The repeated use of closure by the federal Conservatives to end parliamentary debates has triggered a firestorm of controversy leading many to question the government’s commitment to democratic principles. As the Globe and Mail observes, the Harper conservatives have invoked closure more frequently than any previous government. It has been used to end debate on everything from the long-gun registry, to the Wheat Board, to adding more seats to the House of Commons. Criticisms range from Pat Martin’s colourful Twitter rant about the closure of debate on the budget to the more even-tempered comment by human rights lawyer and former Attorney General Irwin Cotler that the government’s use of the device to push it’s omnibus crime bill through second reading amounted to “a hijacking of democracy.”

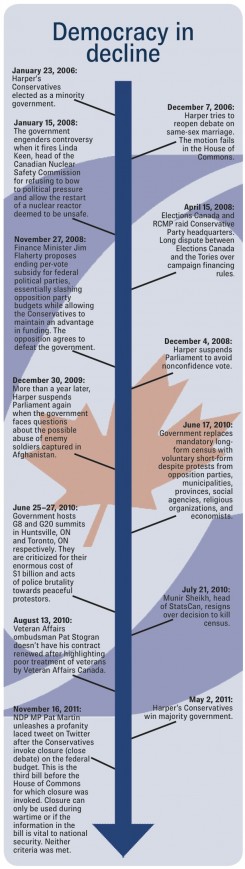

Claims that the government’s actions are authoritarian and contrary to the democratic spirit are certainly correct. A healthy democracy requires that voices be heard, and dissent tolerated. Elizabeth May’s description of the repeated closures as “a stunning assault on democracy,” however, is only half-correct. Anyone who is stunned that Harper’s Conservatives would assault democracy has not been paying much attention to Canadian politics over the last five years. A brief review of their track record on this issue proves informative.

After taking office in 2006, one of the Harper government’s first official acts was the placement of sharp and unprecedented restrictions on the parliamentary press gallery. This has drastically decreased governmental transparency. The move touched off what CTV described as a “battle between a PMO seeking total message control and news media defending their hard-won access.” Harper spokesperson Sandra Buckler dismissed media concerns about the holding of secretive cabinet meetings and the pre-screening of questioners by claiming that average Canadians didn’t care about the lack of transparency “as long as they know their government is being well run.’’ However, she did not exactly say how they were supposed to know this despite carefully managed press access. Geoff Norquay, a close adviser to Harper, was a little more forthright explaining that the PMO wanted to “keep a tight lid on its messages,” as Harper had learned from the example of his predecessor, Paul Martin, who was too transparent for his own good.

Shortly after restricting the press gallery, the Conservatives made clear their position on another pillar of democracy: minority rights. When the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was adopted by the Human Rights Council in 2006, in response to the “urgent need to respect and promote the inherent rights of indigenous peoples,” the newly elected Conservatives opposed it vigorously, working with New Zealand, the US, and Australia to obstruct the process. The Conservative Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development called UNDRIP “unworkable in a Western democracy under a constitutional government,” and Canada alone among Human Rights Council members opposed the declaration at the general assembly. It seemed that the Conservative rejection of UNDRIP was another attempt to evade responsibility for the crushing poverty in which much of Canada’s indigenous population live and they had reneged on a pledge by the previous government to provide development funds the same year. A statement on the government’s website, however, explained that the real reason was that “Canada wanted to build a broader consensus” for the declaration at the general assembly, as a vote of 143 to 4 in favor fell short of quorum in the Conservatives’ view.

Moving on to 2008, the government made its first attempt in what would be an ultimately successful bid to eliminate a democratic form of political party funding while keeping an undemocratic one under the guise of strengthening democracy. When Conservative Reform Minister of State Stephen Fletcher argued that the per-vote subsidy must be eliminated to protect voters from being “forced to make involuntary contributions based on parties (election) results” the three other major parties, recognizing that they would have their funding slashed while the Conservatives continued to enjoy publicly-subsidized donations from their wealthy constituents, unsurprisingly moved for a vote of no confidence in the minority government. Harper defied credulity in his attempts to paint the non-confidence vote — a parliamentary check against executive power — as a “backroom deal” by Stephane Dion, whom he accused of trying to “take power without an election.” The spin campaign failed, and with his government on the brink of defeat, Harper shut down Parliament to buy his party time. The first prorogation was a success, as the Conservatives weathered the storm and stayed in power. The cost to the taxpayer was in the tens of millions, along with, of course, the lack of governance for nearly two months.

Although Canadians were enraged by the contempt for democracy inherent in the prorogation of 2008, the government was again shut down just over a year later. In this case, the Conservatives were facing embarrassing pressure to release documents regarding the Canadian military mission in Afghanistan. Release of the documents was demanded after credible allegations arose that Canadian government and military officials had been turning a blind eye to the transfer of prisoners, by Canadian troops to security forces, which had been using torture as an interrogation tactic — a practice that would violate the third Geneva Convention. Harper responded to the allegations by saying that Canadians didn’t care whether or not the government was covering up the alleged torture of detainees, which ranged from the use of knives and electricity to sexual assault. “That’s not on the top of the radar of most Canadians” he said at the time. “What’s on their radar is the economy.” Once again, Harper prorogued Parliament to buy time for this issue to blow over — at a cost of roughly $130, 000, 000, and 22 days of governance. That brings us roughly up to date. Although the review is by no means exhaustive, it should give Canadians cause to consider the level of our government’s commitment, if any, to democratic principles. So should the words of a young Stephen Harper, written almost a decade before he was Prime Minister.

In 1997, at the beginning of his political career, Harper penned a now-famous essay in which he complained that the Canada’s political system was badly broken. With the Conservative party fragmented and weak, a string of Liberal electoral victories had resulted in a “one-party-plus system” which was, he assured the reader, “little better than a benign dictatorship.” One can think what one likes about this characterization, but assuming that Harper really believes that the repeated winning of fair elections by a political party constitutes some kind of dictatorship, then how would he describe a government which silences debate, carefully manages press access, rejects minority rights, defunds its opposition, and suspends Parliament at its convenience? One shudders to think.