If you have ever felt like you are being crushed under the weight of the future, you’re not alone.

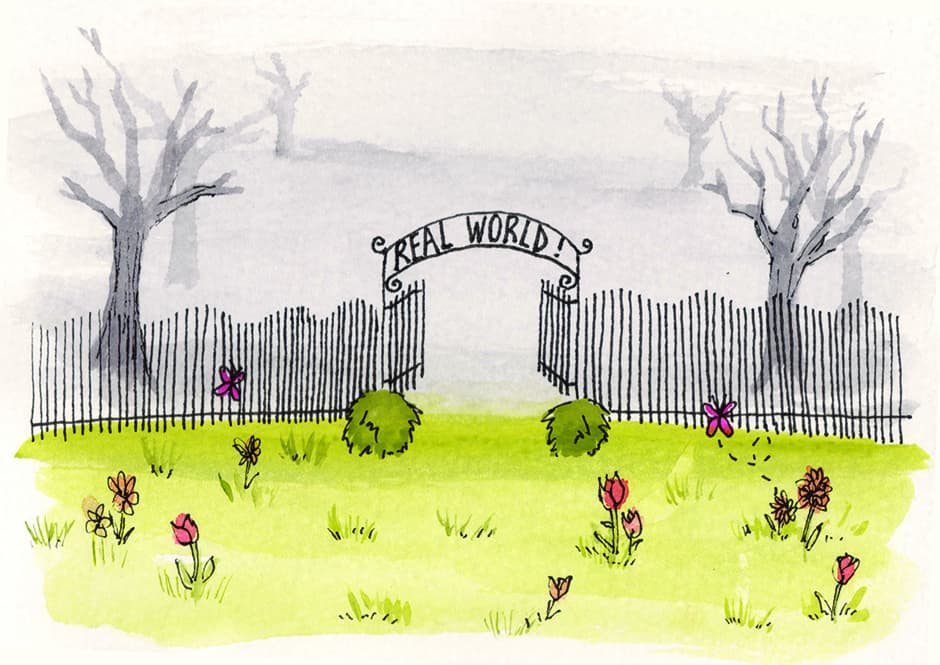

This feeling is among the first symptoms of a quarter-life crisis. You are trapped, either by too many options, or perhaps too few. The unpleasant condition strikes at the onset of entering the so-called real world, where we make decisions that will have massive consequences on the rest of our lives.

For some, the anxiety that comes with choosing the best possible path can turn critical. One wrong choice, and it seems like everything might fall apart.

As millennials, we can’t use our degrees as a universal passport like previous generations could, nor are we given a set of narrow expectations to work within. A career no longer guarantees lifelong employment under one firm. There are now many more decisions to be made in order to stake out a decent life, and much of that work begins while we’re still studying.

The hardest part, and also the most important, involves getting over the fear of regretting those choices later on.

For all of that, I feel paralyzed by the responsibility of having to plan the rest of my life when, in reality, my options are quite limited.

That’s something I share with the roughly one-third of U of T undergrads that received at least $15,000 in OSAP loans throughout their degree. This is on top of the growing need to supplement résumés with extra accreditation, simply to find work in a tough job market. Economic conditions have already determined a significant portion of our near future, whether we like it or not.

With a quarter-life crisis in full swing, I’m terrified that all this anxiety — not to mention the prospect of grad school and impending loan repayment — fritters away the scant amount of youth I have left.

Being in school often feels like a poor use of the energy, curiosity, and risk tolerance that is inherent to being a young person. Tied down to a loan, I’ll be well into adulthood before I ever get to backpack through Europe, build an off-the-grid home, or live on a farm in Chile.

The fear of future uncertainty is so widespread, there’s a group on campus that chooses to address it directly. Applications for Tertiary Education Realized (AFTER) U of T, an organization that helps students plan for future opportunities, holds events to promote the exploration of post-degree options.

It’s an excellent example of the kind of support systems one needs when they’re facing a crisis of choice. The group is unique in that it reminds students that they’re ultimately the masters of their own destinies, regardless of the restrictions imposed by debt and degree inflation.

Founder of AFTER U of T and second-year student Sasha Boutilier says that in his experience, students worry a lot about making good decisions, and often wonder if choosing university will be worthwhile in the long run. “The most common [anxiety] and one that really troubles me goes like something like this: I’m an English major, what if I just end up flipping burgers?” says Boutilier.

Boutilier has a rosy outlook on that uncertainty. He thinks that it’s a matter of optimism: building a future can be scary, but it’s also an exciting time, and we shouldn’t lose sight of that. Positive engagement with our choices will help us pick the best ones.

Researchers here at U of T are also helping students navigate the quarter-life crisis. Dr. Alison Chasteen, an associate professor of psychology, has reached a conclusion that supports Boutilier’s enthusiasm. In a recent study, she suggests that a sense of confidence about our future selves may positively influence our cognitive abilities in the present.

More surprisingly, she also notes that there might also be “psychological and functional benefits” to fearing lost opportunities. The very act of worrying about a possible future self who regrets past decisions is, according to Chasteen, “positively associated with personal growth.” It seems that if you frequently picture yourself middle-aged and remorseful, it may compel you to ensure that life doesn’t turn out that way. All our fear might be a good thing after all.

From the neurobiology perspective, U of T’s Dr. Will Cunningham recently co-published a study that considers well-being a subjective affair: satisfaction with life’s circumstance varies across individual experience. Whether you’re content with a savoury meal, or unhappy until you’ve built an empire, quality of life is hard to write a prescription for.

But whatever your personal definition of happiness, Cunningham’s analysis suggests a universal trait amongst satisfied individuals.

Cognitive flexibility, or the ability to view the same situation from various perspectives, is key to maintaining your well-being and deriving value from past actions, even though they may otherwise be tinged with regret. Keeping in mind that the brain is structured such that happiness is relative may allow us to see the sunny side of past mistakes.

Perhaps Cunningham’s study alleviates the pressures of the quarter-life crisis. But it’s not clear that we could willfully produce the kind of perspectival shift that cognitive flexibility requires. If you spend your twenties living in a basement apartment working three undesirable jobs, and end up missing career breaks because you opted to save for a down payment on a house instead, no amount of perspective will bring back those missed opportunities.

Attaining the sublime cannot be taken for granted. Well-being must be sought, doggedly and with an urgent concern for one’s future. A degree might open many doors, but some it inevitably closes. So think hard about your future, in as many dimensions that you can. Soon the merely imminent will be present, and then the present will be all you’ll have left.

Malone Mullin is a third-year philosophy specialist.