‘Female rage’ movies are having their moment. Older films such as Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession (1981), featuring Isabelle Adjani’s iconic bloodcurdling meltdown in a subway tunnel, have become a favourite among social media girl bloggers. The X trilogy, starring Mia Goth, offers another example of an unchained woman protagonist, with her murderous rampages tinged with feminist ecstasy.

When first presented with the plot of Nightbitch — a stay-at-home mom’s repressed anger slowly turns her into a wild dog — I had high expectations. Would this be another standout in the growing canon of female rage movies?

Unfortunately, while director Marielle Heller’s Nightbitch seemingly tries to be a sort of plucky dark comedy, the film plays it far too safe to be dark or genuinely funny.

Amy Adams’ performance as the unnamed protagonist, Mother, is generally strong with a comedic edge, but eventually sabotaged by Nightbitch’s contrived screenplay. Each time Mother breaks into a rage at her overly-chill husband (Scoot McNairy), her dialogue is packed with the same feminist witticisms and jargon you might hear in a Michelle Obama speech. It felt as though Heller were trying to wink-wink nudge-nudge the audience: “Hey you guys, I know this stuff!” Several times throughout the film, I thought to myself: “Didn’t I read that line on Twitter?” As a result, Mother’s exasperation with her daily routine comes off with about the same authenticity as a busy mom in a Subaru advertisement. Too busy superficially signalling its ‘feminist’ ethos, Nightbitch fails to disturb, unsettle, or inspire.

As a dark comedy, Nightbitch fails to convincingly subvert its idyllic suburban setting where it takes place. The walls of Mother’s house — where she supposedly feels confined like a caged animal — never creak with darkness. The contrast between ‘good mommy’ and ‘bad mommy,’ ‘night mommy’ and ‘day mommy,’ never reaches a truly jarring climax.

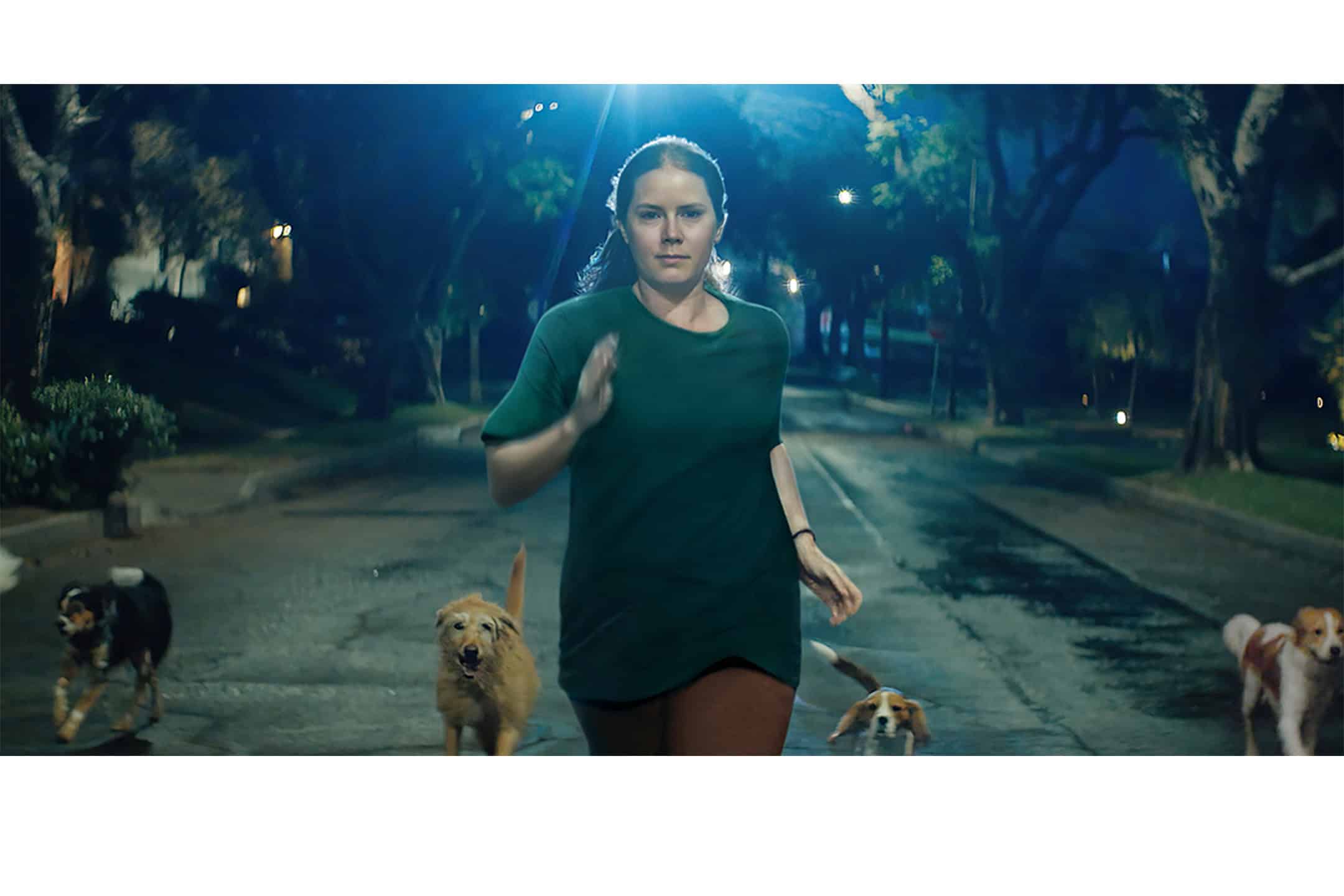

Nightbitch particularly lacked the body horror element one would expect from a film about a woman morphing into a dog. The story didn’t linger on the toll of this transformation on her body, nor witness her wreak havoc in a half-woman, half-animal feral element. Its handful of gruesome shots felt out of place. Rather, Nightbitch takes its central metaphor all too literally: Mother turns into a CGI-rendered German Shepherd. If watching a dog gallop down a tree-lined street was supposed to symbolize Mother’s fearsome final form of unbridled rage, it was laughable. Heller’s rich opportunity for gore and suspense was defanged and replaced with something far more domesticated.

In fact, Mother’s canine transformation is handled so clumsily that my jaw dropped several times in the theatre. It begins when she checks out a book about women deities from the library, which introduces us to powerful half-animal, half-human goddesses from Inca or Hindu mythology. As Mother unlocks her ‘primal’ side, she starts playing ‘doggies’ with her son — buying him a dog bed because he sleeps better on the floor, and deciding that they eat with their hands as dogs do. We watch her make growling noises while shovelling mashed potatoes into her mouth — a scene meant to show Mother unleashing her inner mama bear.

Not only did these scenes muddle the film’s driving message, but they also came off as painfully cringe-worthy. Many cultures traditionally eat with their hands and sleep on the floor, yet we watch Mother ‘discover’ these practices in a way that feels dismissive. “Maybe we’re all just animals,” she earnestly muses, as the movie closes with her family living in a pillow fort — an upper-middle class American parody of primal living. The entirety of Nightbitch reeks of well-meaning white naïveté: by trying to simultaneously turn Mother’s descent into a feral creature into an Eat Pray Love moment, the film achieves neither.

One almost feels pity for Mother, clumsily trying to grasp a communal, intuitive ethos of motherhood that many mothers outside global Western civilization already understand. Yet, the film fails to touch upon the root of her struggles — the isolating nature of suburbia. Instead, Mother finally fulfills her dreams by divorcing her husband, who moves into a new condo with their child. Only then when she is left alone can she create the art she had bottled up during her motherhood, hoping to prove her worth to him.

Beyond the fact that Nightbitch will resonate as cathartic or relatable primarily to a privileged demographic of women — two homes on one income, really? — the film’s protagonists only grasp their lesson superficially. Overall, Nightbitch follows a dated Western second-wave feminist narrative: women were trapped as housewives until they got jobs, left their husbands, and found self-actualization.

Nightbitch never fully leans into its eerie premise, offering about as much feminist nuance as a tampon commercial. If you’re a Gen X mother who considers Kamala Harris and Taylor Swift to be #girlboss icons and whose home looks like a Pottery Barn ad, you might enjoy this movie. But for those seeking a film that delves into the complexities of motherhood with the real depth and all its gruesomeness, I suggest looking elsewhere.

No comments to display.