Queer is an early and relatively minor novella written by William S. Burroughs in the ’50s which remained unpublished until 1985. In adapting Queer into a script, director Luca Guadagnino and screenwriter Justin Kuritzkes, who previously collaborated on Challengers, intended to finish the narrative with respect to “how Burroughs would have finished it.”

I find this a little disingenuous. The screenplay is a largely sterilized treatment of the original material, muddled with a few biographical details pinched from Burroughs’ The Yage Letters.

Daniel Craig plays Lee, a wealthy American expat in Mexico City whose only business expenses seem to be booze, cigarettes, and prostitutes. The politeness of Craig’s expressions swims with a sub-surface, self-destructive libido which the film allows to seethe at its finest moments.

The main character is something of a Burroughs impression — Lee is an author-insert after all — which Craig plays with pathetic mannerisms usually obscured in Burroughs’ patterns of self-presentation: quicker to embellish a lecherous hunger for boys than any degree of tenderness. Craig’s performance is very effective and so is his co-star’s, as Allerton (Drew Starkey) carries a plain ease of seductive gesture without ever allowing himself to fully decompress in a situation. He’s pulling himself along with an ambiguous and sleek double-bind, which is appropriately frustrating.

Queer is constantly pressured by these biographical details. For example, the motif of the centipede repeats in various minor circumstances, which I believe is Guadagnino referencing Burroughs’ outsized interest in the myriapod as a thousand-legged representation of social control.

In this adaptation of Queer, this symbolism is quite confusing, with the centipede positioned arbitrarily within ‘trippy’ sequences of shots. These are somewhat reminiscent of the dream-like stage realities of playwrights like Jean Cocteau or George Powell, but I found that Guadagnino’s overreliance on misdirection disrupts the discontinuous relationship between the scenes to the point of monotony. It wasn’t that these biographic detail additions were necessarily predictable, but that they were stagnant and couldn’t really dynamize or compel interesting cinematic recognitions in the same sense that Burroughs’ prose excites on the level of language.

Guadagnino’s blocking — the details of actors’ place and movements within the camera frame — weighs out striking character dynamics. As a form of visual storytelling specific to character positions within a shot, it is conventionally skilful. However, he struggles to reorient those sensibilities when the script necessitates a shift in the logic of these compositions.

His depictions of substance usage recycle a small selection of relationships: namely Lee’s protoplasmic and otherworldly impulse to assimilate into Allerton, which Guadagnino represents with the double-exposure of phantom fingers mid-molestation. It’s clear that this use of cinematic language is communicating a cosmically grand pining, which is why I’m a little suspicious of Guadagnino’s interpretation of the text. He cut extremely little in the translation from novella to screenplay but notably omitted the section where Lee considers soliciting sex from thirteen-year-olds by dangling a few Sucres — a currency used in Ecuador prior to 2000 — for them. In interviews, Guadagnino claims the movie’s thematic concern is “the ultimate love story.”

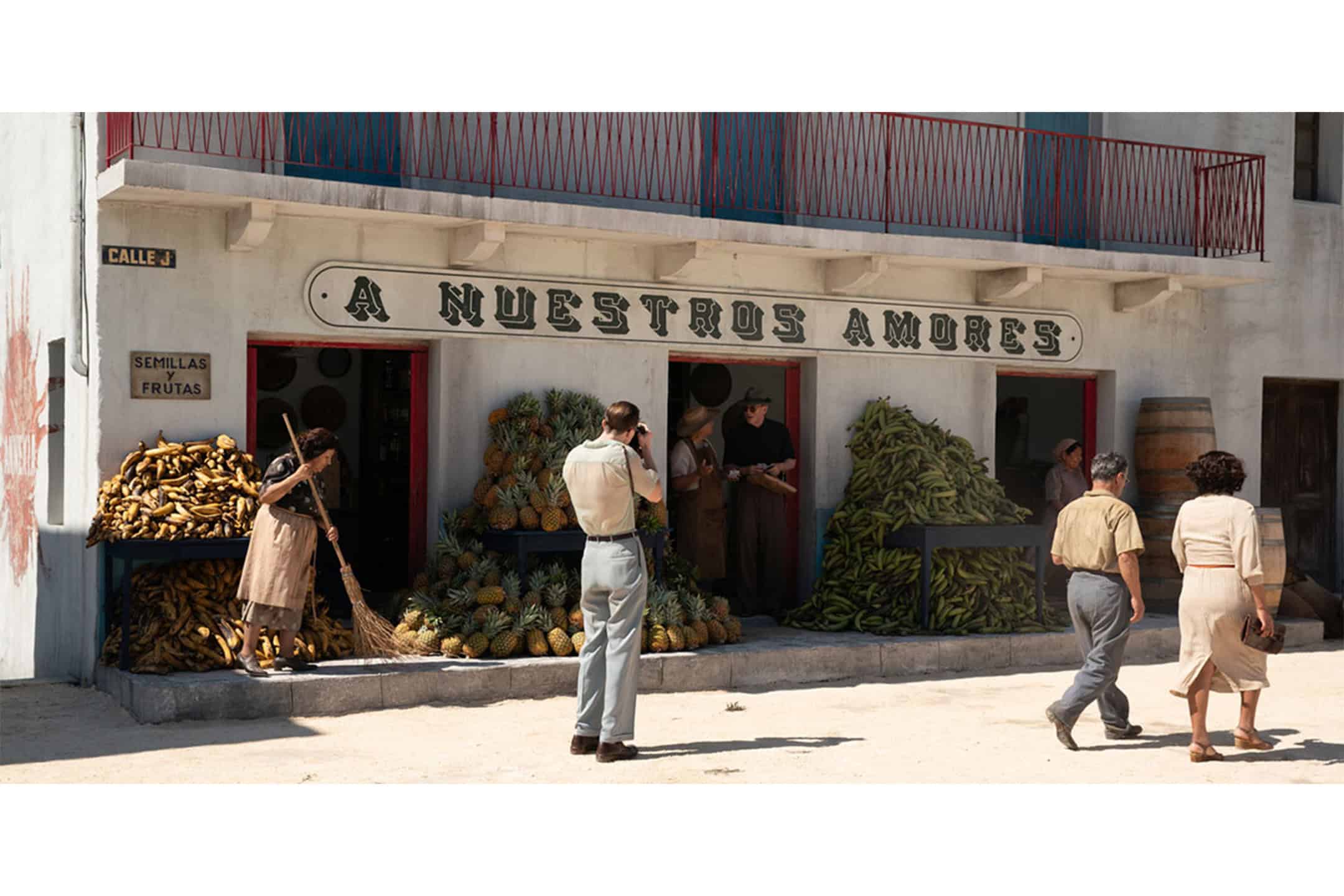

Since Queer was shot in an Italian studio, much of the set design is digitally-generated. The clay roofs and hilltops all slant together with this gloss of wrongness that translates visually as sludge. At points, the unreadability of any landscape is quite Burroughs-esque, but Guadagnino’s romantic presumptions assure the results never quite derange the senses enough to be interesting.

The exception to this is the occasional shot layered with the Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross score, which is a kinetic, synth-charged network of orgasms. There are a few indulgent and anachronistic needle-drops, like Nirvana’s Come as You Are — presumably a wink at the collaborative spoken-word tracks released by Burroughs and Kurt Cobain. The tonal structures are hideous and combust with a strange energy of living tissue that the film’s other stylistic commitments can’t match in velocity. Even the sex, which, although explicit and shot with obvious artifice, proves too straightforwardly appetizing to suggest anything erotic.

In much of Burroughs’ work, substances and languages are transmitters of disease imported from an extraterrestrial zone of future-time. While watching Queer, I was similarly affected. Guadagnino’s depiction of the early author has a certain larval hum and the sum of Burroughs’ biography is actively converging with the film’s fiction. Burroughs is the turbulence in the repetitive perfection of the scene, he’s already here, and he’s already written novels more compelling than Guadagnino’s adaptation of Queer.

No comments to display.