Content Warning: This article contains descriptions of sexually explicit content.

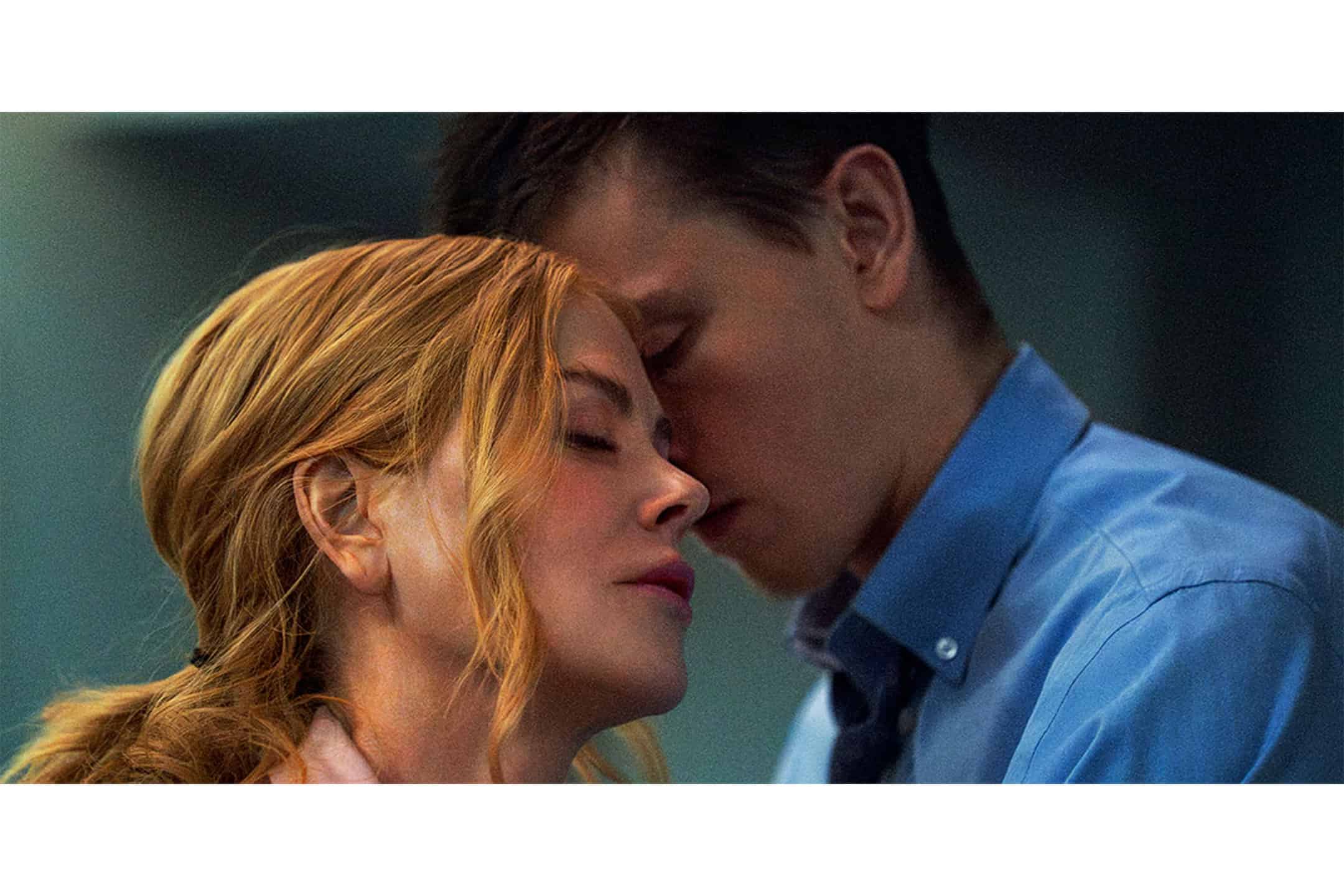

Babygirl, directed by Halina Reijn and starring Nicole Kidman, fixates on one question: who holds power in sexual dynamics?

Kidman plays Romy, a ‘bossbabe’ CEO of an Amazon-esque company. She engages in an extramarital affair with one of her interns, Samuel (Harris Dickinson), while juggling her commitments to her family and husband, Jacob (Antonio Banderas).

The dynamics between these three actors are absolutely electric.

Kidman portrays Romy’s insecurities and sexuality with a rawness that meshes well with Dickinson’s portrayal of Samuel, whose insecure dominance is palpable. Samuel may be one of the most obnoxious characters ever put to screen. Every time he spoke, all I could think was, ‘men really do have the audacity’ — yet he also displays moments of vulnerability.

His voice quivers when giving Romy commands and though he craves the dominant role in both sexual and social situations, he stumbles through it awkwardly, revealing his naivety. Samuel’s unlikability is crucial, especially when compared to his competitor, Jacob.

Jacob exudes a kind demeanor. Warm and caring toward his family and comfortable in his creative role — an intriguing contrast to Romy’s dominance in the corporate world.

Babygirl is an erotic-thriller, drawing inspiration from 90s films like Basic Instinct. In a post-film Q&A, Reijin acknowledged that many erotic-thriller films are framed through a ‘male gaze.’ She explained, “I wanted to make my own sort of answer to that, and make a movie about sex and female desire… and talk about everything I’m very ashamed of.”

An important aspect of Babygirl is its use of gender dynamics. Despite women’s increased presence in the workforce, figures like Romy — who is a CEO — remain rare, with barely 10 per cent of Fortune 500 CEOs being women. Even though Romy holds power over the other characters, she struggles to fulfill her personal desires and is constrained by their expectations. She confines herself and her sensuality due to societal shame. Reijin reflects on how women are still constrained by gender expectations, despite professional advancements.

Romy is portrayed as a strong, well respected figure in her industry, but she lacks the emotional vulnerability expected of women both at work and at home. When she feels a desire for Samuel early in the film, she punishes herself for it. After fantasizing about Samuel, Romy forces herself through an intense beauty routine, trying to regain the strength and control she feels she needs to project.

In their first sexual encounter, Samuel instructs Romy to get on her hands and knees and eat a candy from his palm. The scene then shifts, where Romy is forced to the floor while Samuel masturbates her. This scene focuses on Kidman’s performance rather than graphic details.

Reijin explained in the Q&A that, “I don’t like graphic sexuality… personally, I only like the suggestion… it’s way more sexual and almost embarrassing to watch [Samuel] give [Romy] a command and her doing it.” The subtle approach here enhances the feeling of semi-awkward tension during sex scenes and adds to the shots’ realism.

Romy is a deeply insecure character, despite her powerful position at work. She faces belittling comments from Samuel and her other colleagues, who criticize her perceived inability to be emotionally vulnerable and her indecent conduct with Samuel. This dynamic creates an intense, awkward, erotic tension in every scene between Romy and Samuel. Although the film’s sex scenes are not explicitly graphic — with minimal nudity from both Kidman and Dickinson — the interactions between them are imbued with a gripping and potent sensuality that permeates each moment.

No comments to display.