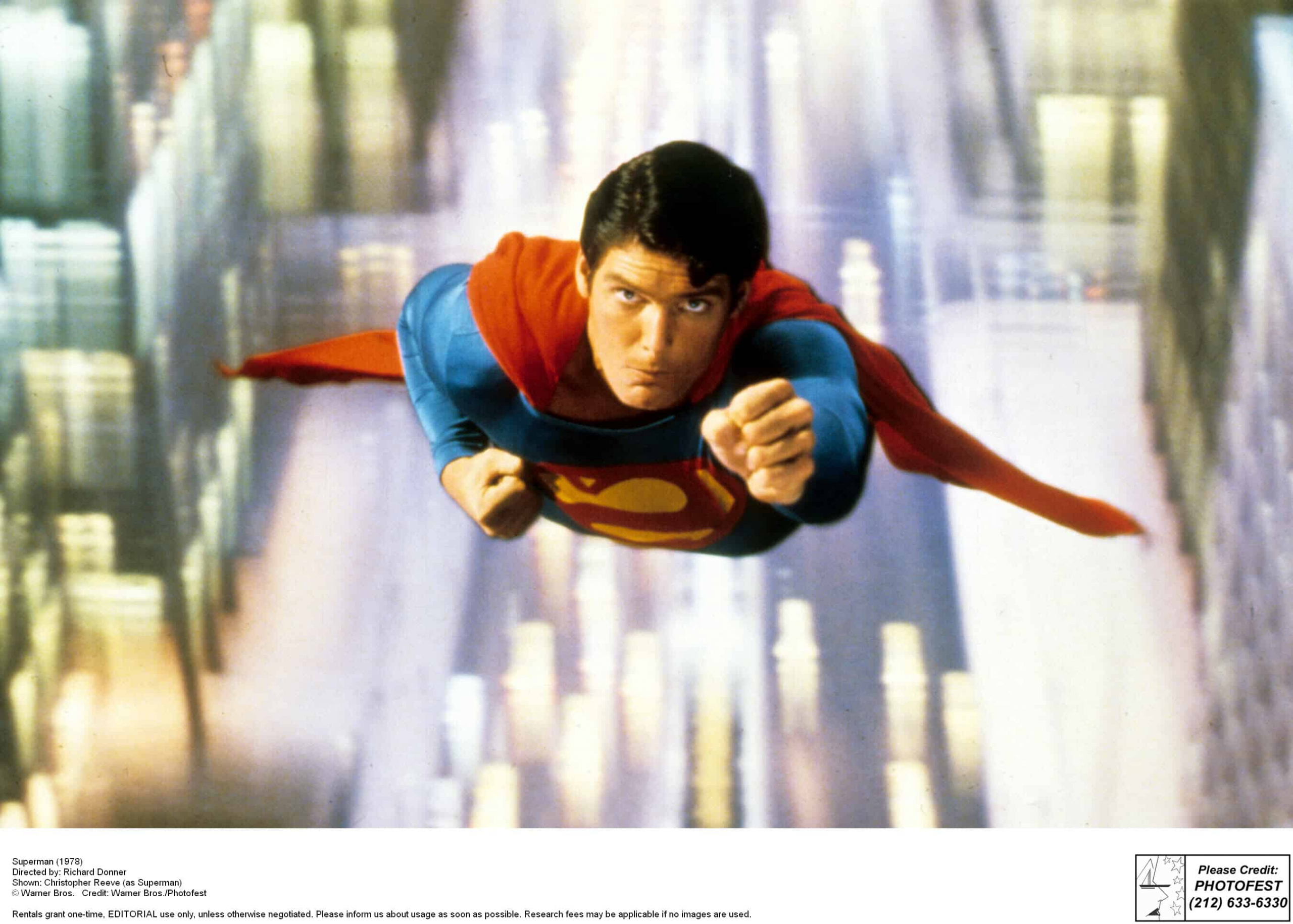

The TIFF Bell Lightbox is currently hosting a matinée series of old-school, kid-friendly comic book adaptations. It’s March Break this week, and the Comic Book Heroes series is designed to keep youngsters off the streets and out of trouble while the rules and obligations of school temporarily disappear. While Comic Book Heroes is marketed to kids and families, the opportunity to see Christopher Reeve, among others, flying through the air on the big screen is reason enough for bored university students to take a break from their textbooks and stop by the Lightbox.

Most of the films are pre-Y2K, including Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Superman, and Dick Tracy. The series highlights a vision of comic book heroes that has perhaps been forgotten by recent audiences; we‘ve come to expect movies like Watchmen, in which the superheroes are bums and losers, or the newest Batman film, which features scene after scene of the Dark Knight getting his ass-kicked. The tiff series focuses on earlier, less gritty depictions of super heroes — the goofy spandex-clad heroes full of bravery and righteousness, along with the square-jawed villains and their terrible one-liners. One of Dick Tracy’s nemeses threatens to “take his fingers and turn ’em into pretzels!”

Jesse Wente, series curator and Head of Film Programmes at the TIFF Bell Lightbox, explains why he thinks kids are fascinated by superheroes. “As a kid, you’re trying to work out your individual identity, and I think superhero movies often express those sorts of ideas or the emotions surrounding that. Superheroes, yeah, they have super powers, but that often complicates their lives. They can’t be part of the same social group as they might want to be, and all those issues are things kids deal with in school or the playground on a daily basis.”

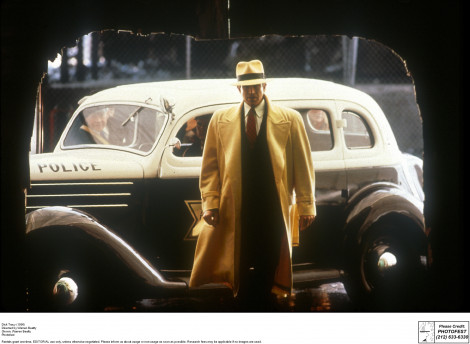

Dick Tracy (1980). PHOTO COURTESY PHOTOFEST

It seems that the same could be said about university students. Issues concerning one’s “individual identity” perhaps especially apply to those in fourth year, who are shuddering at the question of “what’s next?” But Wente offers other reasons as to why university students might be interested in checking out the series. “Some of the movies provide a certain nostalgia or connection to superhero cinema past like Superman and those sorts of films,” he says. “For university students, it’s an opportunity to see films you may not have seen on the big screen before.”

Nostalgia is both a pro and a con. The films’ effects often seem outdated, looking like kindergarten arts and craft projects. Perhaps even more disappointingly, Batman: Mask of the Phantasm — the animated film that closely resembles the super-gritty ’90s television series — at times fails to live up to favourable memories of the show. At one point, an agitated Batman whines to his butler Alfred: “Don’t you know anything about me?” Teen-angst Batman is perhaps better left forgotten.

Barring a few quirks, however, Mask of the Phantasm is still an edgy cartoon. As Wente admits, “It’s the most intense of the films we’re showing… For kids, it might be an okay entry point for Batman. Batman is always intense. They are really dark stories, those stories. It’s hard to include them in a series that is trying to be kid-friendly.”

On the opposite side of the spectrum, the series is screening movies like The Powerpuff Girls, which features three super-powered girls that are chemically concocted with sugar, spice, and everything but a prescription to Ritalin. Within this genre of hyperactive, sugar-rush cartoons, the Lightbox also includes Astro Boy and Speed Racer.

A notable trend throughout live-action films in the series is the tension between real-life actors and animation. Both Dick Tracy and The Mask include cartoony makeup and attempts to render the live action into a more comic book aesthetic. Wente says that a question at the centre of the series is: “How do you adapt a comic to the screen?”

“It’s funny,” says Wente, “Because nowadays so much popular cinema is cartoons interacting with human beings. Or human beings within giant cartoon landscapes that don’t actually exist. We’ve come to a point where that’s more of a norm in popular filmmaking than it is the exception, as we see in some of these early movies [like Dick Tracy].”

Wente points out that a comic book adaptation faces particular issues different from other adaptations. “Unlike, let’s say, a novel adaptation that doesn’t necessarily have a visual design already associated to it, comic books have a very specific visual design to them. Certainly, they change with different artists or what not, but Spiderman has a very distinct look to it. How do you create that on the screen? Or how do you create Superman on the screen? Make it into a world that you could buy into. I think it’s one of the difficulties that kept comics marginalized for so long.”

Wente says the inspiration for the series came from a desire to watch the original 1978 Superman film on the big screen. Along with Superman II, Wente says, “It would be hard for me to imagine doing the series without being able to show those.” Superman may be one of the corniest, cheesiest films in the series, but it also has a lot of heart. The first half of the film focuses on the origins of Superman, and then shifts gears to portray Superman catching bank robbers, saving journalists dangling from helicopters, and escorting a little girl’s kitten from a tree. It’s a bird, it’s a plane — no, it’s just a really great guy!

So while TIFF’s Comic Book Heroes is definitely kid-friendly, the series offers a great opportunity to reminisce about an earlier time, when villains were more comical than evil and superheroes really were super.