The “cool girl” novelist is here, she’s sad, emotional, and unapologetically herself. She’s also deeply hated. In the world of modern fiction, she’s the ultimate disrupter because she’s raw, real, and rewriting the rules of what it means to be a cool girl.

The rise of the “cool girl novelist”

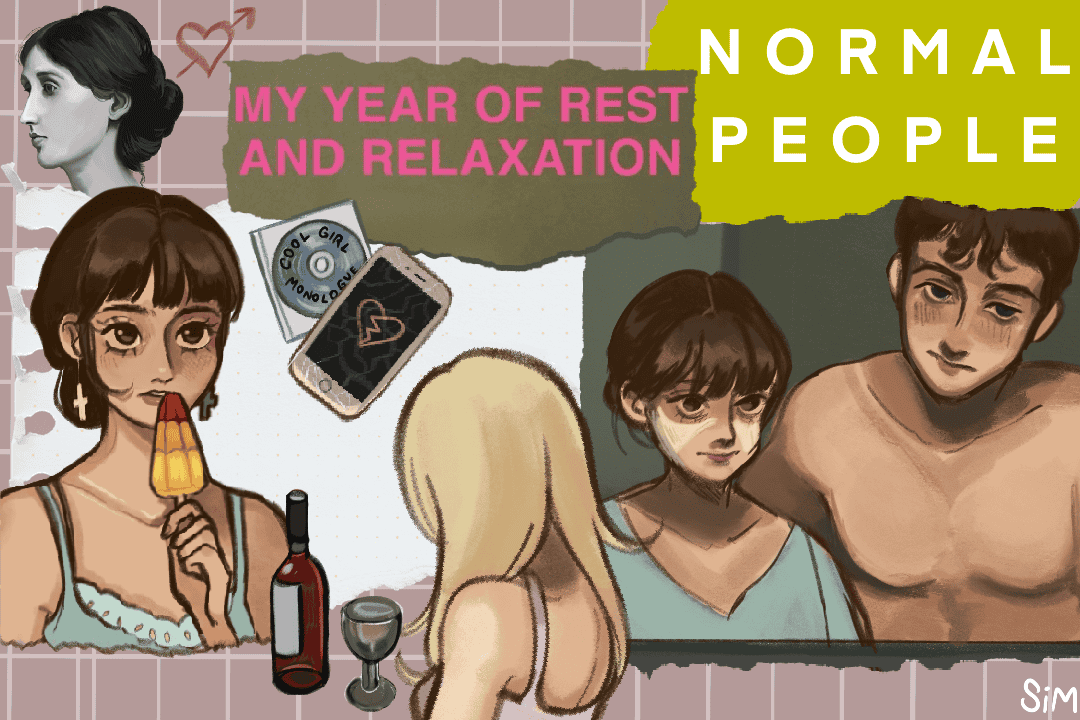

Sally Rooney stands at the forefront of this cool girl movement, with her novels like Normal People that, without brimming with emotion, cause tremendous discourse on every social media platform. But writers like Rooney don’t shy away from life’s messiness — they dive right in, offering a mirror to our own anxieties and desires. Their stories are intimate, their prose is sharp, and most importantly, their impact is undeniable. So, why do we despise them?

Charlotte Stroud, a columnist at The New Statesman, placed Rooney at the centre of the discourse when critiquing the cool girl novelist and “sad girl writers” phenomenon in “The curse of the cool girl novelist.” The piece lambasts these authors for the supposed triviality of their work, their angst, and self-absorption. Ironically, this article strikes me as a very cool girl in the sense of author Gillian Flynn — a woman talking about how awful other women are for constantly complaining.

The truth about cool, sad girl novels is that they are simply stories centring young modern-day women. The stories resonate with them as many young girls navigate messy, angsty lives, and may crave fiction that mirrors their reality: balancing intelligence with accessible prose.

The angst in these books is multifaceted. Sometimes, it is tinged with moral anxiety, a reflection of living in a politically charged society where everyone feels compelled to showcase their virtues on social media. Other times, it’s about beauty, exacerbated by social media culture, sexual trauma, economic anxiety, or a general sense of unease the protagonist herself doesn’t fully understand.

Authors like Ottessa Moshfegh, Raven Leilani, Elif Batuman, Carmen Maria Machado, and Mona Awad join Rooney in embracing the messiness of women’s existence. They offer readers a mirror to reflect their own anxieties and desires, making the angst of modern life feel both profound and relatable.

In her critique, Stroud can’t grasp why women authors today aren’t just “bucking up” and being more cheerful — and she lacks consideration that men could write this way, too. The absence of counterexamples by women writers implicitly suggests women write in a “bad” way while men write in a “good” way.

Stroud tries so hard to lump together a group of cool girl authors, all of whom are accused of using words to describe, introspect, and be women. I feel that Stroud is just listing a bunch of women they don’t like, pretending they form a meaningful category we should all be upset about. There’s no genuine connection between many of them, like grouping My Year of Rest and Relaxation author Moshfegh and Rooney, who have almost nothing in common.

Why cool girl novels hit different

These books are relatable because they reflect the feelings of many young people now, particularly women: depressed and alienated, having grown up through pandemic lockdowns, housing crises, and the craziness of social media. It’s no surprise that readers want characters who feel as empty as they do.

“Their depressed protagonists hardly speak at all,” Stroud writes — but who are “they?” Is it Marianne from Normal People who struggles with self-love and lack of worthiness? Is it the sleeping and internally dead unnamed protagonist from My Year of Rest and Relaxation, who ultimately discovers the beauty in being awake and alive?

But what I find makes the name-dropping in Stroud’s article further unexpected is that Rooney’s novels in particular are deeply optimistic. They argue that love, with its raw attachment and vulnerability, transforms into a system of mutual care, challenging the myth of individualism and highlighting our radical interdependence. Marianne would not have chosen herself without the security that Connell’s love provided. His love makes her see her own goodness, and somewhere along their relationship, Marianne stops viewing herself as despicable. For the first time, she feels confident enough to prioritize her happiness and discover her identity beyond her insecurities.

Rooney’s characters may seem aggressively mundane, living simple, unremarkable lives, but their stories and experiences are profoundly intriguing. They are indeed normal people who feel, love, and break the same way we do.

This ordinariness makes Rooney’s work relatable and deeply optimistic. Her books suggest that genuine human connection and love can lead to healing and growth. They argue that love is one of the few things in the world worth pursuing, although often marked by hatred and cruelty. This is a running theme of Rooney’s optimism and perspective in her novels: love doesn’t fix but rather heals.

The hate train for sad girl novelists needs a serious upgrade

The critique of so-called cool girl novelists seems to miss a crucial point: sad girls have a right to express their experiences through writing. While authors who are men — think of Ernest Hemingway and even J.D. Salinger — have long explored themes of depression and alienation, there’s now an uptick in women writers doing the same.

However, instead of being met with understanding, the cool girl novelists face mockery and derision. Stroud suggests that novels should entertain rather than instruct, dismissing the value of exploring the human condition through literature. I see this approach as reflecting a form of literary misogyny, using the perspectives of writers who are men to devalue the work of women authors.

By labelling women novelists as emotionally hysterical or preachy, Stroud diminishes their contributions to literature, as if Rooney and her contemporaries are simply whiny girls seeking validation. Her criticism directed at cool girl novelists reveals more about societal biases and expectations than it does about the quality of their writing.

So, let’s embrace the cool girl novelist for who she is — a powerful yet small addition to the modern literary landscape because, if we’re being brutally honest, she’s not even close to breaking the status quo or bringing in a new set of diversity. She’s just a sad girl.

No comments to display.