Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative condition that affects millions of people worldwide. This insidious and progressive disease has been implicated in many behavioural changes in cognitive functions: memory, comprehension, language, attention, and reasoning. While AD remains incurable, research has shown that certain factors may influence an individual’s susceptibility to the disease and the rate of cognitive decline.

One such factor in recent years is bilingualism. Bilingualism is not only a valuable skill for communication but has also been recognized as a protective factor in those at risk for AD.

Cognitive reserves and bilingualism

The term “cognitive reserve” describes the brain’s ability to withstand damage caused by aging or disease by optimizing neural functions. Studies suggest that individuals with greater cognitive reserve are more resilient and better equipped to cope with the cognitive challenges presented by conditions like AD.

A 2019 review by Mario F. Mendez, a behavioural neurologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, delved into the intriguing possibility that bilingualism may offer a form of protection against AD. Mendez’s research examined the complex bidirectional interaction between language skills and dementia, and found several studies that show bilingualism may delay the onset of dementia. A key idea emerging from this paper is that bilingualism may enhance cognitive reserves by engaging and strengthening various brain structures and connections.

This idea is supported by findings from a functional magnetic resonance imaging study that reveals notable differences in brain activity between monolinguals and bilinguals who became proficient in a second language early in life. Specifically, bilinguals who learned to speak two different languages from an early age demonstrated increased activation in language-related brain regions, such as Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area, which are responsible for language production and comprehension.

Bilingualism and cognitive reserve are fascinatingly intertwined. As the review highlights, studies have suggested that using two or more languages regularly can contribute to one’s cognitive reserve. This occurs because bilingual individuals engage in constant cognitive exercises as they switch between languages. In the case of bilingual AD patients, this increased cognitive reserve might manifest as a delay in the onset of dementia symptoms despite the progression of the disease.

Lastly, bilingual individuals with AD demonstrated better cognitive performance on various tests than their monolingual counterparts. Their ability to perform tasks related to language, memory, and executive function remained relatively stronger, further supporting the idea that bilingualism contributes to cognitive reserve.

Bilinguals’ frequent need to switch between languages and select the appropriate language for a given context appears to involve more extensive recruitment of the brain’s left hemisphere, which is generally responsible for language. This linguistic juggling act demands a higher level of neural activation, leading to significant differences in brain functioning between bilinguals and monolinguals. Such findings underscore the potential cognitive benefits of bilingualism.

Structural changes in the brains of mono versus bilinguals with Alzheimer’s

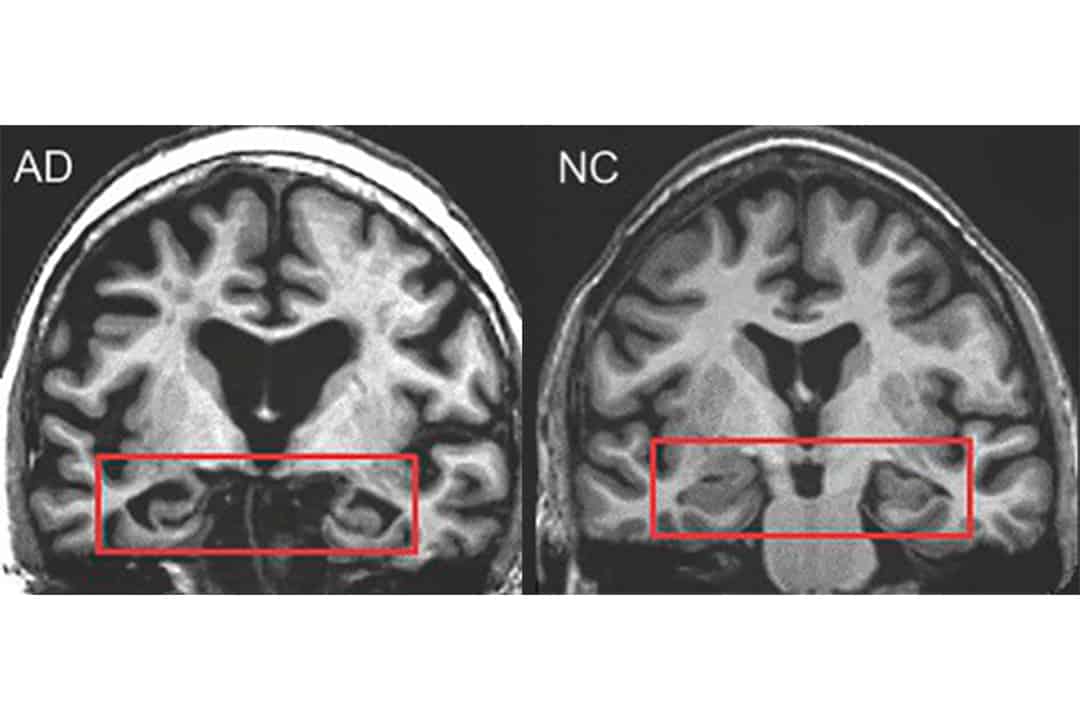

A study by Cyrus A. Raji and colleagues at Washington University, published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, presents compelling insights into the structural changes in the brains of individuals with AD, comparing monolingual individuals to bilingual ones. Their research involves the use of advanced neuroimaging techniques to examine brain volumes and structures.

The study reveals that bilingual individuals with AD exhibit a greater brain volume compared to their monolingual counterparts, even though AD is typically associated with brain atrophy and shrinkage. The larger brain volume observed in bilingual individuals suggests that they may have a greater cognitive reserve, allowing their brains to better withstand the effects of the disease.

The neuroimaging data also indicated differences in the structural changes within the brains of bilingual and monolingual Alzheimer’s patients. Bilinguals showed more preserved brain regions associated with language and executive function. These regions are vital for memory, problem-solving, and decision-making, all of which AD significantly impacts.

The research supports the concept of cognitive reserve, emphasizing the importance of engaging in cognitive exercises such as language switching, which bilingualism inherently involves.

While bilingualism is not a guaranteed shield against Alzheimer’s, it may contribute to building cognitive resilience and delaying the onset of cognitive decline. This research highlights the potential benefits of bilingualism beyond linguistic and cultural advantages and underscores the importance of continued exploration in the field of neurology and cognitive science. So, in the quest for mental fortitude, embarking on the journey of learning a new language sooner rather than later might just be your brain’s best bet!

No comments to display.