Good things do sometimes come in small packages at the ROM. Although the massive exhibit “Ultimate Dinosaurs: Giants from Gondwana” is currently receiving most of the limelight, a new and much more innovative exhibition has popped up in the First Nations gallery. It is called “Sovereign Allies and Living Cultures: First Nations of the Great Lakes.” Although its name is a bit of a mouthful, this tiny exhibit provides an innovative and intelligent look at First Nations perspectives on the War of 1812.

Commemorations of the War of 1812, in its bicentennial this year, too often overlook the crucial role that First Nations groups had to play in this historic battle between Canada and the United States. Dr. Trudy Nicks, the curator of the “Sovereign Allies” exhibit, felt that the time had come to make some of their stories heard. As she walked with me around the single glass case that houses the exhibition, Nicks spoke eagerly about the thought that went into each carefully chosen artifact, and the significance behind this novel exhibition.

Commemorations of the War of 1812, in its bicentennial this year, too often overlook the crucial role that First Nations groups had to play in this historic battle between Canada and the United States. Dr. Trudy Nicks, the curator of the “Sovereign Allies” exhibit, felt that the time had come to make some of their stories heard. As she walked with me around the single glass case that houses the exhibition, Nicks spoke eagerly about the thought that went into each carefully chosen artifact, and the significance behind this novel exhibition.

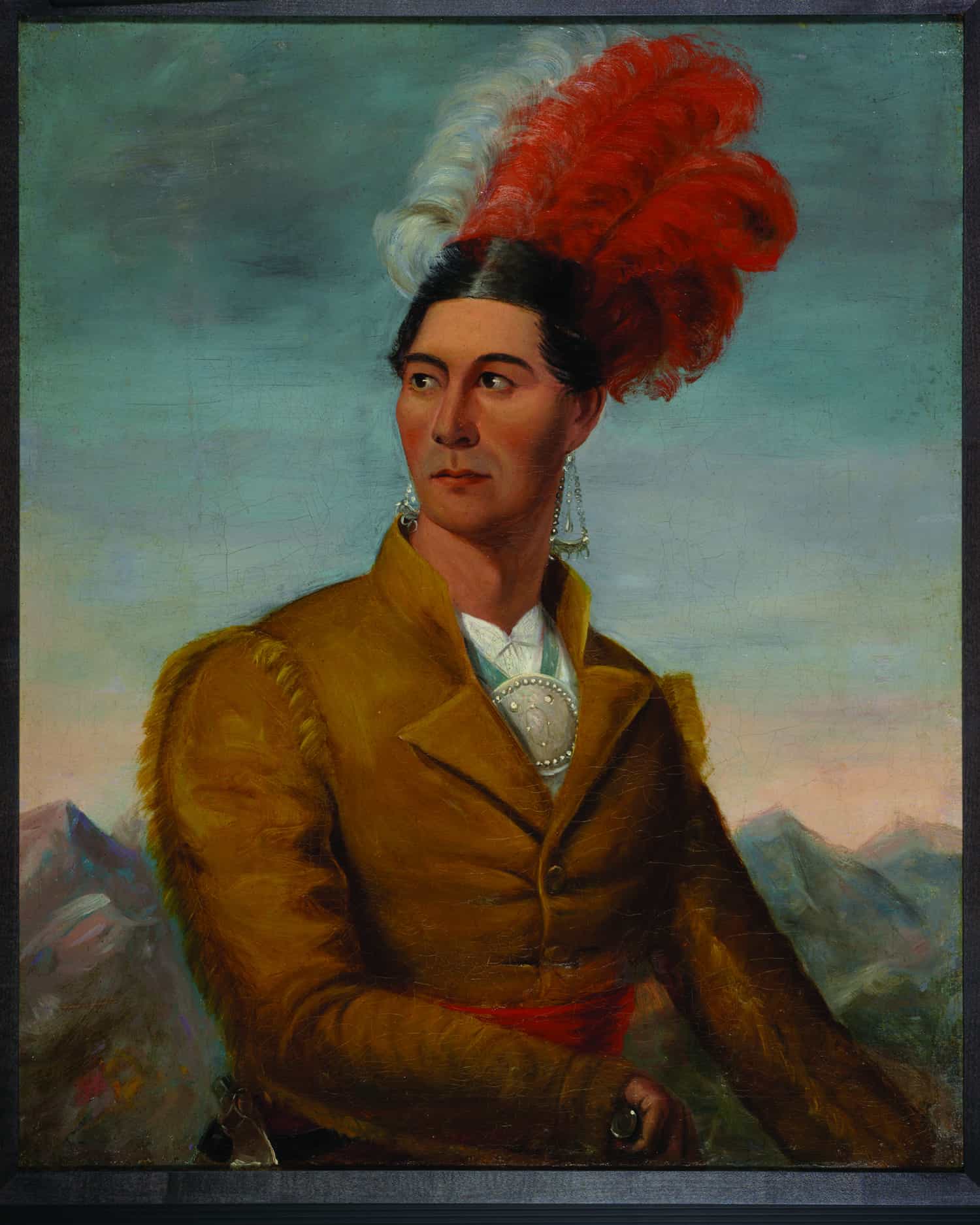

According to Nicks, “the objects and collections [in the exhibit] represent important stories and histories,” and as a result, she wanted to let the artifacts in the collection speak for themselves. The stories of six influential but lesser-known Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe war leaders thus became one of the main focal points of the exhibit. The array of artifacts attributed to these men is diverse and telling; each object speaks volumes about its owner’s stature and the respect given to him by the British.

The choice to focus on these particular war heroes — John Norton, John Brant, John Smoke Johnson, Oshawana, Wabjijig and Shingwaukonse — instead of the more famous Tecumseh, was intended to illuminate the important but little known roles that these men played during the War of 1812.

But Nicks’ main objective in creating this exhibit was perhaps to highlight the true nature of the relationship between the First Nations and the British during the war. As the title of the exhibit suggests, their interaction was very much a meeting of two allies — two sovereign nations.

Nicks was quick to point out that the assortment of medals and adornments in the exhibit that are made from silver, a metal that has significant spiritual significance to First Nation peoples, embodies this reciprocal relationship and highlights the mutual respect between the First Nations heroes and the British.

“What’s important to remember is that the Native people were fighting for their own lands, not for the glory of the British,” she said.

The rest of the display is devoted to the “Living Cultures” aspect of the exhibition, which aims to debunk stereotypes about what it means to be an aboriginal person in Canada. The first work in this piece is by far the strangest: a diorama of a Mohawk family that was previously banished to the basement of the ROM in 1970, and has now been re-imagined with the three members holding an iPod, power drill and camera respectively, while dressed in traditional clothing.

According to Nicks, this installment represents exactly what the rest of the “Living Cultures” component of the exhibit seeks to demonstrate: the mingling of traditional and modern that defines First Nations life today. It reminds the viewer that First Nations’ traditions and ceremonies are still very much alive, but that the people who practice them are not stuck in the past and are very much looking forward to the future.

This fresh perspective on the history of First Nations people in Canada is a welcome respite from other displays in the gallery, which depict the practices of indigenous peoples in the past but fail to acknowledge the progression of their culture into the present.

The words of a former chief of the Assembly of First Nations, inscribed on a plaque on the diorama of the Mohawk family, perfectly captures the First Nations’ desire to alter the current perception of their culture: “We do not want to be depicted the way we were, when we were first discovered in our homeland in North America. We do not want museums to continue to present us as something from the past. We believe we are very, very much here now and we are going to be very important in the future.”

Hopefully, “Sovereign Allies and Living Cultures” is the first step in making this vision a reality.