U of T’s Art Museum, located in King’s College Circle, is now showing the work of Caroline Monnet, a prominent Anishnaabe and French multidisciplinary artist. “Pizandawatc/The One Who Listens/Celui qui écoute” is her first solo exhibit in Toronto. It honours her great-grandmother, Mani Pizandawatc, who was the first in Monnet’s family to have her territory divided into reserves.

According to Monnet, Pizandawatc is derived from her maternal family’s traditional name before religious affiliates changed surnames in their First Nation reserve of Kitigan Zibi — an assimilation act by the Canadian government that used forced European renaming to disrupt Indigenous naming practices.

Mona Filip, the exhibition’s curator, shared that Monnet’s works detail the profound relationship between the resources her ancestors used to create and symbolize their culture, and modern ways of conveying Indigenous culture. Her work interrogates the way natural resources like wood are used today for mass production compared to before colonial disruption.

According to Filip, Monnet wanted this exhibit to be a “love letter to the land.” Her work goes beyond reproducing traditional motifs and mediums such as illustrations or paintings; instead, she develops them into the present and creates new motifs that sometimes remind viewers of QR codes, computer circuitry, and other modern technology. In doing so, Monnet creates continuity and explores how Indigenous culture manifests in the contemporary world.

Entering the Art Museum as a viewer, Monnet’s pieces captivate you with materials so familiar, yet reinvented: Monnet’s artistic prowess shines through a variety of mediums, including wood sculptures, textile creations, masonry, metalwork, immersive video experiences, and reworking of industrial materials. For example, Monnet recorded Anishinaabemowin phrases into layered native and industrial wood to reclaim the language and its connection to the land. Monnet breathes life into the wood, evoking a sense of deep respect for her Indigenous heritage while embracing a vision of resilience and storytelling.

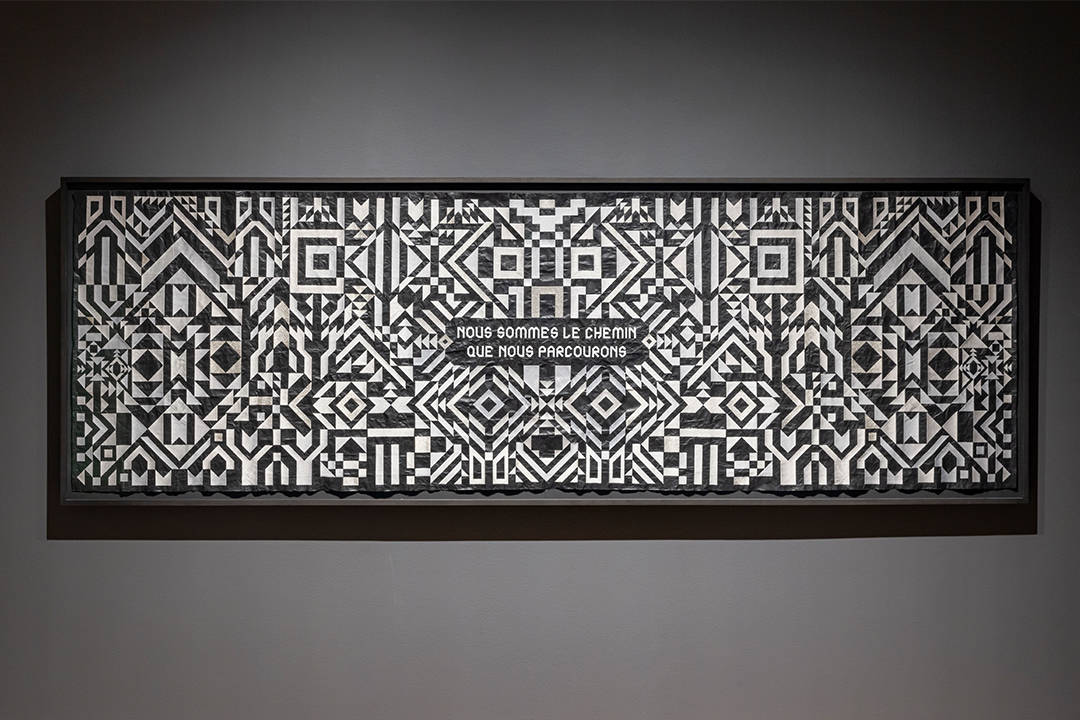

Monnet’s collaborative piece “Nous sommes le chemin que parcourons/ We are the path we travel” features the handiwork of embroidery artist Amélie Dionoski. The quote is from Serge Bouchard, and the frame was created by Martin Schop’s Encadrement. This collaborative piece was inspired by a tapestry Monnet previously created for an exhibition at La Galerie du Nouvel-Ontario that celebrates the same geometric and Indigenous motifs.

The materials used in Monnet’s pieces are central to lifestyle and traditional craftsmanship within Anishinaabe communities and cultures. Monnet’s work highlights how wood as a resource was readily available before colonial exploitation. It features bronze as the first copper-based alloy the Anishinaabeg used.

The materials not only pay homage to Indigenous traditions of craftsmanship but also serve as a metaphor for Indigenous artisans’ resilience and endurance. “Ikwe origami (Portage de la Femme)” is made out of maple wood and is carved to represent the sound waves of Anishinaabemowin voices. By solidifying language into wood, Monnet highlights the important relationship between the land and Elders, as its knowledge keepers, that remains even after cultural genocide.

Monnet’s revitalization of woodworking and metalworking shows how traditional Indigenous identity and craft can re-emerge in new ways. The patterns Monnet creates draw inspiration from the Anishnaabe art form of birchbark biting.

Monnet’s piece “Canopy” reflects her continued examination of industrial construction supplies. “Canopy” is made of asphalt shingles and oriented strand board with ornamental perforations throughout creating a pattern that holds connections that will remain indefinitely. She re-envisions how connections in the community are made and the value they hold, and she makes permanent a constellation of these relationships she has made which makes viewers reflect on how their own circles emerge.

Monnet’s piece “Canopy” reflects her continued examination of industrial construction supplies. “Canopy” is made of asphalt shingles and oriented strand board with ornamental perforations throughout creating a pattern that holds connections that will remain indefinitely. She re-envisions how connections in the community are made and the value they hold, and she makes permanent a constellation of these relationships she has made which makes viewers reflect on how their own circles emerge.

Her textile works incorporate traditional Anishnaabe motifs and symbols reimagined through a modern lens, such as her tapestry work “Akwìnowag (Flock)”: strands of plastic Tyvek sheets are sewn individually to form the eye of a tornado. Monnet shares that she usually starts creating these designs with squares, to create a maze of different patterns.

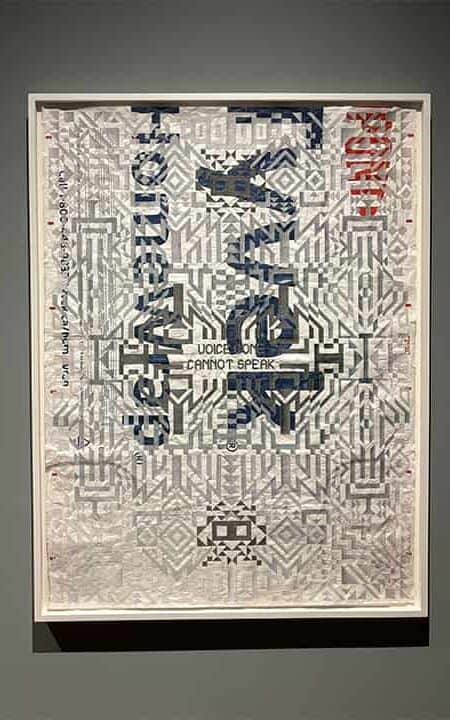

Another piece, “Voice Gone Cannot Speak,” confronts the loss of Indigenous languages due to colonialism. Through bold colours, intricate patterns, and meticulous attention to detail, Monnet’s textile creations offer a sense of cultural pride and mourn what was lost. Her other textile works hold phrases such as “No Church in the Wild,” and “Wolves Don’t Play By The Rules.” These phrases offer a vision of cultural renewal that demonstrates Indigenous heritage beyond victimhood.

Barbara Fischer, executive director of the Art Museum, believes that this exhibition is important in disrupting colonial history and its control of the land. In programming this exhibit, the Art Museum engaged with the Office of Indigenous Initiatives and a number of faculty, such as Mikinaak Migwans, an Assistant Professor of Indigenous Contemporary Art in the Department of Art History and a curator at the Art Museum. The exhibition brings about memory, history, and questions of colonial disruption, but also encourages viewers to challenge colonial frameworks and reclaim power through art.

In an interview with The Varsity, Monnet said, “It’s the message that dictates the medium that I choose.” Monnet expresses that she doesn’t want her work to just be regarded as beautiful: “I would like it to also be effective and contribute something positive to society.” This is why she incorporates social justice topics and applies her background in sociology to her pieces.

In 2017, U of T published the Wecheehetowin recommendations, the final report of the Steering Committee for the University of Toronto’s Response to the Truth and Reconciliation Committee of Canada. Among the recommendations in the report is a call for more Indigenous artwork that reflects Indigenous peoples’ contributions to Canadian culture and society. Monnet’s works answer this call and are an important step in promoting Indigenous art at U of T.

The exhibit is on until March 23 and admission is free to all.

No comments to display.