Let’s take a tour of the average voter: a civilian who is passionate about a small salad of topics. On other political issues, they have only a cursory understanding of complex and pressing issues and they are often uninterested in learning more, particularly with social media being a source of news and political information. Importantly, the average person is not exempt from cognitive biases and frequently acts in ways that seem bizarre or irrational.

What are cognitive biases?

Cognitive biases are mental shortcuts our minds use to help us think faster and navigate situations based on a subjectively constructed reality. However, these cognitive biases can sometimes lead us astray. If we’re not careful, they can undermine our ability to engage effectively in a democratic society. An example is during an election, when presidential candidates introduce themselves to the nation; they may use exaggerations, exploit emotions, appeal to authority figures, make confirmatory statements, and employ self-aggrandizing rhetoric to make an impression and win votes.

In a 2005 correlational study from Princeton University published in Science, Students were shown one-second glimpses of unfamiliar political candidates and asked to judge their competence. Remarkably, these snap judgments were in line with the outcome of elections about two-thirds of the time, significantly better than random chance. This rapid judgment was made using the students’ pre-existing cognitive biases.

We are influenced by the opinions of those around us

A candidate’s confidence is as important as the policies they advocate. The confidence heuristic occurs when people assume that a confident speaker must be correct. This can elevate charismatic leaders while overshadowing more qualified, but less assertive candidates. Regardless of what your personal politics are, one reason former US President Barack Obama garnered widespread favour — even in traditionally Republican states — was the charismatic, charming, and confident attitude he brought to speeches and debates.

There are other ways we falter based on first impressions. Anchoring bias occurs when initial numbers and data have a disproportionate influence on our decisions. For instance, the government’s proposed budget can become an anchor around which lawmakers and the public negotiate, often failing to consider whether the initial figures are appropriate. Similarly, opening statements in a debate can skew our perceptions of a candidate, shaping our overall opinions about their capabilities.

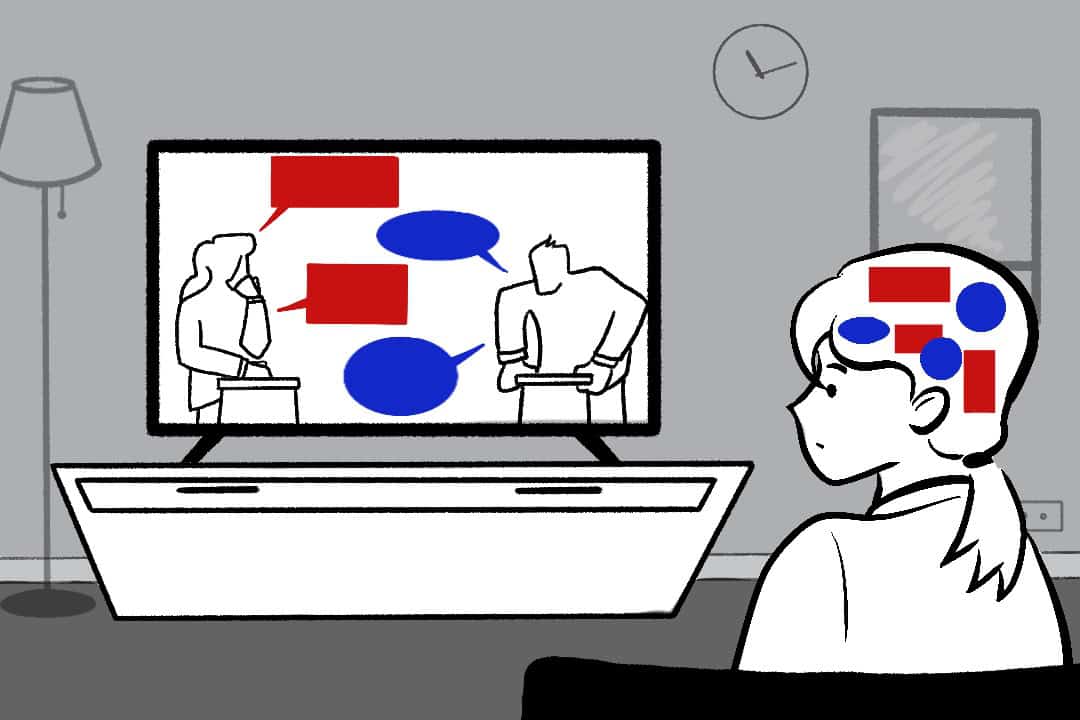

In addition to anchoring bias, another common bias that plagues our decision-making is confirmation bias, where we tend to pay more attention to information that aligns with our preexisting beliefs, ultimately reinforcing polarized views.

Our biases run deep, leading us to sometimes conform to a group’s beliefs that we don’t necessarily agree with. This is known as confirmation bias. In a 1955 study of conformity, voters were asked, “Which one of the following do you feel is the most important problem facing our country today?” They could choose from five options: economic recession, educational facilities, subversive activities, mental health, and crime. When asked individually, only 12 per cent answered ‘subversive activities.’ However, when placed in a group that already endorsed ‘subversive activities,’ 48 per cent of the new participants agreed with the group. This strong desire to conform to a group significantly shapes our choices, leading us to maintain these decisions long after the ground influence has faded, both in the political arena and beyond. Conformity studies like these have been replicated as recently as 2023.

Biases affect everyone, whether you’re conscious of it or not

It’s not only voters who fall prey to biases; politicians do as well, often with dire consequences. In 2017, former President Donald Trump justified sending more American troops to Afghanistan, and said, “Our nation must seek an honourable and enduring outcome worthy of the tremendous sacrifices that have been made, especially the sacrifices of lives.” This statement reveals a clear example of the sunk cost fallacy, which occurs when individuals continue to invest in a poor decision due to resources already expended, even when it’s no longer the best course of action.

A 2005 report to former US President George W. Bush on the events leading to the Iraq war stated, “When confronted with evidence that indicated Iraq did not have [weapons of mass destruction], analysts tended to discount such information. Rather than weighing the evidence independently, analysts accepted information that fit the prevailing theory and rejected information that contradicted it.” This cognitive bias had dire consequences, as nearly 300,000 civilians lost their lives due to America’s invasion of Iraq, illustrating the tragic cost of poor political decisions made without recognizing the biases that influenced them.

With biases shaping our political landscape, it’s natural to ask why we fall prey to such heuristics. Evolutionarily, there may have been many situations where swift decision-making was more important than complete accuracy, like in life or death scenarios. Most knowledge within a species is shared; if someone presented you with information contrary to what you’ve heard, your safest bet was to ignore it. This illustrates the evolutionary incentive for cognitive biases, such as confirmation bias, to evolve. These heuristics simplified a complex world and generally led to reliable decisions.

However, in today’s intricate political environment, these same biases can mislead us. With the US presidential elections approaching and the world facing extreme polarization, rampant misinformation, global conflicts, and economic instability after COVID-19, it is imperative to check our biases and reflect on how they may be shaping our beliefs and choices.

No comments to display.