A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers is one of those novels that you settle in with after a long day, hot cup of tea in hand. It follows a monk, Sibling Dex, who lives in a singular city on the lone continent of a colonized alien moon. Half of the continent is composed of the city and small satellite villages, and the other half is left to wilderness. The ocean remains mostly unexplored.

This world is a comfortable one — everyone’s needs are provided for, most people live easy lives, and humanity has escaped the shadow of the “Factory Age” of robots. However, this utopia was only achieved because hundreds of years prior, robots developed consciousness and decided to leave human society for the wilderness.

Unsatisfied with their life, Dex leaves their post at the monastery and chooses to wander from village to village instead, lending an ear to villagers’ woes while mixing them the perfect tea blend. Dex wakes each morning feeling like something is out of place, and they don’t know what they could possibly do to find their purpose in life. Then, Dex meets a robot: Splendid Speckled Mosscap. Mosscap follows Dex as they venture farther into the wilderness, asking one fundamental question: what do humans need?

In many robot-human tales, robots are programmed and mechanical, and they think numerically. Psalm shows us what might happen if robots were curious. Mosscap spends its days observing flora and fauna, feeling content wandering the continent instead of settling on one thing. At one point, Dex questions how Mosscap could be so fluid while made of machine parts, and Mosscap points out that the machine parts are “how [robots] function, not how [robots] perceive.” In this world, robots no longer only fulfill the purpose for which they are constructed, and so they must find their own.

Learning from the vampire squid that existing is enough

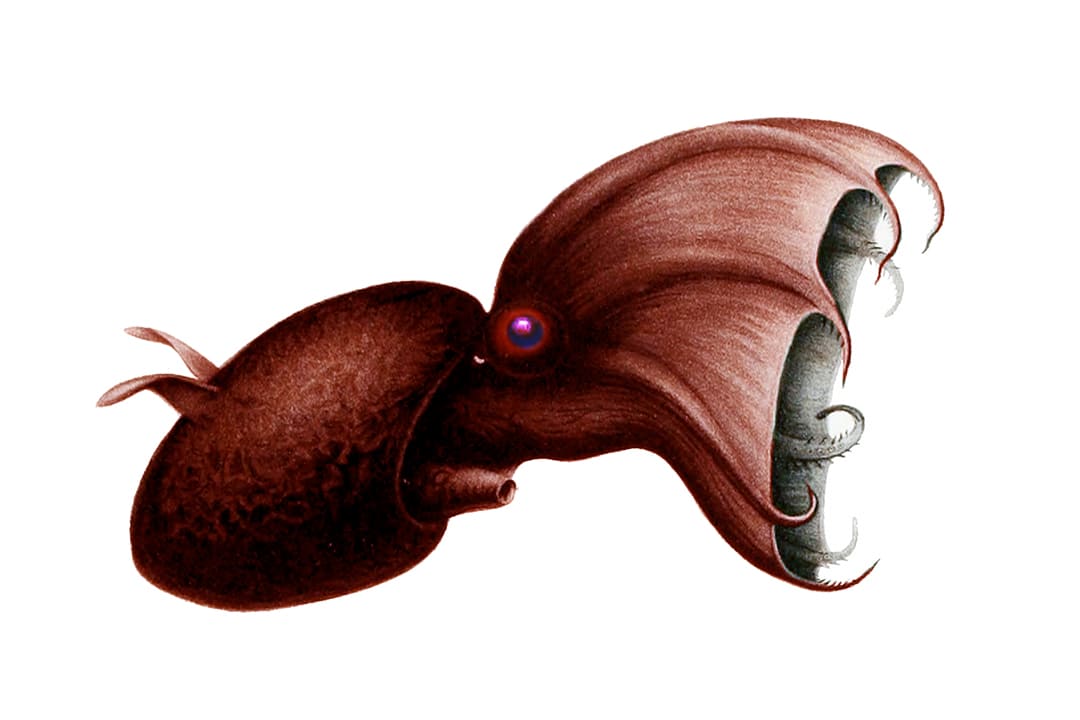

In Vampyroteuthis Infernalis, Vilém Flusser also explores the purpose of human existence, this time through one of the most mysterious animals of his time: Vampyroteuthis infernalis, or the vampire squid. The book greets us with speculation on the phylogenetics of the titular species, filled with ostensibly scientific information.

Yet there’s something strange about this book. Flusser blends scientific description with philosophy and fiction to create a chimera of a work, one that questions what it means to be human as much as it asks what it means to be a vampire squid. Although many of the scientific facts he presents are grounded in reality, his analysis of these facts extends into imagination, which is why I approached this book as science fiction.

Flusser was fascinated by the extreme environment in which vampire squids live. Vampire squids can survive under minimum oxygen levels at depths of between 600 to 1,200 metres in the ocean, leading them to develop several ingenious adaptive features. They don’t hunt prey but instead have filaments attached to their legs with mucus that picks up detritus from the ocean to consume.

With these scientific facts in hand, Flusser extends the environment alien to us into a philosophy of the vampire squid’s interaction with the world. To him, humans and vampire squids exist in different worlds — ours a “habitable surface” and the vampire squids’ a “habitable hole.”

Despite this, Flusser concludes, “Nevertheless, we can meet.” Vampire squids’ passive method of food consumption inspires Flusser, as he says that the animal “embraces the world with the intention of incorporating it.” From the squid’s behaviour, Flusser draws out a metaphor, implying that passively existing in the world is enough of an existence.

Flusser writes that “the encounter between the two Earths would be the absorption of the human Earth by the vampyroteuthian one.” What does it mean that Flusser thinks the “vampyroteuthian” way of life can overcome our own method of existence — one where we are driven to find purpose in what we do? Maybe, it is that humans aren’t so exceptional that we need a purpose in life to continue existing as we do.

Psalm and Vampyroteuthis on purpose

I arrived at Psalm and Vampyroteuthis during an opportune moment in my life. Everything was going right, yet I wondered: what if I had done things differently? What if I had tried harder to reach my goals when I was younger?

For Flusser, these questions are both complex and silly. Our purpose can be to simply exist as beings. In Psalm, Mosscap quashes Dex’s yearning for purpose by pointing out that “[they’re] an animal. And animals have no purpose. Nothing has a purpose. The world simply is.”

My struggle with science started with a love for science fiction. When the impossible seems possible, real life is made small and bitter. I used to wonder how scientists could find value in the minutiae, spending years researching one mechanism of one reaction in a plant and feeling satisfied. We often place research into a larger picture, trying to rationalize each small project through its utility for our development as a species.

Science has a purpose — but did it start this way? Did the first person who observed a frog’s tympanum vibrating know that they were viewing a crucial part of the frog’s anatomy, or did they just enjoy the sound it produced? I will never know the answer to that question, but I do know that it is enough to simply accept the knowledge. It is enough to simply exist, to embrace the world as it is — like the vampire squid.

No comments to display.