“Everybody has an opinion about language. Everybody observes language,” Professor of Linguistics Sali Tagliamonte tells me as we sit in her sunlit fourth-floor office in the Sidney Smith building on St. George campus. “And as a language scientist, you’re constantly like, ‘Yeah, right, why would you want to listen to me? I’m the one who studies it.’ No — no one believes us!”

It is less an exclamation of exasperation than a kind of exuberant incredulity. “It’s a great time to be a sociolinguist,” she says.

As part of Canada’s sesquicentenary, a team of professors and graduate students at the U of T Department of Linguistics, including Tagliamonte, has charted the changes in language in Toronto over the last century and a half.

The group has organized a series of three workshops over the course of the year, which are designed to explore language change in Toronto and promote broader awareness and discussion of a topic that Tagliamonte says “everybody is interested in… And everyone talks about.”

In conjunction with this program, a pop-up exhibit from the Canadian Language Museum titled Canadian English, Eh? will offer a broader, cross-Canada view of language change over the course of our country’s 150 years.

Toronto’s heritage languages

A forthcoming workshop entitled “Toronto Language Tapestry: Exploring Heritage Languages” will take place this Friday, April 28 at Woodsworth College. Organized by U of T Associate Professor of Linguistics Naomi Nagy, the event will consist of a series of presentations by researchers who have been investigating the shifts in the heritage languages spoken by first- and second-generation Torontonians, such as Italian, Cantonese, and Polish.

The range of languages spoken in Toronto is staggering. More than two million residents’ home language is neither English nor French, Canada’s two official languages. Diversity “makes for an interesting laboratory for people who study language,” says Tagliamonte. Her colleague Nagy emphasizes that the melting pot of the Torontonian cultural tapestry may be forging entirely new dialects.

“Italian has been spoken in Toronto for a hundred years,” she says. “Now, it seems possible that we’re developing a Canadian dialect of Italian. And so to see if that’s true… we’ve been recording speakers of different generations — immigrants, children of immigrants, grandchildren of immigrants — and looking at whether there are differences in their pronunciation or their grammar or their vocabulary.”

Highlighting changes

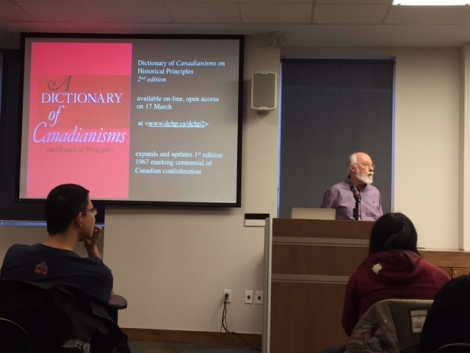

The first event of the sesquicentennial workshop series introduced the theme of language change in Toronto. Titled “From Quaint to Cool: 150 Years of Language Change in Toronto,” the event was held on March 3 at the Jackman Humanities Institute. Topics spanned Confederation-era Toronto English to the movement of social media slang into everyday speech in the present day.

Tagliamonte, an organizer of this event, emphasizes the magnitude of language change in Toronto since the nineteenth century. “‘From Quaint to Cool’ is exactly what has happened. We have gone from Victorian English and Canadian Dainty, where people had British accents, right down to the GLBQ phenomenon going on today,” she says, referencing the debate around heteronormative biases in language and gender pronoun identification that has ignited a firestorm of controversy at U of T and elsewhere.

Language change is both an indisputable and mysterious phenomenon. As with biological evolution, subtle processes of gradual, cumulative change lead to new words and pronunciations that share few similarities with their predecessors. The differences between the late-fourteenth-century English of Chaucer and the English of the present day bear testament to the dramatic shifts that punctuate any language’s history; they are reflections of the ever-changing cultures that speak them.

“It’s a great time to be a language scientist, because… language change keeps apace with sociocultural change,” Tagliamonte says. “And so if you think of the twentieth century, it’s amazing how much change has gone on… 1991, when the World Wide Web goes online, things explode after that in terms of social contacts and interactions in multi-dimensional global world communication… Before most of my students have breakfast they’ve already had a conversation with someone in another country, let alone the neighbours down the street.”

‘Tronna’

Our city’s name serves as an interesting example of language change. Both the first ‘o’ and the second ‘t’ in Toronto are subject to deletion based on the speaker, creating variants that carry cultural information. Formal speech, such as that of an American sports announcer covering a Leafs-Penguins hockey game, tends to accentuate the consonants —‘Tor-ON-toe.’ This variation is generally mocked by native Torontonians, who take pride in trimming the primness of that second ‘t’ to produce ‘Ta-raw-no’ or ‘Tronna.’

Both variants are often used in exaggerated fashion by non-Torontonian Canadians to poke fun at a city that itches for an accent and the individualism that comes with it — think Boston, for example. “When we’re trying to imbue words with sociosymbolic value, they often undergo those kinds of processes,” Tagliamonte notes. One wonders if Calgary and Halifax might be undergoing similar sound changes, to ‘Caw-gree’ and ‘Ha-fax.’

Simplification or reduction of word sounds appear to be the dominant mechanisms at work in such a shift. Like a pencil tip being whittled down with use, words used with higher frequency in language tend to undergo processes of weakening, shortening, and deletion that permanently change the word in question. The middle vowel in a commonly-used word like ‘every’ is more likely to be dropped than in lower-usage words such as ‘wintery’ or ‘memory.’ Consonant deletion is apparent in the many high-frequency English words that begin with the consonant cluster ‘kn’ but that are today pronounced without the hard ‘k’ — ‘know’ and ‘knife,’ for example.

Understanding dynamism

There are many interesting histories and idiosyncrasies to the words we use so freely today without second thought. Because language change is so gradual, it is difficult for most speakers to recognize the dynamism and pliancy of the spoken and written word, which contain our history and our future. The events organized by the department seek to address this gap in our awareness about perhaps our most important tool as humans.

“One of the things we would like to share and celebrate is the fact that language is an amazing thing,” says Tagliamonte. “That’s part of who we are as human beings.”

Language is a useful criterion in examining the way a community or city’s cultural coherence and collective thought processes change over time. As such, symptoms of generational divides inevitably emerge when tracking changes and shifts in the written and spoken word.

Nagy notes that parents often criticize their children for not speaking their heritage language with enough frequency or proficiency. As a result, younger generations use English more because “in many cases, their English is better than their parents’ and their grandparents’ English… so it’s kind of much safer for them.”

When English becomes the default, heritage languages risk a decline into obsolescence. But instead of disappearing, they may also morph into new dialects, as noted above with the example of a distinct Canadian-Italian dialect. It is a development that Nagy acknowledges is contentious among older-generation speakers even as it is extremely fascinating to linguists.

“Part of the goal of this project is to understand how languages change, but another part of it is to try to help the communities where these languages are spoken to understand that languages do change… When a language has fewer speakers, change can be very scary for the people where that language is an emblem of their whole culture,” Nagy says.

Tagliamonte adds, “When you look at language, you’re not just looking at a complex, adaptive system that is rich in systemically shifting parts… We’re also looking at something that operates in a social world, with interactions and people and prestige and identity.”

Speakers who identify closely with their native language and recognize peers in their community based on sociolinguistic cues are untethered when the mainstay of their culture changes across generations.

Canadian Indigenous languages

The third workshop in the linguistics series will take place this autumn and will focus on changes in Canadian Indigenous languages across time, taking on a broader view that includes many Indigenous communities. “As we go back in time, we can grow in the geographic scope that we can look at,” Nagy explains.

This is a particularly important component of the project. Of the more than 60 languages spoken by our country’s Indigenous groups, as recorded by a 2011 Canadian census, only a few — such as Inuktitut, Anishinaabemowin, and Cree — are expected to survive.

Marginalized identities and dialects are being lost completely with the onward march of globalization. One need only look at the legacy of Canada’s residential schools, whereby entire Indigenous languages have been lost through the government’s program of assimilation and systemic eradication of these groups’ cultures.

In his Course on General Linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure writes that “without language, thought is a vague, uncharted nebula.” Tracking how language changes through the maelstrom of human expression is an important project in mapping the “nebula” of cultural thought and identity across its many dialects — and, as Tagliamonte notes, understanding what it means to be human.

The next event in the series, Toronto Language Tapestry: Exploring Heritage Languages takes place on Friday, April 28, 2017, 12–5 pm at Woodsworth College, Room 126.