University athletic recruitment has become a very serious business. While U of T is renowned for its academic prowess, student athletes contribute to an athletic culture that has also played an important role in the university’s long and illustrious history.

Swimming

Recruitment, according to Byron MacDonald, head coach of the Varsity Blues swimming program, depends first and foremost on a strong academic record.

“I look for smart swimmers,” says MacDonald, “They will not gain acceptance to U of T [otherwise], or won’t stay in [the program] if they are not good students.”

U of T’s swimming program has a long history of success dating back to the 1950s, and the Blues continue to be a competitive team. “The program attracts some of the top swimmers in the country and is a bona fide developer of elite world-class athletes for Canada,” asserts MacDonald.

U of T’s swimming program has a long history of success dating back to the 1950s, and the Blues continue to be a competitive team. “The program attracts some of the top swimmers in the country and is a bona fide developer of elite world-class athletes for Canada,” asserts MacDonald.

The men’s team has won the OUA title nine years in a row. “In fact, Toronto has never finished below [second-place] in the conference, ever,” notes MacDonald.

The women’s team has shared similar success, ranking within the top three of standings throughout the past three years.

To make the Blues swimming team, swimmers must be able to swim fast. “A beautiful stroke is meaningless if they swim slow with all the beauty. They have to be able to swim at a certain speed,” MacDonald emphasizes. “If they can’t swim that fast, they can’t even try out for the team as they will never make it.”

Swimmers must also come from a club background where they have swum competitively for years. “This is not a sport or team that you take up seriously in university if you have not done it before,” stresses MacDonald. “Not at U of T anyway.”

Someone who is a good high-school swimmer, but who has no club experience does not have the necessary training to make U of T’s team, whereas for most other university teams in Ontario, a good high school swimmer would be able to swim at the university level.

Students who are not fast enough are told to improve their times with the masters or triathlon teams on campus, and to try out for the team the following year. “But I am pretty straightforward that the odds of that happening are very unlikely,” says MacDonald.

“Walk-ons usually will make [most of the other teams in Ontario but] they won’t make our team.”

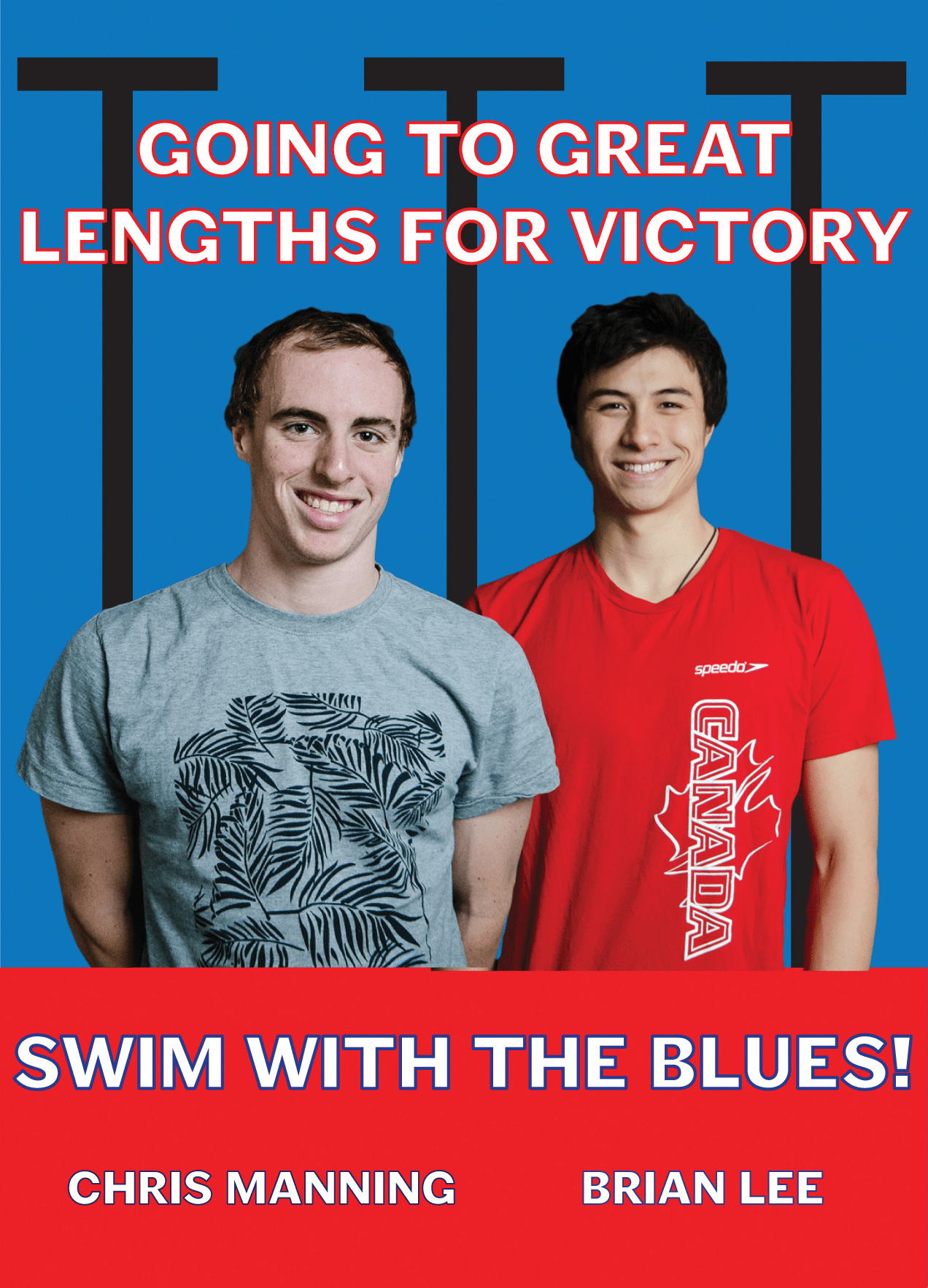

Chris Manning is a third-year history specialist. Manning swam at Auburn University south of the border for two years before transferring to U of T. He began swimming competitively when he was 10 years old, qualified for the Olympic Trials at age 15, and broke the national age group record in the 50m free swim in both short and long courses at 17. He is also a multiple medalist at the Canadian Senior Nationals, and hopes to qualify for the 2013 World Championships in Barcelona.

“To find success, one must fully commit to all aspects of the sport including nutrition [and] recovery in addition to the training,” Manning says.

Manning’s teammate, Brian Lee, is a second-year philosophy major. Lee has swum competitively for the past 13 years, medalling at the provincial, state, and national levels in Canada and the US. He hopes to win a gold medal at the CIS championships, which will qualify him for the World University Games.

Earlier in November, Lee helped lead the Blues to victory over both Brock and Waterloo, with wins in the 50m and 100m freestyle competitions.

Lee also has advice to share with aspiring athletes. “Be sure it’s something you really want to do, and that you like the team and coaches,” he says. “There’s nothing more miserable than dedicating half your time and energy to something you aren’t enjoying.”

Basketball

Like swimming coach MacDonald, Michael DiGiorgio, the assistant coach of the men’s basketball team, spends much of his time searching for developing talent. So what does he look for in a prospective player? “A competitive fire in the student-athlete [and] intangibles that can’t be taught such as hustle, heart, and work ethic,” he says.

“Obviously the student-athlete must be skilled as well”

Recruiting has evolved, notes DiGiorgio. “High school basketball is just a part of the process. There is club ball — OBA and AAU — as well as provincial teams and regional teams.”

Recruiting has evolved, notes DiGiorgio. “High school basketball is just a part of the process. There is club ball — OBA and AAU — as well as provincial teams and regional teams.”

Initial recruiting occurs in the final two years of high school. Athletes often apply to U of T through the OUAC website like any other student, at which point coaches invite them to visit campus to see a game or practice and meet the current players on the team.

Open tryouts are held directly after training camp, and one or two student-athletes are recruited onto the team.

Students lacking competitive experience are encouraged to play pickup basketball or join a club team. “The thing with basketball is that it is a very accessible sport,” says DiGiorgio, “all you need is a ball and a rim and you can work on your game.”

Nicholas Irvine is a first-year life sciences student. Prior to joining the Blues, Irvine played on British Columbia’s provincial team as well as for several club teams.

“A lot of your time off the court has to be spent in the library studying and finishing assignments,” forward Irvine advises potential recruits.

Mile Pajovic, a first-year Rotman Commerce student, has played for OBA and AAU club teams since the fifth grade, as well as his high school team. Pajovic believes basketball success all boils down to one core factor: “Work hard.”

Teammate Alejandro Prescott, a first-year Spanish and Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations double-major, has played for both his high school team and Ottawa Next Level. Prescott echoed Irvine’s message. “Put [your] schoolwork first. The most important thing for a varsity athlete is to maintain his or her eligibility.”