Content warning: This article discusses homophobia.

In an age where the internet makes connecting with millions over shared interests or traits easier, forming real-life social connections can feel comparatively confusing.

Social media is a relatively recent addition to the long history of human socialization and adds a unique layer to how we interact. As someone with unlimited screen time and a knack for procrastinating, I often find myself scrolling through my X feed throughout the day — against my better judgment.

As someone who identifies as queer, my feed is, by algorithmic design, filled with fellow queer users that turn to X to connect with others in the 2SLGBTQ+ community. Through this, I came across a post from a user named @insanhitty — also known as Sanhitty Peta on Instagram — who shared a photo of himself at an upscale event.

In this photo, Peta wears a houndstooth jacket and a black sleeveless patterned shirt. He wrote: “I’ve got TERRIBLE gay face but pls help me, how do I let girls know I like girls when I interact with them, ESPECIALLY when I find them attractive[?]” Another user, @2sandz quote-reposted with the comment, “Not wearing a sleeveless lacy button up would actually help you greatly.”

In this post, Peta expresses the struggle of failing to attract women as a result of his non-heteronormative self-presentation. Upon first reading @2sandz’s reply, I laughed in agreement with their point. Identifying as queer often involves subverting gender-based expectations. In a heteronormative culture, non-platonic feelings toward men are often labelled as a ‘female’ tendency, so when a man expresses such feelings, it’s viewed as ‘emasculating.’ Whether intentional or not, @2sandz’s comment suggests that men wearing a textile-like lace, typically associated with women’s fashion, reflects a queer, gender-flipping style of self-expression.

At the moment, though, I chose not to think too hard about this and took the post purely at surface level. Many others must have done the same; @2sandz’s reply has amassed more than 106,000 likes since it was posted — a number that continues to grow.

I kept seeing more and more posts on X about Peta, with users making similar jokes about how he is ‘dressing gay’ and, as a result, not attracting the attention of the opposite sex. From this, I realized that I — and many others — share similar ideas about gendered fashion aesthetics and how they affect perception, since many people found a similar conclusion about where Peta went ‘wrong’.

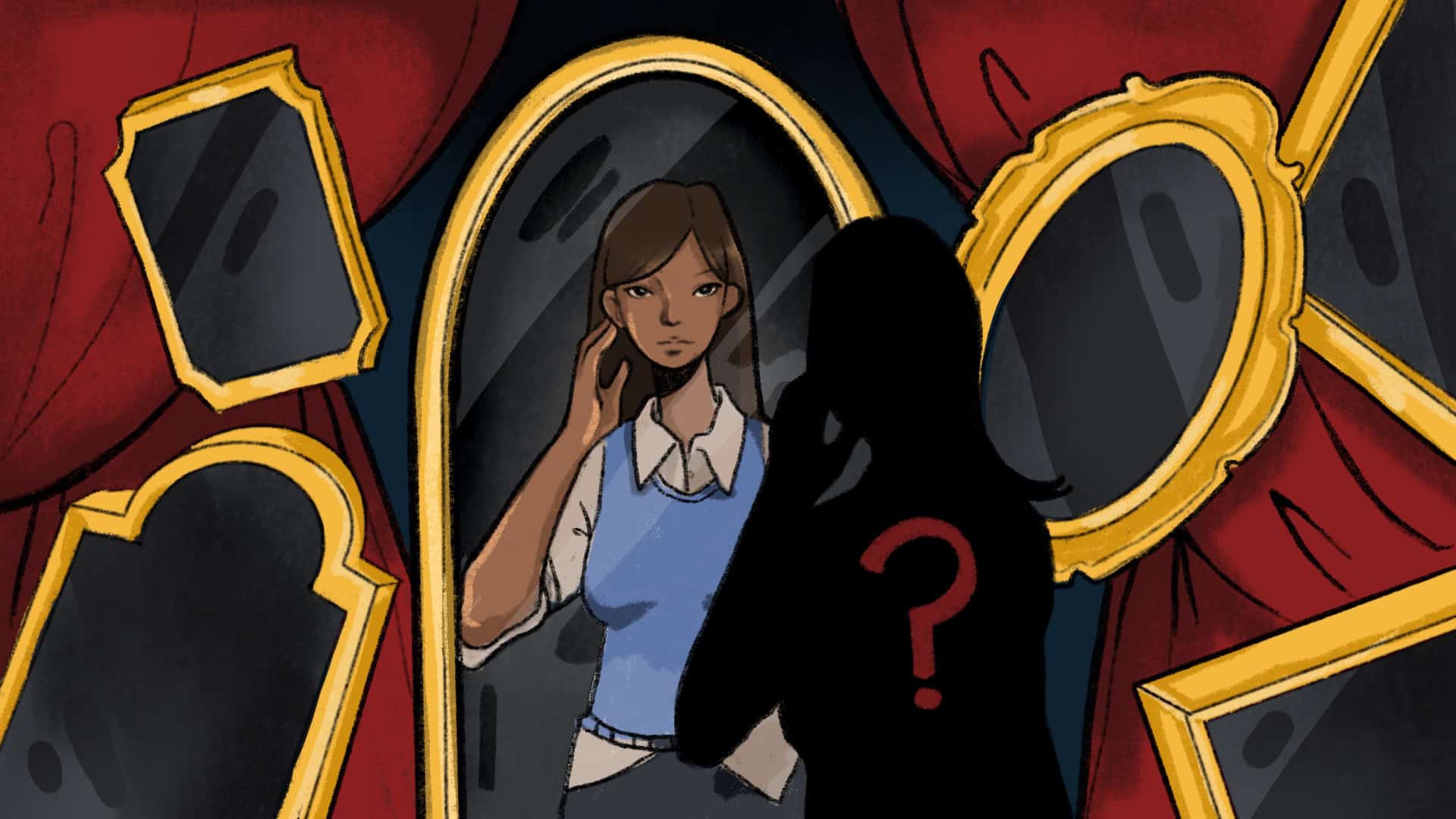

Not long after seeing these posts, I started to overthink the idea that one’s fashion choices signal exactly who they’re attracted to. If someone’s personal style subtly involves ‘dressing gay’ when they aren’t, can it truly be authentic?

I hadn’t given this much thought before, so I began to reflect on how I present myself and the impressions my fashion choices leave on others. What does ‘dressing gay’ mean in a culture where sexuality and gender are increasingly viewed as fluid? Is the ability to easily spot ‘our kind’ in public a good or a bad thing? And how are queer fashion trends being co-opted by those outside the community to fit in? Questions like these may arise as we explore the cultural impacts of some of Gen Z’s favourite apps.

A captivating broken telephone

To begin analyzing the relationship between identity and fashion, I decided to look inward to find similarities between myself and Peta regarding where we get fashion tips. When I look at my wardrobe, how do I decide what to wear?

Sure, I might go through the arbitrary process of pulling out random articles of clothing and trying them on to see if they work together. But my sense of which pieces work together will differ from someone else’s — everyone has their own personal style.

Where do I go for outfit inspiration? Naturally, I turned to Pinterest. The most aesthetically pleasing of apps, serving as the headquarters for the niche trends to follow while still convincing all your friends that you just whipped it all together on a whim. Already, Peta and I have something in common: we both totally trust social media for style help.

With the world at my fingertips, I can explore what Pinterest has in store for me — my most recent dive into the platform has recommended categories like “grunge clothes” and “dark academia outfit.” These recommendations are quite eerily on point with the music and books I have recently engaged with, but if I like the pictures they show me when I click on them, I don’t think about it too deeply.

For some fellow Gen Z students at U of T, Pinterest’s recommendations suggest they should follow certain trends based on their identities.

“I sometimes search for specific clothing items I see — recently it’s been cute tops that come with a thin scarf, [which] I’ve seen a lot in East Asian fashion,” said fourth-year drama specialist Elizabeth So. As a Chinese-Canadian, So observes a connection between her cultural identity and the clothing pieces Pinterest recommends her, indicating that the platform’s algorithm conflates human traits with material self-expression.

Feeds will differ from person to person, but So and I have both noticed that fashion trends often affiliate certain lifestyles with specific ‘aesthetics’. Through online posts and fast-fashion advertisements, you are sold a stylized version of your own identity in a one-stop shop. These ads may make you feel inadequate, as if dressing like these Pinterest models will somehow validate you in your community. Advertisers prey on these insecurities for monetary gain.

“I’m so used to things [like artificial intelligence recommending these trends that] my brain just blurs it out,” said So, reflecting on the normalization of targeted trends. Though individual human beings may not be actively curating the algorithm, the lasting, real-life effects of these micro-trends exist without us even consciously realizing them.

‘Dressing gay’ and fitting in

Popular culture today imposes fewer restrictions on the ways individuals can use fashion to express their identities, regardless of sexuality or gender.

It never used to be that ‘gay’ or queer fashion choices were part of mainstream culture, or even seen as means of making a profit in general — many of these fashions existed long before the internet or social media, and were created by the 2SLGBTQ+ community for an existential purpose.

Sure, it was for fashion’s sake, but most importantly, it was for survival. In the journal Symbolic Interaction, researcher David J. Huston wrote in his article “Standing OUT/Fitting IN” that, from the 1950s to the 1980s, “the connection between appearance and identity became salient for an individual’s life and safety.”

“Being ‘gay’ meant being visible or standing out, typically through appearances that broke gender conventions,” wrote Hutson. Drag queens, butch lesbians, and other members of the queer community were persecuted for their identities and the way they chose to visually express themselves. To fit in with the dominant heterosexual society, 2SLGBTQ+ individuals would alter or censor the way they dress so that they would be presumed as straight, so that they need not worry about whether or not they will make it home safely at the end of the day in a society rife with homophobia. But, that didn’t stop queer people from finding themselves and others like them.

Hutson mentions ear piercings, tight clothes, high-legged men’s boots, and methods of hairstyling among many other styling signals that were historically used by queer communities. They were silent forms of self-expression, subterraneously setting the bar for experimental and artistic fashion permanently. Hutson also notes that queer fashion trends even varied based on race, gender, and country of origin. Dressing ‘gay’ can mean a hundred different categories of fashion.

Dressing ‘gay’ has multiple layers, a plethora of styles that have been built out of forced shame and hardship. Author Lisa M. Walker remarked in “How to Recognize a Lesbian”, from the special issue “Theorizing Lesbian Experience” in the journal Signs, that lesbian and gay theorists in the 1990s were noting the “performance of visible differences” between queer and straight fashion choices as key points of political autonomy, as these styles could be used as a means of dismantling pre-conceived ideas regarding gender, race, sexuality and other identities, announcing it as not only clothing but a call to action.

However, it may be disconcerting for many queer people to see how little the political background of queer fashion is understood today, spearheaded by internet trends on my Pinterest page with each new login.

Queer-coding viral aesthetics

Okay, now picture this: you are at a bookstore, browsing through the latest novels in a curated section of greyscale book covers. You pick one up and read the synopsis on the back, the story might be set in the 1980s at a prestigious American Ivy-league school, or in the 1890s at a countryside mansion in England. You can expect the main characters to be men, and between two of these young men, there are unspoken feelings and an unacknowledged tension.

If you’re like me, this description will resonate with the storylines for many of the books you love. Notably, the brooding setting of the story and the homoerotic subtext provides some of the quintessential tropes for what is known as ‘dark academia’ — an aesthetic trend running rampant all over Pinterest and beyond. Amongst the online queer community, the seemingly androgynous staples of dark academia fashion, such as blazers and crew-necked sweaters, have allowed for the aesthetic to gain popularity. And when allusions to queerness are present in ‘dark academia’ books, like in Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, it’s even easier for queer people to connect to these stories.

The dark academia aesthetic is relatively new. Tartt did not write her books with the dark academia trend in mind when they were published in the 1990s. Aida Amoako, in an article on JSTOR Daily, dated the dark academia trend to the mid-2010s on Tumblr. Kristen Bateman in the New York Times stated it skyrocketed in popularity during the COVID-19 lockdown. Dark academia has now become an aspired lifestyle — photos of two sweater-clad gentlemen almost holding hands leaning against a brick wall, or a bookshelf, are now everywhere on the internet under the tag “dark academia.”

Here’s the problem: the dark academic archetype’s toeing of the line between definite 2SLGBTQ+ representation and incredibly close friendship is at best poor representation and commodification at worst, when the aesthetic and its superficial queer representation are taken as aspirational content by internet users and Pinterest algorithms.

When I interviewed Izzy Friesen — a graduate student at U of T studying classics — they explained how the dark academia aesthetic “treats queerness the same way it treats academia [by] engaging with it at a surface level or the level of the aesthetic.” This evasive approach avoids engaging with the nuances of these queer-coded characters and understanding why queer people might relate to them.

Dark academia books frequently end in tragedy, discussing the perils of rigorous higher education as the characters repress their authentic selves in order to succeed academically. Conversely, the visual aesthetic, as seen on Pinterest, cannot take this nuance into account, selling users the idea that they can be just like their favourite queer-coded character if they dress according to their recommended Pins.

Social media algorithms take such archetypes perpetuated in culture and co-opt them into attention grabbing aesthetics for users to consume. On platforms such as Pinterest, the dark academia aesthetic thus attracts the same audiences that queer subplots in literature appeal to. Admirers of dark academia are therefore compelled to indulge in an aesthetic perpetuation of a superficial representation of queer identity.

Friesen continued, “People are treating academia as something that can be flagged like queerness but misunderstanding that [beneath] the flagging, queer people actually have lives. Basically, surface level understanding of both queerness and academia begets surface level [representation].”

I cannot certainly call all dark academia ‘queer-bait’ — which is a marketing tactic used to garner the attention of queer audiences by using queer storylines or visuals to bait queer audiences without committing to accurately portraying the perspectives of actual queer individuals. However, the ways that the dark academia trend depicts queerness can be misleading in their ignorance of real queer experiences, reducing the hardship faced by these characters in books to an artificial aesthetic.

The dark academia aesthetic has taken the internet by storm, but it is important to understand why many queer readers resonate so much with it before you go on to engage with it as an aesthetic or a lifestyle — which is admittedly difficult when all that is shown to you is photos and online clothing store links.

So… now what?

With all that said, I don’t believe that those outside the queer community should pack their carabiners away into a dark corner; identity and self-expression are incredibly personal matters with widely varying experiential connections. If you’re moved to buy an article of clothing because of what you’ve seen online, you’re not necessarily contributing to any false narratives about any sexual, gender, or racial identities.

The normalization of dressing ‘gay’ should be seen as having a positive impact on the world of fashion. An issue arises only when the creators and history of queer fashion are being greatly overshadowed by consumerism and algorithms that don’t show the casual scroller what exactly they’re buying into, purely pushing the ‘aesthetic’ to make money. It’s almost an insult to dress this way and not know where it came from.

The queer aesthetics or notions of dressing ‘gay’ circulated by online platforms can be detrimental and disillusioning to the queer community. However, by taking a step back to try and understand the past and present significance of trends and online aesthetics, I hope that the average social media user discovers the ways that queer people have impacted popular style. Only then can we honour them while adding our own individual flair to help the genre expand.

Acknowledging the queer history present in modern fashion is an essential step into harnessing the power of social media trends like Pinterest aesthetics, turning them from artificial internet-made products into celebrations of diverse identities and self-expressions across queer and heterosexual communities alike.