Content warning: This article mentions gun violence.

American academic and author Grace L. Dillon, of Anishinaabe and European descent, coined the term “Indigenous futurism” to platform Indigenous science fiction, which has been overlooked in the face of Western technoculturalism. Indigenous futurism describes art and literature that is centred around Indigenous scientific literacy and intellectualism, and Dillon advocates for this literature to reclaim its place in the sci-fi genre.

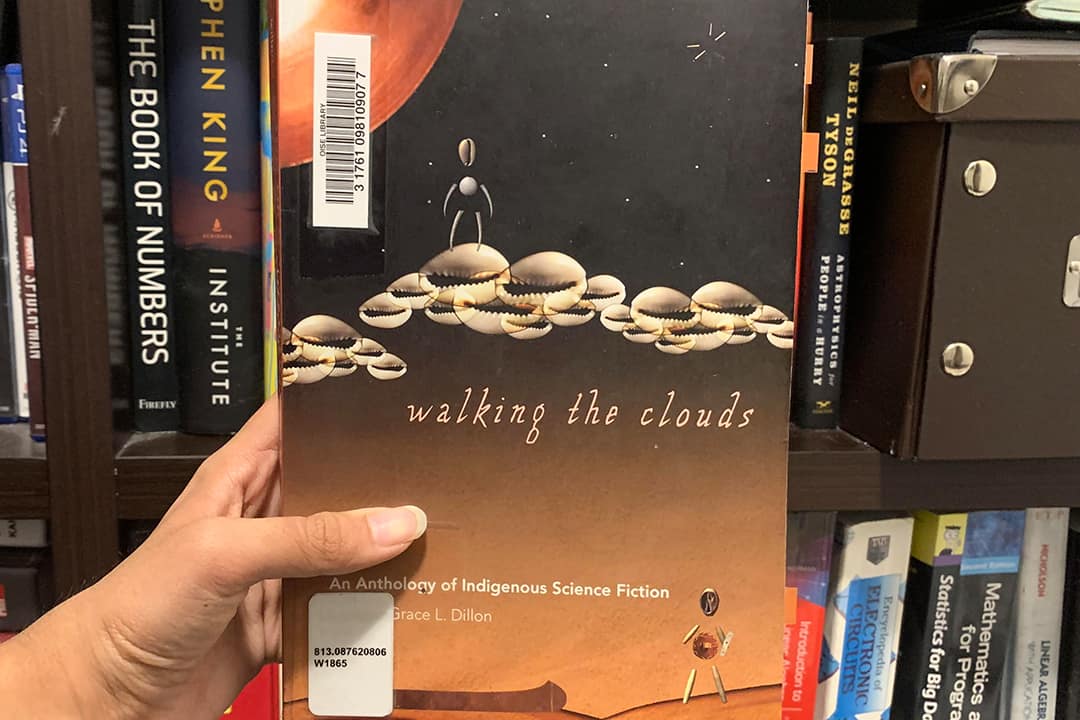

Walking the Clouds is a 2012 anthology of Indigenous science fiction that Dillon edited. It contains short story excerpts and prose from writers that confront postmodern, postcolonial Indigenous experiences in a struggle for survival against colonization across terrains — “whether geopolitical, psychological, sexual, [or] otherwise,” as Dillon says in the introduction.

The book is divided into five themed bundles of stories: “Native Slipstream,” “Contact,” “Indigenous Science and Sustainability,” “Native Apocalypse,” and “Biskaabiiyang: Returning to Ourselves.” Each section offers a handful of excerpts from various writers, and I’ve picked three of these excerpts to spotlight below.

Flight by Sherman Alexie — from “Native Slipstream”

The section “Native Slipstream” looks at the fluidity of time, memory, and presence and the possibility of multiverses and time travel. The section’s main message is about bringing attention to the present and building a better future. Dillon describes the tone of the stories of this chapter as full of “sardonic humour” and “bittersweet hope.”

A Spokane/Coeur d’Alene poet and novelist, Sherman Alexie’s Flight takes off in the first-person narrative frame of Zits, an angsty teenager the author describes as being of Irish and Native American descent, who contemplates — and eventually rejects — participating in a killing spree at a bank in Seattle.

In an introduction to the excerpt of Flight, Dillon suggests that Zits’ character has been put together as a “typifie[d] reservation youth today” to help him move beyond the “self-loathing of internal colonization” that “reservation youth” may experience.

Zits is an orphaned teenager who has run away from foster homes several times since his childhood. When his narrative frame shifts from the present — the bank — to glimpses from his childhood, we relive his abuse, trauma, and struggles with forming his identity.

Eventually, he is taken in by a police officer to whom he confesses about guns he had kept for the killing spree, followed by an interrogation which gives him a chance at reflection. When he is taken in by two police sergeants, Dillon highlights the shift of the narrative frame in reflecting Zits’ own struggles with his identity.

This excerpt masterfully displays an intimate understanding of Zit’s character, and motive — or lack thereof — in brief, seamless transitions of flashes from his childhood. Stepping into Zits’ body and having his childhood trauma flash before his eyes adds a hyperreal touch to the moments he spent contemplating at the bank. He does not actively assert or initiate a memory — rather, he seems to live it and become the person he was growing up at various stages of his orphaned childhood through foster homes.

Men on the Moon by Simon Ortiz — from “Contact”

Whether physical contact through discovery and exploration across new worlds and terrains or verbal contact by sharing a language, through “Contact,” Dillon wishes to address that Indigenous writers’ science fiction might be curated, ironically, to challenge and “taunt” their readers’ positions regarding the condition of the Indigenous diaspora.

Dillon says that Simon Ortiz’s Men on the Moon subtly challenges the notion of “techno-primitivism” that is associated with a disregard for Indigenous intellectualism.

In this excerpt, Faustin, an Indigenous Elder, dreams of a machine monster on the moon in the wake of watching the 1969 moon landing on a newly set-up television. Through Faustin’s experiences, Ortiz weaves an ironic, metaphorical story by juxtaposing the image of the astronauts’ quest for knowledge with Faustin’s dream of a mechanical monster on the moon.

When Faustin is surprised and wonders why the “Mericanos” must go to the moon, he asks his grandson if the astronauts are searching for something on the moon, to which he is told that they seek knowledge. He muses to himself, wondering if “men had run out of places to look for knowledge on the earth.”

This story looks at Faustin’s experiences as a person unfamiliar with television and the English language. He relies on his grandson’s translations and explanations about the moon mission. He is genuinely surprised at the fact that the astronauts would go to such lengths in search of answers about the beginning of creation and the search for “the tiniest bit of life” on other planets.

Ortiz, who is from Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, engages in an experience that I believe many immigrants and non-English speakers would find relatable. His juxtaposition of Western space conquest with Faustin’s dream of an invading machine monster reflects the narratives of colonialism and contact — as it relates to the larger theme of the section — through discovery and annihilation.

Dillon explains that Ortiz’s story explores catastrophic change from an Indigenous perspective, rather than through wonder and the glorification of exploration and annihilation that are typical in mainstream science fiction.

The Moons of Palmares by Zainab Amadahy — from “Native Apocalypse”

“Native Apocalypse” refers to “the ruptures, the scares, and the trauma” as part of the larger collective healing process depicted in this anthology. In this section, we see themes of apocalypse, either as the build-up or in the aftermath, and the steps to revolution and recovery.

Activist and writer Zainab Amadahy — who is of mixed-race background, including African American, Cherokee, Seminole, Portuguese, Amish, and Pacific Islander — wrote a futuristic adventure story in a distant world. It touches on the politics and reality of a technologically superior colonizer culture exploiting the Palmerans — an Indigenous population in the world of Palmares — for their rich natural resources.

The excerpt begins after an earthquake, which results from heavy volcanic activity from the excess mining on Palmeres’ moons. This story has themes of neocolonialism and political independence as well as resistance, morality, and corruption in an intergalactic setting. I found this story quite powerful, as it jumps right into the characters leading up to a revolution in an apocalyptic setting.

The many faces of colonialism

In my experience, most science fiction pertains to some kind of futuristic world with advanced biomedical technologies, infrastructures, and vehicles, all topped with a beautiful message of equality and accessibility for all. Sometimes, these media texts also come with complex, sometimes dark, or disturbing underlying themes of a dystopia looming behind the superficial clouds of silver lining.

In the cases of all three excerpts, we are presented with the themes of space, time, and technology seen in typical mainstream science fiction through the perspective of Indigenous characters. Occasionally we also see themes of the many explicit and implicit faces of colonizing powers in futuristic settings — whether as huge corporations and political entities, technologically powerful space travellers, or in the deliberate mediation of contact and understanding through language.

Colonization, whether through advanced technology or cultural and linguistic dominance, has many faces — and remains the same in spirit.

No comments to display.