Treasure Fatile — a fourth-year art history and criminology student at UTM — is impressively quiet and controlled. This gentle aspect, revealed in her paintings as fierce introspectiveness, presents studies of “silent narratives” charged with expressions of joy, sorrow, resilience, and vulnerability.

Recently, at the exhibition Faces in Places, which culminated an eight-month residency at Visual Arts Mississauga, Fatile displayed her recent work alongside her fellow creative residents in the presence of friends, mentors, colleagues, and family. I attended the exhibition on June 1 and what I saw from Fatile moved me.

It is fitting that at an exhibition centering on “figures, faces and the human form,” Fatile displayed faces and bodies of women, muddied and aglow with their barely controlled inner turmoils and protruding traumas. These bodies were frozen in states of mystical and spiritual unrest, while the charged space between the rock of Black racial identity and the hard place of traditional African society depicted the form of womanhood.

Fatile’s overarching themes utilize patterns, textiles, and motifs from her Nigerian-Yoruba cultural heritage to interrogate what she describes as “the self in relation to different environments: deeply interested in how these factors intersect with manifestations of joy, belonging and loss.”

For Fatile, the face, the nonverbal, and the things unsaid reveal the human soul. In her painting Ọ̀rẹ́ Ìyàwó(Friends of the Bride), a group of ecstatic women in ‘iro’ and ‘buba’— traditional attire worn by Yoruba women from southwest Nigeria — huddle around a magnificent traditional bride, rejoicing in the promise of happiness for their friend through marriage. The scene is full of joyful noise, but Fatile layers a darkness within, evident in the woman’s signature black, shadowy eyes. These ghostly eyes are a dominant motif in the artist’s work, and in this painting, the darkness is restrained to realist effect; a darkness that recontextualizes expressions of joy to suggest lingering pains, the bad times, and the tragic histories ever present within them and us.

We see such pains most vividly in Fatile’s painting Most Coloured, Most Visible. A Black woman with short-cut hair, naked and rendered in oil paint on batik fabric, lies crumpled against a white background. The pattern of the batik rises from her skin, resembling scars, open wounds, or an embodied cultural tapestry and personal history searing the flesh from within. The image is brutal — introspective but intrusive — as I looked, I became both viewer and voyeur.

Fatile reveals here the complex inner life of the Black and African woman’s body, which is formed by its history as well as harmed by it. Within a single gaze, the body is reduced to a commodity in life and elevated to a spectacle in death. I imagined this woman to be another friend of the bride who, perhaps due to some vague illness, couldn’t make it to her friend’s wedding. Her eyes are dark and muddled, two voids staring outward, saying nothing yet revealing everything as a dim, lifeless soul. There is pain, which may have started within the borders of language, but has long since escaped into a blacker, mute, mental night country.

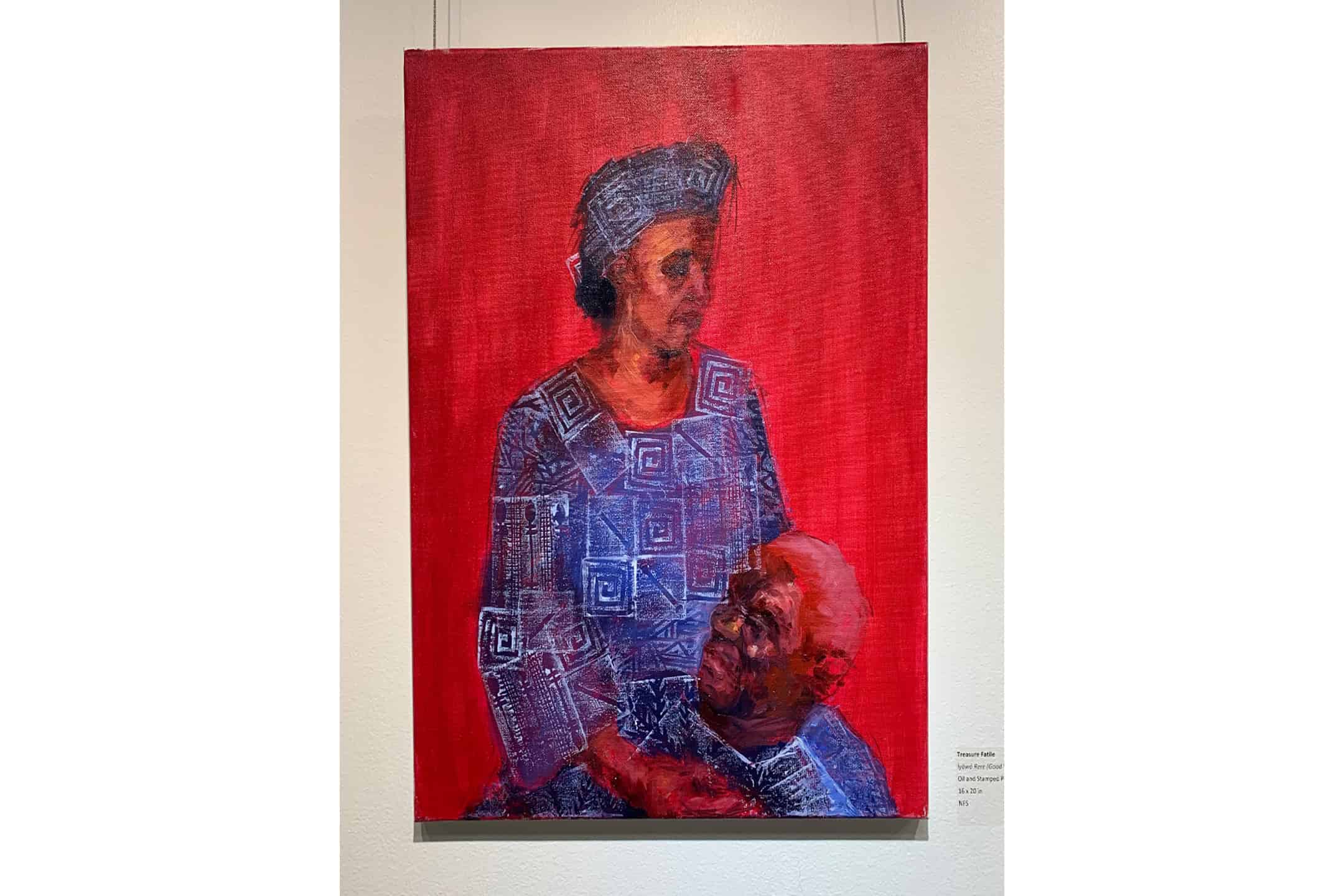

In Íyàwó Rere (The Good Wife), an old woman holds an old man in her lap in a depressing marriage portrait. Against a blood-red background, their eyes — and entire faces — appear as brown-black blurs, indicative of their eroding personhood. While the old man’s face is depicted with rougher strokes, his smoother, more pliant wife fills the frame. Fatile emphasizes the cost of duty on the African woman and the quiet suffering of the benign mother who aspires to an imposed archetype. This role demands from women the intimate sacrifice of gendered subjectivity, assuring degrees of destruction while ensuring a lively home and a satisfied patriarch.

In the digital paintings Blue and Daydream, Fatile exposes the imposition of the sacrifice in infancy. Young Black girls stare into nothing with dead eyes, or with eyes rolled back in mixed pain and pleasure to reveal the sclera — wide open, toward the viewer. Here, the mystic enters silently.

At first, there is a battle of wills between personal autonomy and the cultural binds of duty and sacrifice. These girls are caught in a struggle against the purity imposed upon them and the unnatural forces that possess their bodies, transforming them into spiritual vessels or conduits for society’s enjoyment.

There is another woman, an untitled portrait of a mix of oil paint and plastered fabric. In splendid bridal iro and buba, she resembles the Immaculate Heart of Mary for a post-colonial Nigeria. Her arms gesture outward and upward in a show of submissiveness. Her headdress sits like a crown. A circle of batik fabric, featuring the same pattern as in Most Coloured, Most Visible, forms a halo. Her face pours out immeasurable sorrow. Her liquid dark brown eyes swirl with bliss and pain.

In some of these paintings, Fatile constructs a Black Madonna — the image of the Blessed Virgin Mary — trapped in the pose of piety, suggesting possession and holy passion in balanced expressions of gratification and mute suffering.

All of Fatile’s women may represent the same tortured woman in different strokes. My interpretation aligns with the paradox at the heart of the Virgin Mary; the woman struggles against authority while also marrying it. She is both the virgin and the mother. In The Good Wife, she embodies Mary, while her husband symbolizes the infant Christ. She is exposed, sullied, and ordinary, but she is also hidden, holy, mysterious, and miraculous. As the standard of peace, purity, and transcendence, the tortured woman is also the epitome of suffering and a woman’s incompetence before the heavenly judges: God and man.

Fatile unmasks the religious morals governing the sect of womanhood for the modern African woman and girl. She brings attention to the silences, duties, and sacrifices of the female experience — truths that are especially acute for Black African women who are often overlooked by mainstream feminism. By uncovering these silences, Fatile exposes us, the viewers, to our conformity and the comfort we enjoy at the expense of those we love.

Recently, Fatile received the Mississauga Arts Council award for Emerging Visual Artist in Traditional Forms, which recognized her “exceptional talent” and “unique artistic expression and commitment.” Her paintings have enough force to shake up old powers, and with enough support, Treasure Fatile just might accomplish exactly what she is setting out to do.

No comments to display.