What does it mean to be in love?

Is it a chemical reaction? An undefinable experience? Or, as one 2016 scientific paper from Sri Ramachandra University describes it, “an emergent property of an ancient cocktail of neuropeptides and neurotransmitters?”

To me, understanding any type of love only through the chemicals produced in the brain feels unsatisfying. After all, isn’t there something to be said about the subjectivity of love?

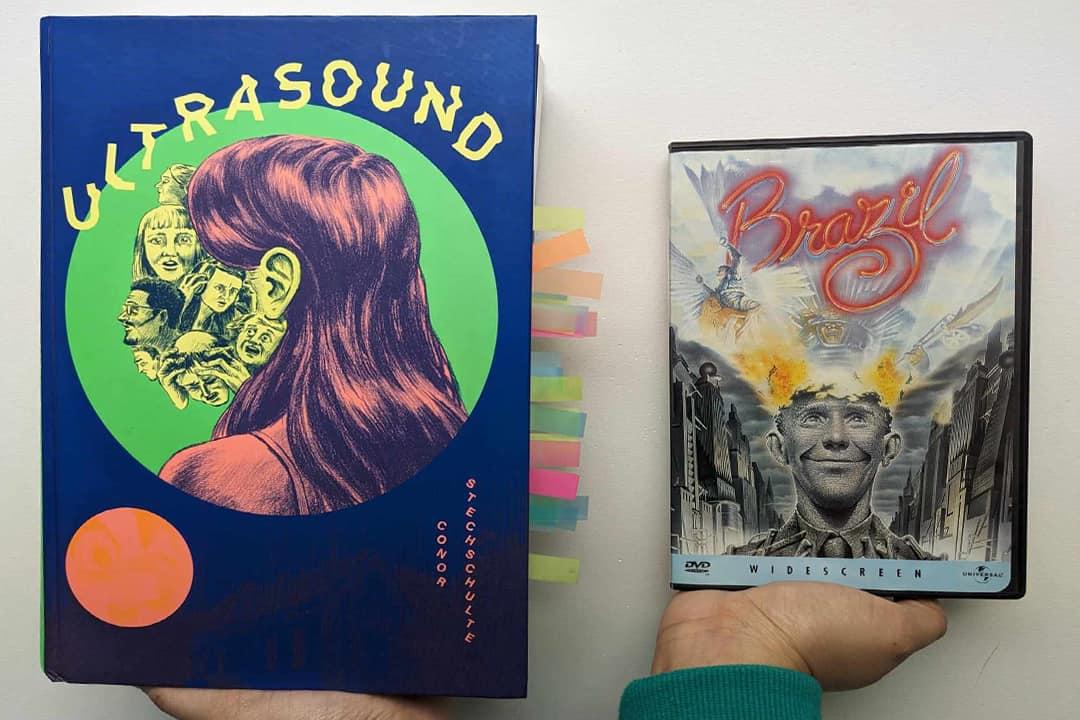

Oliver Sacks’ nonfiction book Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain, Conor Stechschulte’s graphic novel Ultrasound, and Terry Gilliam’s film Brazil all feature cases of people or characters who continue to love in the face of memory loss or alteration. These cases discuss all the subjective aspects of love or affection and how they’re able to persist in situations we wouldn’t expect.

The curious case of Clive Wearing

Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain by neurologist Oliver Sacks describes Clive Wearing, a real-life musician and severe amnesiac who still remembers his love for his wife, Deborah, and for music.

In the ’80s, Wearing acquired a brain infection called herpes encephalitis, which left him with a memory span of a few seconds. Despite this, Sacks describes him recognizing and finding great comfort in Deborah, although he couldn’t remember their time dating. He also could play pieces on the piano with the intensity and emotion of his pre-amnesia years, a sign to Sacks that Wearing’s case said something unusual about the way we remember music.

Early on in the chapter, Sacks makes the important distinction between semantic memory, episodic memory, and procedural memory. Semantic memory is knowledge of facts and other data, essentially knowledge about something like an event or object. Wearing retained this to an extent and could hold scattered but still enthusiastic conversations about topics he was interested in.

Episodic memory is what structures procedural and semantic memory; it is the memory of events and lived experience, and the part of Wearing’s memory that is highly compromised due to damage to his hippocampus and temporal lobe structures. The temporal lobe is responsible for our ability to process language, emotions, memory, and sensations. The hippocampi transfer short-term memories into long-term storage, which is what makes them so important in the study of long-term memory loss.

Wearing’s episodic memory was so damaged from his infection that he was unable to retain events for more than a few seconds, and couldn’t remember most people consistently aside from Deborah, his grown-up children, or his grandchildren.

Procedural memory, the memory of performing tasks, Sacks describes, involves “larger and more primitive parts of the brain” such as “subcortical structures… and their many connections to each other and to the cerebral cortex.” It is easier to retain procedural memory than episodic memory in the face of amnesia, as subcortical structures are large and diverse, making them less likely to all get seriously damaged. This explains why Wearing could still dress himself, dance, brush his teeth, and play the piano.

What drew me to Wearing’s case was not its reinforcement of the distinctions within memory but rather the fact that he retains a deep love for his wife, who in turn shares his love for music. To Sacks, it seems that there is a connection between the profound emotion he experienced for Deborah and his sustained ability to play music with a similar level of emotion — this wasn’t just procedure or facts he was retaining, but a deeper feeling.

Conor Stechschulte’s Ultrasound on the effects of emotion on memory

In the graphic novel Ultrasound (2022) by Conor Stechschulte, the protagonist, Glen, finds himself stranded with a flat tire in the middle of a storm. He knocks on the door of a couple, and eventually agrees to have sex with the wife, Cyndi, so that the husband feels more secure in having taken care of her despite his depression.

The novel immediately makes it clear that things are amiss. When Glen tells his friend about the event, his friend contests the idea that it was raining that night, and in a flashback to the night, we see that Glen’s car had a flat tire because it ran over nails. The faces of certain people are smudged over in panels that are supposed to relay memories of what happened, and entire pages of the novel are covered in lines of rain or smudges that obscure the words on the page.

Unlike Wearing, Glen is not an accidental amnesiac. As the plot develops and Glen’s memory becomes increasingly contradictory and obscured, we learn that Glen is unwillingly part of a mind control experiment. Under hypnosis, Glen can be told to take a random action, and when snapped out of it, he will construct a story to make sense of that action.

By the end of the story, it is clear that Glen and Cyndi’s relationship is fabricated, if not through hypnotic suggestion then through the lies and trickery of everyone around them. Yet Glen seems to hold affection for Cyndi, even while knowing that his own memories are unstable and unreliable.

In Ultrasound, Glen’s episodic, and in some cases procedural, memories are forcibly destroyed, but there is some emotional memory to which his brain clings. Here we see a bleak mirror of Wearing; despite his degraded memory, Glen retains enough emotional memory to still care for Cyndi.

Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, an epilogue on imagination

The movie Brazil (1985), directed by Terry Gilliam, also plays with the ideas of memory and love. Brazil is set in a futuristic totalitarian society. It is centred around a low-level government official, Sam Lowry, who sees a woman from his dreams named Jill in real life. He chases her around the city, driven by curiosity and his increasingly disturbing dreams.

As the movie goes on, Sam’s imagination and reality blur, leaving us to question the true relationship between Sam and Jill. Jill is often there and then not; her appearance and existence in the government’s system are as transient as Sam’s dreams of flying toward her with mechanical wings.

Is Sam’s episodic memory reliable here? Can his bearing on reality tamp down on his deep emotional commitment to imagining an escape with Jill? Sam’s imagination is also similar to amnesia — his ability to distinguish between what is memory and what is constructed becomes completely destroyed by the end of the movie. And yet, his emotions remain.

In all three of these cases, then, we see how emotions like love can persist despite memory degradation.

In a footnote, Sacks recounts a passage in Umberto Eco’s novel The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana where the narrator hums a tune and yet forgets it as soon as he starts thinking about it. The narrator says that he is “living in pure loss” — but Sacks calls that same situation living in “pure gain.” Sacks writes, “The song almost miraculously seems to create itself, note by note, coming from nowhere — and yet… we contain the entire song.”

Sam’s story, his life in that totalitarian society, could be seen as the classic modernist defeat of man. But despite it all, Sam ends up smiling, humming “Aquarela do Brasil,” note by note.

No comments to display.