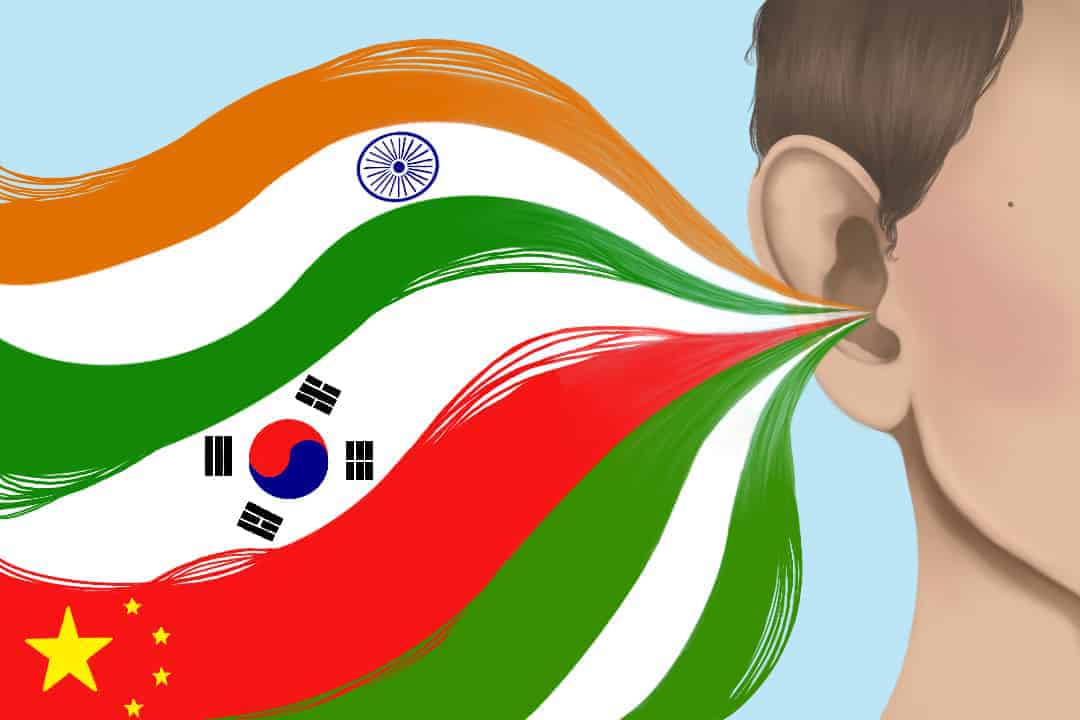

On January 25, U of T students and faculty participated in the lecture “Hearing Employability, Hearing Race” delivered by Vijay Ramjattan. The Department of Language Studies organized the lecture as part of the series “Jackman Humanities Institute Annual Seminar on Multilingualism: Reflecting on a Global Reality through Time, Space, Mind and Text.”

The series began in September 2023 and will run until April, with seminars addressing multilingualism in various fields of study and from differing viewpoints.

Ramjattan’s talk drew on his 2022 study, “International students and their raciolinguistic sensemaking of aural employability in Canadian universities.” He argued that the expectation that international students “sound Canadian” risks naturalizing racism. He also examined the narratives around which students make sense of these expectations around linguistic employability.

How accents become racialized

Ramjattan shared his experience growing up in Canada with a Canadian accent but explained that his accent is often heard as “non-Canadian” due to his racialization. Hearing “race” in the way someone talks, Ramjattan argued, is not a neutral or apolitical phenomenon — rather, it is influenced by social relations.

Most importantly, Ramjattan said, this process includes the power of colonial histories, white settlers, and the “myth of multiculturalism,” which serve to mask this power. Thus, an international student may be perceived as less capable of communication or less employable if their accent is not perceived as “white.” Because “employability” is a vague concept, international students are left concerned about how they should sound to be deemed employable.

Ramjattan describes this process as “raciolinguistic sensemaking” — an intertwined process of race and language that serves to make racist perceptions seem natural. In other words, Ramjattan explained, the process “deems the linguistic repertoires of racially minoritized communities as inherently deficient no matter if they match those of privileged white people.” For many international students, Ramjattan argued, this process can start while they are in university.

Emphasizing that the process is structural and ideological rather than specifically targeting a person or specific groups of people, Ramjattan said, “Raciolinguistic sensemaking was facilitated by the students’ everyday experience on their respective campuses.”

Sounding ‘Canadian’

In interviews with international students,. Ramjattan recounted that he observed two seemingly contradictory narratives on what “sounding Canadian” means to them: either the speaker mimics “white” accents, or they retain their native accent due to Canada’s supposed value of multiculturalism.

One student described being hired over a friend with an identical resume and skillset, the only difference being that this friend’s look and pronunciation were “more Persian.” Another talked of being told to get rid of their accents in a panel discussion about job-searching.

However, one student noted that the diversity of their university and the fact that their professor had a strong accent inspired them not to view their accent as a problem and to speak freely. Another shared that their faculty explained how students need not change their accents and that there are different ways to pronounce words in different countries.

Ramjattan remarked that while the narrative around multiculturalism and diversity may be salient in certain contexts, given the overall environment of the Canadian university and especially the job market, this narrative can be naïve or overly optimistic. The support of multiculturalism in Canada is essentially a myth, he said, due to the continued existence of systems of oppression that maintain white settler power.

He listed several other problematic examples of raciolinguistic sensemaking, such as the predatory nature of the “accent reduction” industry or bias in recruitment due to language perception.

To counter these effects, Ramjattan proposed “listening counter-pedagogies,” which are practices of teaching how to listen and approaches to communication that train both the listener and the speaker rather than placing the burden of “fixing” accents entirely on the speakers. He also emphasized the importance of addressing peoples’ accents and language use in anti-oppression policies and believes that these recommendations should be made in the wider labour market, not just at universities and niche workplaces.

No comments to display.