First, a disclaimer: the following isn’t meant to dissuade anyone from their faith, belief in a higher power, or optimistic nihilism. In fact, more power to you for walking through life’s trials by fire unscathed and stronger for it — I’m sure, one day, I’ll come out the other end too.

I have a fickle relationship with faith. My parents are Hindu by ancestry and choice, whereas I tend to identify as Hindu by ancestry, agnostic by choice, and a convert to any God who’ll take me by exam season.

I won’t go into extensive detail about why I walked off the path to salvation, ending reincarnation, or whatever else. Put simply, I’m a humanist at heart — I believe that I can satisfy my emotional and spiritual needs and follow an ethical life without God or religion — and am determined to stand by my own moral compass.

Nor will I go into how I walk the line between existentialism, nihilism, and absurdism — because I don’t. Every day, at random, I trip and fall — but never settle — into any one of the three philosophies about our life, death, purpose, or rather the lack thereof.

Instead, what I would like to divulge here is my love for the mythos and my unwavering love for my fellow women, mortal and immortal.

My love for Hindu stories was instilled by my parents, explored through Indian classical music, remembered during the excruciating wait for Uncle Rick’s The House of Hades, and like any Gen Z kid when the adults ran out of answers to our unending questions, reignited on the internet. I also grew up adoring the Hindu goddess Durga — a principal form of Shakti, the divine female energy; the protective mother of the universe; and a badass warrior — and I wish to embody her energy, forever and always.

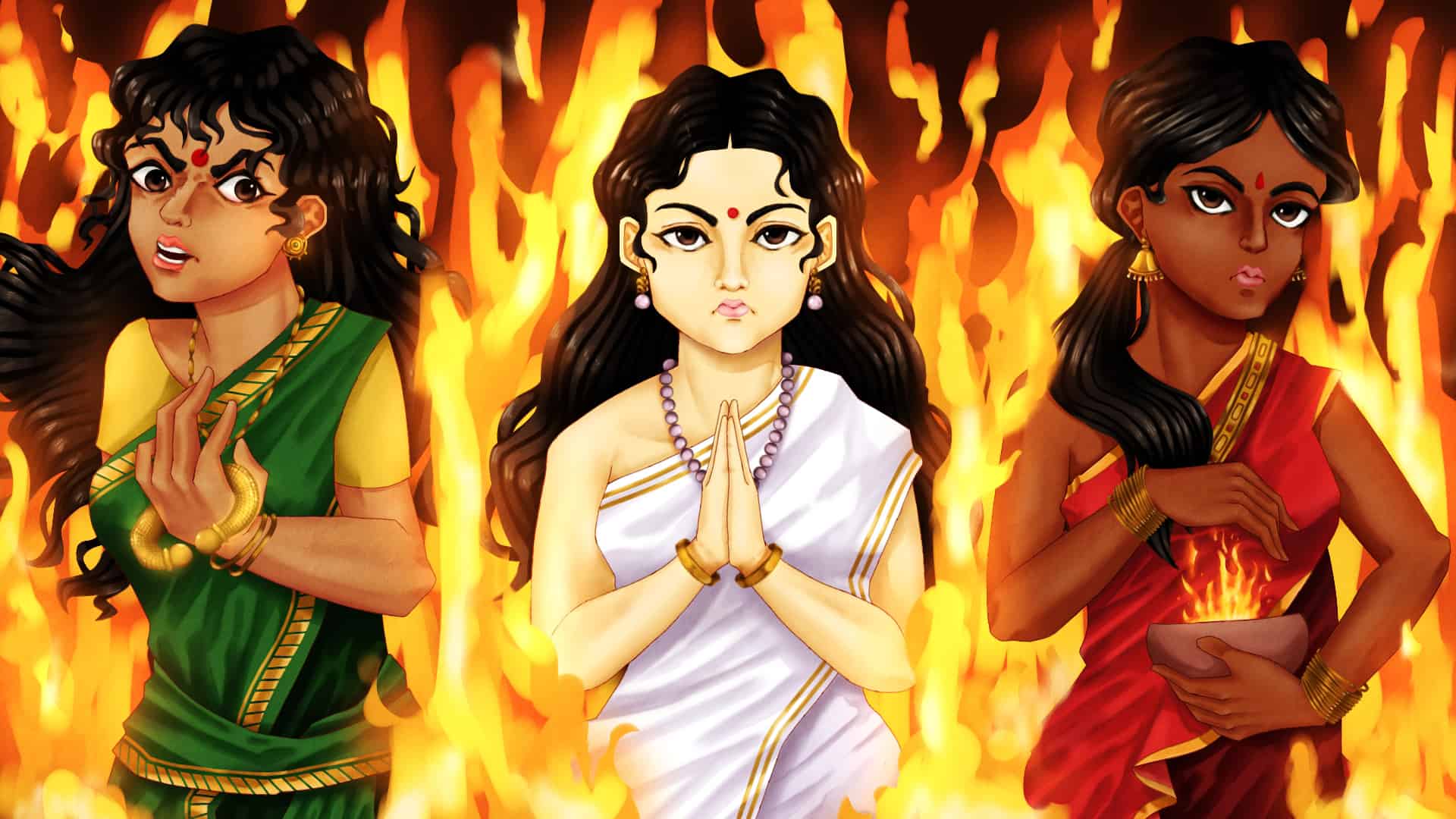

Aside from Durga, three other female figures also occupy my mind: Ramayana’s Sita, Mahabharata’s Draupadi, and Silappathikaram’s Kannagi. These women share three qualities besides being one of, if not the defining protagonists of different Hindu epics. One, they are strong women who endure tough ordeals and refuse to be beaten down. Two, they are women whose ‘purity’ is considered of the utmost importance — but, then again, what woman doesn’t have that in common? Three, oddly enough, they each share a story with Agni, the god of fire.

These women undergo unspeakable trials that involve large amounts of suffering, and their stories eerily echo how I think women are treated in society today.

Fire as creator, destroyer, messenger, and watcher

Fire is a ubiquitous part of anyone’s story — not just those of Sita, Draupadi, and Kannagi, whom we’ll get to soon.

Fire is a natural element of the Earth and one of humankind’s first discoveries. From time immemorial, we humans have been in awe of fire: it keeps the world bright, our food easy on the stomach, and us and our loved ones warm. Simultaneously, we’re terrified of it: painful to endure and sometimes deadly, fires can be weaponized against us, be it by mother nature or fellow humans.

Hence, it follows that Agni has a central role in Hinduism. Agni is often depicted in a deep shade of red with two faces — suggesting both his destructive and generous qualities — riding on a ram and wielding the fiery Agneyastra. And while considered the creator of the fire within the sun and stars, and the heat required for digestion, his humble abode is within wood, among humanity. As fire can be reborn with the friction of two sticks and maintained as long as there’s a steady supply of oxygen, he remains forever young yet immortal.

He’s also the courier between the human and celestial realms. From temple altars to homely shrines, lamps are lit from dawn to dusk in service of the Gods, to whom our prayers and from whom our boons Agni carries. In yagnas and pujas — rituals of fire — his seven tongues are said to consume sacrificial offerings, and the smoke trails signify their path to the gods above. In Hinduism, when people die, their bodies are cremated so that — according to some tales, at least — Agni guides their souls to their rightful destination in the cosmic order.

But to me, his most interesting and markedly different role from other mythological guardians of fire is that of the witness. As fire burns in every corner of the world, so does Agni, ever-watching the triumphs and tribulations of humanity. Agni is considered the primary witness for Hindu marriages, as a couple completes their seven vows to each other and the corresponding seven circles around the sacred fire. Because Agni bears witness to all, he’s also considered the best at discerning truth from lies. As such, fire is not only a creator, destroyer, messenger, and watcher, but also a judge.

Agnipariksha is the age-old practice of making someone walk through fire — or a proximate — with the idea that an unscathed success would indicate truthfulness and purity. It’s horrifying, and yet, the idea and execution of a ‘trial by fire’ isn’t unique to Hinduism, as the term originated from medieval practices. One of the most famous instances is that of Emma of Normandy in mid-eleventh century England, who twice widowed was accused of adultery with the Bishop of Winchester and required to walk across red-hot ploughshares to prove her innocence.

Furthermore, while something like ‘vibhuti,’ the sacred ash made of burnt dried wood or burnt cow dung, is applied across the forehead only among devotees of Lord Shiva — the destroyer of worlds and companion of Shakti — burning incense is also a common practice in Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity. Given that fire can eliminate filth and kill bacteria, it’s fitting that fire is seen as the remover of sin and revealer of truth.

So, Agni is a creator, destroyer, messenger, watcher, adjudicator, and purifier — but what does he have to do with Sita, Draupadi, and Kannagi? These women’s stories take place across the Indian subcontinent and across different times, yet Agni plays a crucial role in each one of them.

Sita in Ramayana

If you’ve ever celebrated Diwali — the festival of lights — with some Hindu friends, you probably have heard of the Ramayana. The epic, known in Sanskrit as “Rama’s journey,” centres around Rama and Sita: their upbringing, marriage, her abduction by the King of Lanka Ravana, Rama and his crew’s defeat of Ravana, and their return to the Kingdom of Ayodhya, where they are coronated as king and queen. The lamps lit by Hindus on Diwali symbolize the triumph of good over evil.

In the Ramayana, Sita is the incarnation of Lakshmi — the Hindu goddess of good fortune, wealth, and beauty. She’s also considered the daughter of Mother Earth, as she was found as a baby in a furrow that Janaka — the king of Mithila — was plowing, who then adopted and raised her as a princess. She married Rama, the prince and soon king of Ayodhya and the incarnation of Lord Vishnu, the maintainer of the worlds — thus her divine companion.

Agni crucially appears in the Ramayana after Sita’s rescue and the crew’s return to Ayodhya. When they return, Rama hears concerns among his citizens about Sita’s chastity, and Sita willingly performs an agnipariksha to prove herself to the kingdom.

The details behind the agnipariksha vary by the epic’s retellings across the Indian subcontinent. In one version, it is said Sita is being asked to prove herself to her citizens — but not Rama, as he knows her loyalty is on a cosmic level — primarily so that her husband can rule as a righteous and respected king. In another version, Rama also doubts her chastity, and Sita enters the burning pyre of her own accord to prove her faithfulness.

In a later addition to the original, Ravana is said to have abducted Maya Sita, an illusionary duplicate, while Sita was in the refuge of Agni. Through the agnipariksha, the real Sita switches with Maya Sita and returns. In this version, Rama is in on the plan while the citizens rejoice their queen is pure.

In yet another version, however, despite Sita being untouched by the fire, people continue to doubt, so Sita leaves for the forest. She returns years later with her and Rama’s grown-up sons, only to be asked to prove her chastity once more. Knowing that she’s done enough, Sita asks Mother Earth to open up and take her back — and Earth complies, swallowing her up whole.

Draupadi in Mahabharata

You may have heard of the Mahabharata through Oppenheimer’s famous misquote (“Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds”) from the Bhagavad Gita — a scripture from the epic detailing a lengthy conversation between Krishna, another of Vishnu’s incarnations, and Arjuna, one of the five Pandava brothers central to the epic.

The Mahabharata, the Sanskrit roughly translating to “the great epic of the Bharata dynasty,” centres around the Pandava brothers: their growing up; exile by their cousins, the Kauravas; and the war between the Pandavas and Kauravas.

There are many reasons this war broke out, but chief among them is Draupadi. When Drupada, king of Panchala, performs a yajna asking for a weapon to destroy the Bharata dynasty — the Pandavas and Kauravas — Draupadi is born as a fully-formed young woman from the sacrificial fire. Through a series of intentional and unintentional acts by the many characters in the epic, Draupadi marries all five Pandava brothers, further setting the stage for the oncoming war.

In all fairness, Draupadi herself didn’t intend to be a catalyst for the war. A pivotal moment in the war occurs when the eldest Pandava brother, Yudhishtir, bets his freedom in a slanted game of dice — and loses. When Saguni, the cunning maternal uncle of the Kauravas, reminds Yudhishtir that he still has Draupadi, Yudhishtir puts her at stake and loses her as well.

Draupadi is soon dragged by the hair into the court, and one of the Kauravas proposes that she is unchaste for being married to five men and orders that she be disrobed ‘like a prostitute.’ In the Ramayana, this is considered incorrect because her role as a common wife is seen as a private affair; she was given a boon in a previous life to marry five Bharata princes, each begotten by a god; and more importantly, as she was born from fire and thereby a child of Agni, Draupadi is the epitome of purity. Narrative aside, there are other issues with this comparison: it should be obvious that sex workers should, regardless of what you think of their occupation, have basic respect and autonomy.

Thankfully, her disrobing is stopped by the powers above — but not quickly enough as her humiliation fuels her righteous anger that her husbands would have to act on. Each of the younger four brothers takes an oath of vengeance against the various people who took part in her humiliation, which they later fulfill during the war.

Kannagi in Silappathikaram

The Silappathikaram may not be a well-known Hindu epic, but it’s considered one of the five great epics of Tamil literature. Silappathikaram in Tamil roughly translates to “the story of the anklet.” The anklet in question belongs to Kannagi, who has a special place in my heart; my dad affectionately calls me his “Kannagi Amman,” as she’s considered my family’s kuladeivam — roughly meaning “family god,” similar to a guardian angel of sorts, in Tamil. My parents and their ancestors lived near and daily visited one of her temples in Sri Lanka, and so, though I am not religious, hearing the name fills me with pride and reverence for my roots.

The epic starts with Kannagi newly married to Kovalan, absolutely in love and bliss in a flourishing seaport city in the Chola kingdom in what is now known as southern India. However, Kovalan meets and falls for a courtesan and dancer named Madhavi and moves in with her. Though Kannagi is heartbroken, she unwaveringly waits as a chaste woman for her unfaithful husband to return. Soon enough, a misunderstanding between Kovalan and Madhavi leads him to return to Kannagi, who takes him back despite the betrayal.

After having spent all his money on Madhavi, Kovalan is penniless — yet Kannagi encourages him to rebuild their life. They move to Madurai, the capital of the Pandya kingdom, where she gives him one of her jewelled anklets to sell. Then, in an unfortunate turn of events, Kovalan, framed by a merchant, is brought before the Pandya king whose queen’s anklets had been stolen and is immediately executed. Once she hears of this, Kannagi storms into the court and proves his innocence by breaking open her remaining jewelled anklet, revealing rubies instead of pearls. The king, mournful of his mistake, falls to the ground and dies suddenly, the queen soon following after him.

Still, in a fit of rage and grief, Kannagi tears her breast off and flings it, cursing the city of Madurai. She demands Agni to burn the city, permitting only the good to escape: a large-scale trial by fire. And so Madurai is burnt to the ground.

Placed on a pedestal, only to be burned down

By this point, you might be thinking: what the fuck?

These stories are tragic, the women undergoing severe hardship yet seemingly never achieving complete redemption. Sita, Draupadi, and Kannagi are epitomes of truth, strength, justice, and purity — but for what? It is precisely their sufferings — the reasons for which I don’t know — that keep my mind preoccupied.

Of course, it is easy to dismiss their tragedies when one knows that parables are meant to convey a tale of good versus evil and that Hindu epics, in particular, are meant to demonstrate ‘dharma’ — one’s duty, or the right way of living — and ‘karma’ — the effects of one’s actions that determine their next life.

The point of this article isn’t to wedge feminism between people and their faith. I know that, in these tales, the characters are simply mirrors that writers, or the Gods, hold up to humanity, to show us the paths we could, and should, be taking and their consequences. After all, Sita is ultimately Goddess Lakshmi playing a role; Draupadi is never fully human, born already a grown woman from fire as a weapon of destruction; and Kannagi becomes memorialized as Kannagi Amman, her chastity and valour worshipped by many, including my family. The three women are the perfect wives, and thus exemplary of the perfect woman.

Yet, the tragic heroine is a constant archetype in stories, past and present, which only begs the question: why are women in stories persistently made to suffer? In the Abrahamic religions, all evil stems from Eve’s eating of the forbidden fruit. No such similar story exists in Hinduism to my knowledge.

According to Aristotle, a tragic hero must have a hamartia — a fatal flaw or error, not necessarily a morally condemnable one — that leads to their ill fate. While I consider Sita, Draupadi, and Kannagi to be infallible, do they also have a hamartia? Is Sita’s fatal flaw her excessive trust, ‘allowing’ her to be kidnapped; Draupadi’s her sharp tongue, which angered the Kauravas and invoked their hatred; and Kannagi’s her forgiveness? Or, are they not even allowed to be less than perfect?

I should mention that none of this is to say that the men in these stories don’t suffer. The men — Rama and Ravana, the Pandavas and Kauravas, Kovalan and the Pandya king, and more — do suffer, but they more or less suffer directly or indirectly by their own and each other’s actions. How I see it, the women in these stories suffer at the hands of men — men they trust will give them at least basic respect and keep them safe — for no fault of their own.

Now, one might think there’s merit to these women’s trials; they’re at least not docile or passive, instead choosing to venture alone into the forest; single-handedly raise children; wage war; or burn an entire city to crisps in righteous indignation — but it is still unfair that they had to be so strong in the first place. Though Sita might’ve been the only one to go through a literal trial by fire, Draupadi and Kannagi, too, go through their own metaphorical ones.

When I think about it, nearly every single woman I’ve adored and cherished in my life — and this probably extends to every woman in the history of humanity — has been prodded, questioned, and tested, their value apparently never inherent to themselves but given, and just as easily taken away, by others. As women, we’re placed on the highest pedestals, seen as precious vessels of purity, until just one blemish taints our surface — after which we’re burned down to ashes and a new pedestal is built for the next unsuspecting woman. Sooner or later, we’re not young enough, naive enough, loyal enough, patient enough, or strong enough — good enough — for the patriarchy.

And having grown up religious, I can’t help but ask: what mistakes are okay? What is my supposed dharma, and is it different from that of men? Why is a woman’s chastity so important? Is my existence as a woman, marked by suffering according to one too many writers, karma for lives I don’t remember? Or are these stories simply highlighting the unfairness women endure from the men around them? Are these stories actually feminist?

When my mother lights the lamps and prays every morning at home — the place where seemingly only women are relegated to do so while men predominantly run the temples — should I join her? When I do join her, I watch the flickering flame and am reminded of Agni: in my story, does he play witness, protector, or male saviour? Or does he even care?

Often, I fear I am fated to end up like Sita, Draupadi, or Kannagi — my morality and intelligence tried, my body and self capitalized on without my will, or slowly made mad until I explode, incinerating everything I touch.

Alternatively, attaining perfection — impossible for any human but somehow made even more so for every woman — may just lead me to give up entirely. It’s a more liberating prospect but still shameful with my conditioning. I have to remind myself: while I aim to embody Durga, I’m only mortal and I can’t triumph over evil all the time, so I’ll make mistakes, and that’s okay.

Do I hope that Agni, in some form, helps me walk through my trials of fire? Yes: as I’ve said my faith, or lack thereof, is the opposite of resolute.

But more so, do I hope that I can tame the flames, stoked by the women who came before me, fictional or real, so I can direct them to the patriarchy and set it alight? Absolutely.