For a science fiction writer in the ’70s, people currently live in a world with an incredible futuristic landscape. We have technological advancements allowing individuals to talk to a friend on the other side of the world, seeing them lit up by the same sun that is setting outside their window. There is an invisible online world that is an unparalleled resource, with forums, websites, and scientific information about every topic — way more than a single person could ever truly research in their lifetime.

Despite all of these incredible advancements, the actual future isn’t going so well. When news headlines are filled with protests, fears around inflation, and academic institutions threatening police action against students who pay them thousands of dollars to attend classes, it seems natural to turn to science fiction as a form of escape from reality or relaxation.

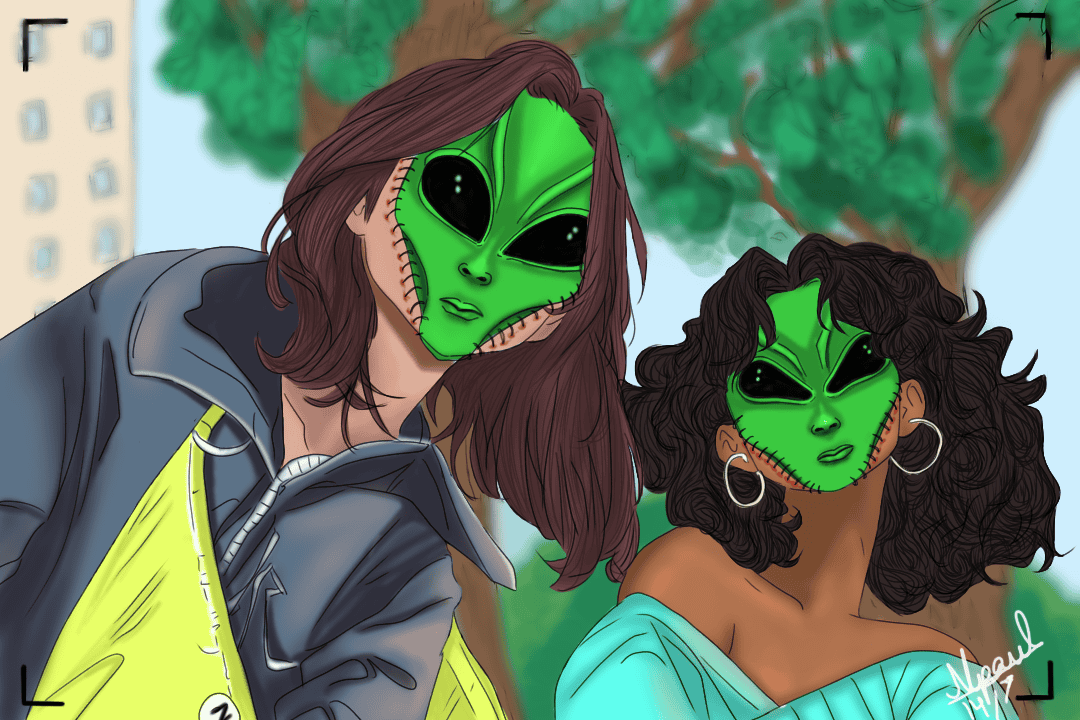

In the heyday of pulp fiction — graphic, punchy, stories popularized in the mid-twentieth century that were either printed on cheap paper or wood pulp, hence the name — what was popular reflected the social fears or triumphs of the decade; see aliens and space invaders during the Cold War.

Even science fiction novels like David Brin’s The Practice Effect posed a ‘what-if’ for the state of affairs at the time of writing, asking how the world might be different if one minor thing was changed. Brin’s novel flips the rule of entropy — where the more an object is used, the better it functions or appears, instead of wearing out — resulting in items that are centuries old and in better shape than a chair that was made the day prior.

Science fiction gives us options for imagining alternative realities. When there’s no limit to worlds that can exist — or restraints on space travel — these fictional characters can be whoever they’d like and live in ways we might not want to admit we’re deeply envious of.

There is a pervasive sense of disenfranchisement and disillusionment with the current state of affairs. Turning to literature or other forms of entertainment is one way to handle things — to escape a dysfunctional world and give ourselves a necessary mental break.

Kelly McCullough, an author who has written for science fiction magazines like Uncanny and created comics with NASA, argues that “the idea that escape is inherently tainted is fundamentally an argument of privilege made primarily by people who have never been in a position where they needed to escape from a situation when actual escape was impossible.”

The science fiction realm allows audiences to abscond from everyday horrors, but it is not all pure fantasy: after fleeing reality, audiences are then equipped to confront it.

As much as the galactic worlds of Star Wars or Star Trek offer aesthetic pleasure, the themes that appear in the genre also bear solid reflections in the real world. While we bring our own experiences to the page when reading, these stories also reflect our lived experiences to us. Therefore, people use the long-standing tradition of storytelling to explore their own failings and anxieties, which functions as a way of engaging realism in their narratives.

Science fiction is our world, but with a viewer or reader’s agency, it is a fantastical, turmoiled world that we choose to be immersed in. The reader’s freedom to explore new themes or experiences without consequence allows them to have a sense of agency and safety.

Though the future isn’t looking to be as bright as writers like Brin hoped for, I’d like to argue that the divide between what we imagine and what is real about our possible reality is thinner than we think. Just because technology like the hyperdrive from Star Trek hasn’t been invented yet doesn’t mean that fictional worlds don’t have real-world implications, inspiring the next generation of writers, scientists, or engineers whose creativity and visions might even save lives.

We have the ability to write the realities we want to see, whether for aesthetic reasons or to see ourselves represented in the real world as in literature. Hopefully, as the world progresses, we can use science fiction to escape into a better future.

No comments to display.