Tommy Jardine, 61, is about to arrive in a new city for a new job. Tommy is from Miramichi, New Brunswick, where he lives with his wife on the homestead his grandfather built in 1920 after emigrating from Boston.

For 30 years, Tommy worked in an iron ore mine in northern New Brunswick until it closed in 2000. To support himself and his wife, he has spent his summers working in construction and his winters plowing snow. Today, he will land in Fort McMurray, Alberta. He’s boarded a bus at the airport, along with a dozen other men, which will take him to an oil sands worker’s camp where he will live and work for the next four weeks. He doesn’t yet know what his job will entail.

[pullquote]Shortages in the Albertan labour market have driven wages up — the average household income in Fort McMurray rose to $177,634 last year.[/pullquote]

“When the mills and mines closed, a lot of families sold their homes and left town,” Tommy explains through his thick northern New Brunswick accent. “A bunch of the younger guys have gone to work in the Alberta oil patch. We keep losing industry, and they’re gonna have to leave. People are hurting.”

Miramichi was hard-hit by the recent recession, but the local economy had been in decline since the 1970s. The search for employment has driven Miramichi-dwellers elsewhere, and many of them are choosing Fort McMurray. A 2011 survey found that more than a quarter of travellers leaving from the nearby Bathurst airport were headed there. The total income earned by migrant workers from New Brunswick alone in the oil sands boom is estimated to be between $230 and $350 million.

“When the boom word comes up, there’s an opposite cycle that says ‘bust,’” says Melissa Blake, the mayor of Wood Buffalo, the regional municipality into which Fort McMurray was amalgamated in 1995. Sitting in her newly renovated office on the seventh floor of the municipal government building overlooking downtown Fort McMurray, she explains, “The difference that I see between a boomtown and sustainable growth is that we’ve been experiencing this growth since about 1996, and it doesn’t look to end in the future.”

The municipality’s population growth projections are based on this assumption of sustained long-term growth, a forecast of increases in oil sands output. By 2030, the population is projected to more than double to 225,000, over 85 per cent of which will reside in Fort McMurray.

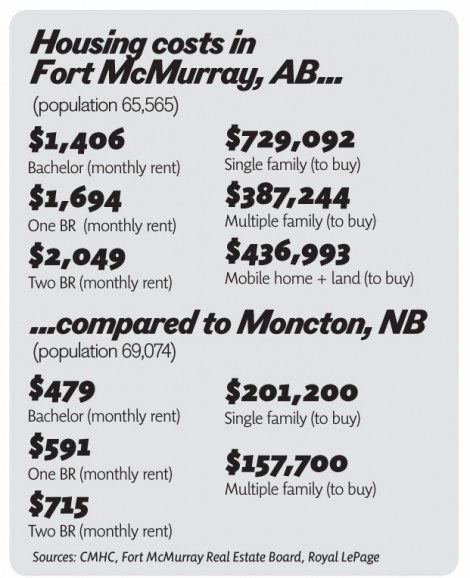

The cost of housing in Fort McMurray is astronomically high. Almost every parcel of available land has been developed, and the outskirts of the city are densely packed by cheaply built pre-fabricated homes, low-rise apartments, and motels. Cars are the preferred mode of transport in Fort McMurray, and it shows. Public transit, recently expanded, sees little use. Most of the city’s population lives several kilometres from downtown in communities branching off from the arterial Highway 63.

The cost of housing in Fort McMurray is astronomically high. Almost every parcel of available land has been developed, and the outskirts of the city are densely packed by cheaply built pre-fabricated homes, low-rise apartments, and motels. Cars are the preferred mode of transport in Fort McMurray, and it shows. Public transit, recently expanded, sees little use. Most of the city’s population lives several kilometres from downtown in communities branching off from the arterial Highway 63.

At all hours of the day, the highway, which runs through downtown Fort McMurray, is abuzz with dirt-caked buses and trucks carrying workers and equipment to and from the oil sands. Driving along the highway, you can see the signs of industry, with sales offices for manufacturers of heavy equipment lining either side.

Further north, before reaching the main extraction and processing sites, the smell of gasoline and sulphur permeate the air. Depending on wind patterns, the smell can blow into the city, some 30 kilometres to the south.

The scale of industrial change is difficult to assess until the highway splits in two, when the boreal forest gives way to the barren, windswept landscape of the tailings ponds. The skyline is illuminated by a four kilometre-wide Suncor processing facility with a gas flare tower topped by a huge flame that burns off excess gas from the production process. The vapour plumes from the site are visible for miles.

Melissa Blake, mayor of the regional municipality of Wood Buffalo, home to 104,338 people, works in her office in downtown Fort McMurray.

Around the base of this installation, and others in the area, are the lodgings of over 30,000 workers. Like Tommy Jardine, they will work rotating shifts around the clock to ensure the uninterrupted extraction and production of bitumen.

A standard 158-litre barrel of crude oil takes two metric tons of extracted and processed bituminous sand. As of late last year, the total output of the Athabasca oil sands was over 1,700,000 barrels of oil per day, and is projected to triple by 2030.

This explosion in production will doubtlessly bring new waves of migrant labour to Fort McMurray. In the next eight years, over 13,000 new workers will be needed in the oil sands alone. Shortages in the Albertan labour market have driven wages up — the average household income in Fort McMurray rose to $177,634 last year.

The high wages have attracted thousands of temporary labourers. A sharp drop in the price of oil, like the one experienced in the 2008 recession, would lead to the cancellation or postponement of many capital projects. Many migrant workers would find themselves out of work, forcing them to return home.

One of the biggest challenges Fort McMurray faces is the integration of these transient workers into the community. Still, Mayor Blake doesn’t agree with observers who say the city’s population is largely transient.

“A lot of people would be rumoured to come with a two-year plan, make some money, and then vacate,” says Blake. “But they become so enamoured by the community and the lifestyles they’ve been afforded here.”

Fort McMurray’s community has had substantial support from the oil companies operating in the region, she argues. “You’re going to find [oil] industry names across a number of different community projects, but that’s not where [their involvement] ends. They’re also great contributors to the non-profit sector.”

When asked whether he’d stay in Fort McMurray, Tommy is not so certain he would.

“If there was an economy back home, I’d be there. I grew up in Miramichi. My grandkids grew up there. It’s home.”

Text and photos by Matthew D.H. Gray