Students of UofT Occupy for Palestine (O4P) have turned the King’s College Circle into the “People’s Circle for Palestine.” As discussions around the encampment at U of T grow, it’s important to understand why culture and art are crucial to protests, to the encampment, and to raising awareness about the humanitarian crisis in Palestine.

From the chants you hear in every protest to the ‘keffiyehs’ you see protestors wearing, each bears a significant meaning and relevance toward Palestinian culture and the protest.

Poetry’s influence on the Palestinian movement

Mahmoud Darwish and many Palestinian poets such as Refaat Alareer and Najwan Darwish, have been consistent pillars in the Palestinian movement, renowned for their work that deeply resonates with the minds, bodies, and souls of Palestinians.

Words, as in Darwish’s I Belong There, Alareer’s If I Must Die, and Darwish’s The Shelling Ended, have been in the hearts of Palestinians for many years, allowing them to deliver their truth to the rest of the world.

For Palestinians, poetry serves as “compensation for their lack of physical power” against Israeli occupation. It inspires people to take action, engage in protests, honour and remember significant events, and bear witness to the collective Palestinian struggle.

I personally witnessed the power of words and symbols at the U of T encampment on May 23.

Power behind words and symbols

Poetry holds great influence and resonance among pro-Palestinian advocates who are protesting. When their voices chant in unison, each verse and rhyme embodies deep historical truths in advocating for Palestinians’ liberation.

As one group of protesters chants “From the river to the sea” and another responds “Palestine will be free,” you would not be the first to wonder about the significance of these phrases for Palestine.

These chants represent Palestinians’ aspirations for freedom and self-determination throughout the historical land of Palestine. To Palestinians, the phrase “river to the sea” refers to Israel-occupied Palestine, as Palestine historically stretches from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. The part of the slogan, “Palestine will be free,” expresses the desire for equality and liberation from Israel’s occupation since 1967 in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The slogan gained prominence in the 1960s among Palestinians seeking independence from Israeli occupation.

Yousef Munayyer, Head of the Palestine/Israel Program at the Arab Center Washington DC, explains that Palestine supporters who use these chants are often wrongly perceived as inciting violence. Munayyer notes that Palestinians’ lack of fundamental rights and freedoms perpetuates deprivation of justice, equality, safety, and security: issues that the chants bring to light.

AIDA QAZI/THE VARSITY

With the chant, “No more hiding, no more fear! Genocide is crystal clear,” protestors exclaim to the world that we shouldn’t stay silent about the fact that a genocide is happening before our eyes. They urge world leaders to cease supporting these atrocities.

In March, Francesca Albanese, a United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Palestine, defined genocide under international law as actions aimed at eradicating a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. She asserted that Israel is committing three acts of genocide against Palestinians: causing severe physical or mental harm, imposing conditions meant to destroy the group physically, and implementing measures to hinder births.

She also described Gaza as at the apex of a “long-standing settler colonial process” aimed at erasing native Palestinians. Thus the protesters chant, “genocide is crystal clear.”

Importance of literary texts to the U of T campers

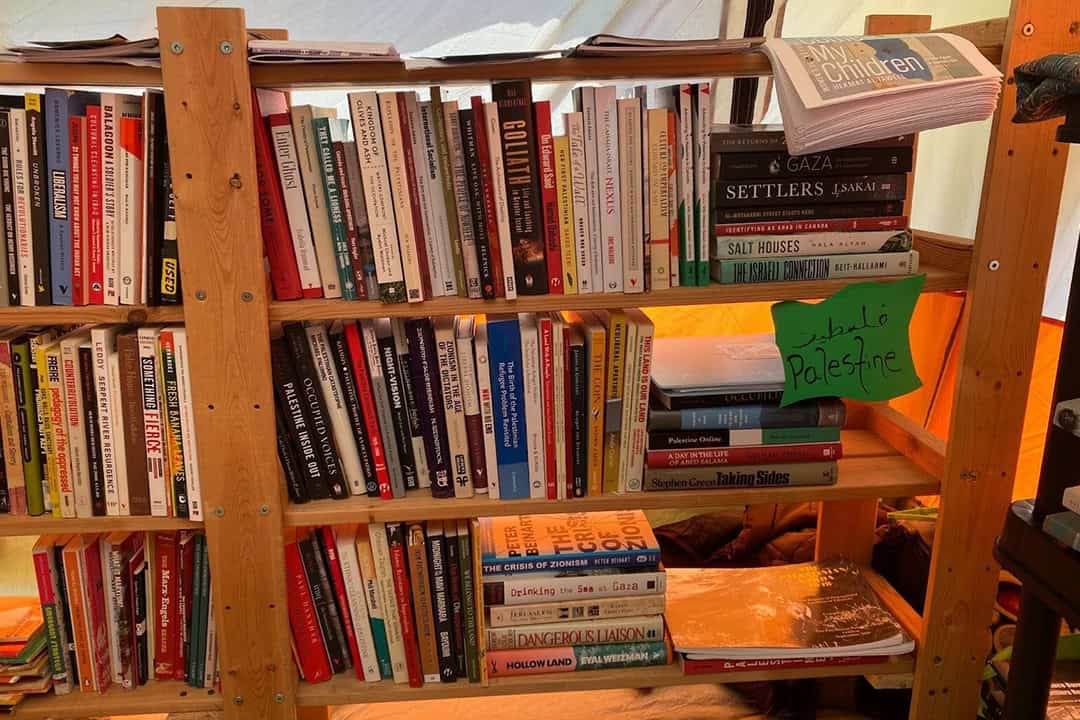

When asked about the role of literary texts in Palestinian protests, Erin Mackey, an O4P spokesperson and camper explained, “We have a whole library tent at the back called the Watermelon Coalition. It includes around 230 books, featuring Palestinian literature, Black literature, prayer books, and even colouring books for children.” She mentioned that campers organize reading circles where they read excerpts from various Palestinian scholars, poets, and authors, and learn about Palestinian history and traditions.

Another camper named Jocelyn — who requested her last name to be anonymous due to safety concerns — also shared her thoughts: “For me, it’s about Power Born of Dreams: My Story is Palestine by Mohammad Saba’aneh.” She explained that Saba’aneh, a Palestinian formerly imprisoned in an Israeli prison, created the graphic novel using a unique method of carving images and words into stamps, which resonated deeply with her. Through this art form, Saba’aneh recounts his story and those of other Palestinian families, making a profound connection between his experiences and his artistic expression.

AIDA QAZI/THE VARSITY

Cultural significance of the keffiyeh

Often worn at pro-Palestinian protests, the keffiyeh, in its various colours and styles, symbolizes solidarity with Palestinians. Whether worn on the head or shoulders, the traditional Middle Eastern headdress carries deep cultural significance.

Some say that the keffiyeh’s netted pattern symbolizes the Palestinian’s ties with the Mediterranean Sea. To many, it signifies abundance, grace, and freedom, but it also evokes the West Bank — many parts of which are designated as “closed military areas” by Israel — which restricts water access and deprives Palestinians of their connection to the sea.

For Palestinians, this sea wave pattern symbolizes resilience through 76 years of Israeli occupation, with its bold lines representing the historic trade routes that have shaped Palestinians’ diverse cultures.

Abdurraheem Desai, a U of T student camper, shared that the keffiyeh provides a quick and recognizable way to show support, despite the risk of harassment. Its traditional yet common design makes it an easy addition to one’s attire.

Desai mentioned that, “You become part of a larger group that is all joined with the same piece of cloth.”

AIDA QAZI/THE VARSITY

Building community through activism

Mackey reflected on the deeply transformative experience of being an ally and working for the Palestinian cause at U of T. She describes the campus as often isolating, but through this activism, she has found a sense of community and forged friendships that she believes will last a lifetime.

Engaging in collective activities like praying, singing, and painting has exposed students, faculty, staff, and the broader U of T community to a rich tapestry of cultures and faiths and united them in a shared mission to call on the university to disclose and divest from companies supplying the Israeli military.

AIDA QAZI/THE VARSITY

Viva Viva Palestina; Long Live Palestine

The fact that many people may not grasp the depth of various Palestinian chants during protests underscores the importance of expanding our knowledge to enable art to meaningfully intersect with daily activism.

While reflecting and reminding ourselves of Palestine yesterday, today, and onward — let me leave you with Darwish’s powerful words from “Silence For Gaza”:

“We let him triumph, then when we dried our lips of poems we saw that the enemy had finished building cities, forts and streets. We do injustice to Gaza when we turn it into a myth, because we will hate it when we discover that it is no more than a small poor city that resists.”