After decades of being pushed out by digital technology, analogue film has been rescued by a culture of reuse that favours recycling and repurposing traditional machinery. With artistic intrigue overpowering technological advancement, there has recently been continuous development in the field of experimental film. In particular, the field has moved toward appreciating the physical capabilities of the medium, which has opened a door to expressing the physicality of the natural world through film development.

Conscious creation: What is used to develop film?

Film development can never be fully eco-friendly, but there are alternatives to traditional methods that can mitigate environmental risk by reducing the consumption of harmful chemicals in favour of natural elements.

Traditionally, film is composed of silver halide, and once it’s exposed to light via a camera — when you take a picture — the silver is activated, or ionized. To achieve a negative — an inverted photo that can later be used to create a finished image — a developing agent turns the activated silver particles black, a process called oxidation that takes place in the dark. A ‘fixer’ is then applied to remove the unexposed silver halide from the negative, which would otherwise darken the finished image over time due to its light sensitivity.

Film developing agents are often primarily composed of phenols, which are organic compounds commonly found in plants, wine, and coffee. Film developers made from wine and coffee produce the same effect as the traditional chemical approaches to black and white film — a technique known as eco-hand-processing.

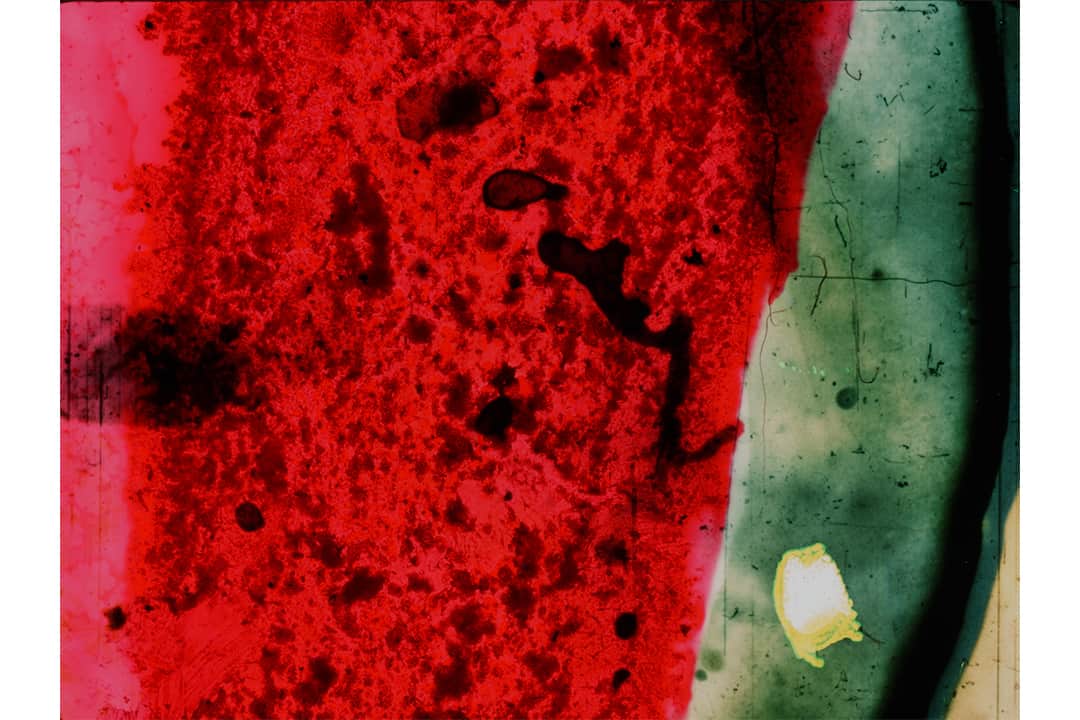

Film developers can achieve a more prominent grain and greater contrast when they have chemically basic bases. Developers from coffee, grass, potatoes, and wine are all different types of bases that enhance this creative process, technically defined as caffenol, grassenol, kartoffel, and wineol, respectively.

Their nuance is obvious in their finished product, and artists can rest with the knowledge that they can be disposed of easily down the drain, compared to their chemical counterparts that cannot be easily recycled because of their high toxicity.

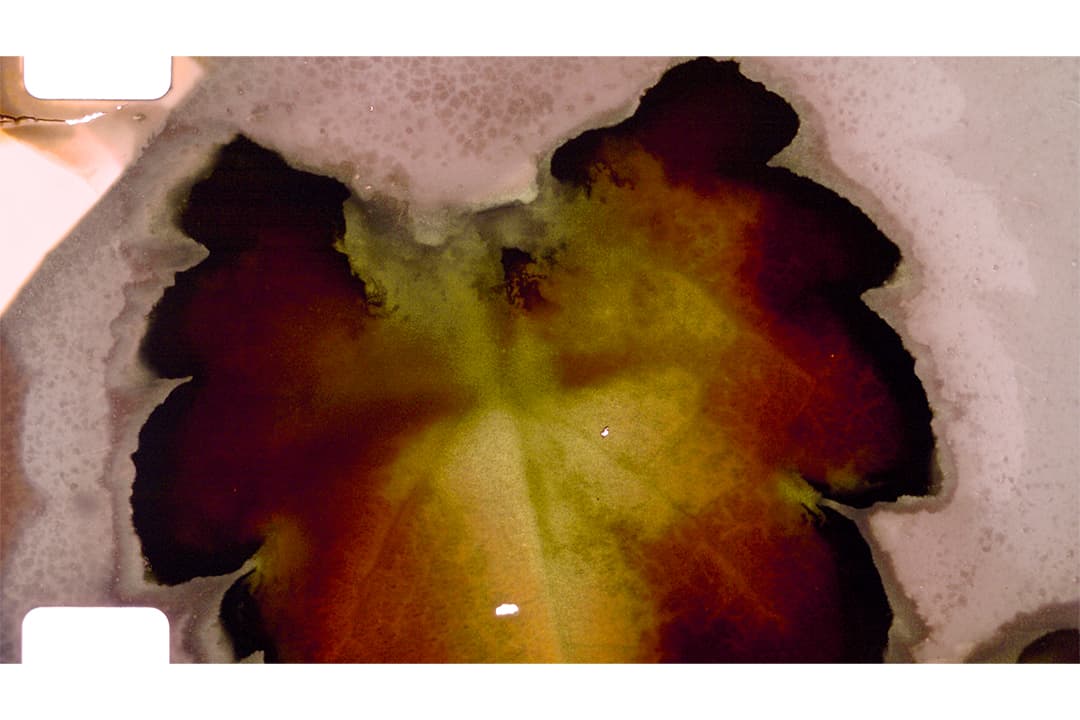

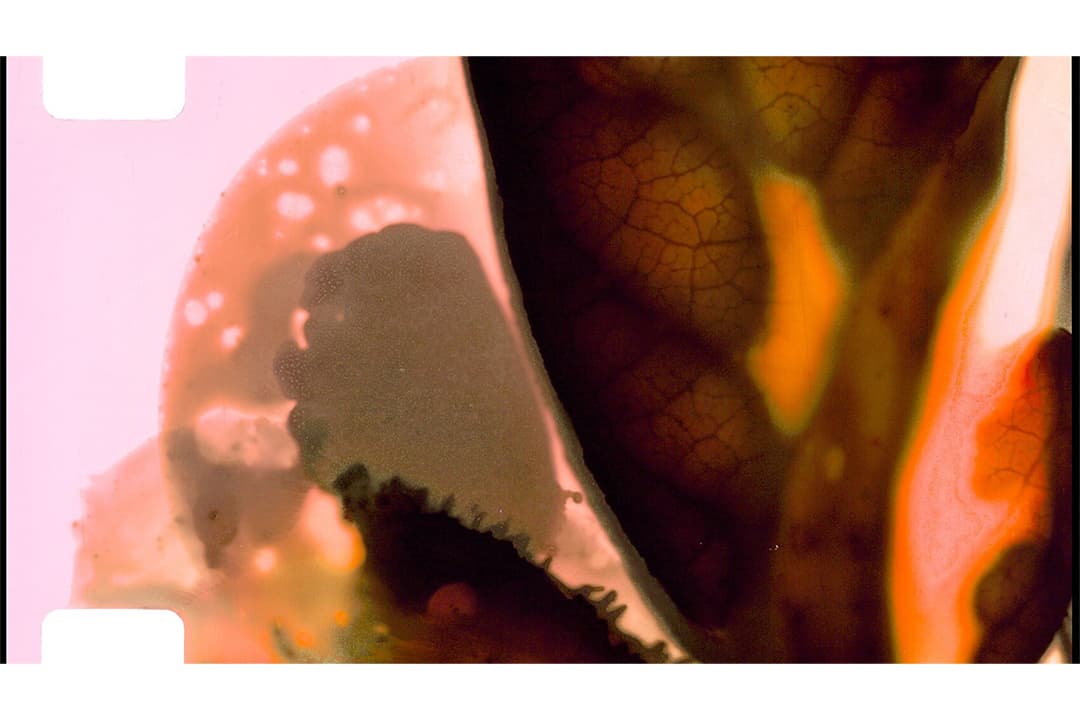

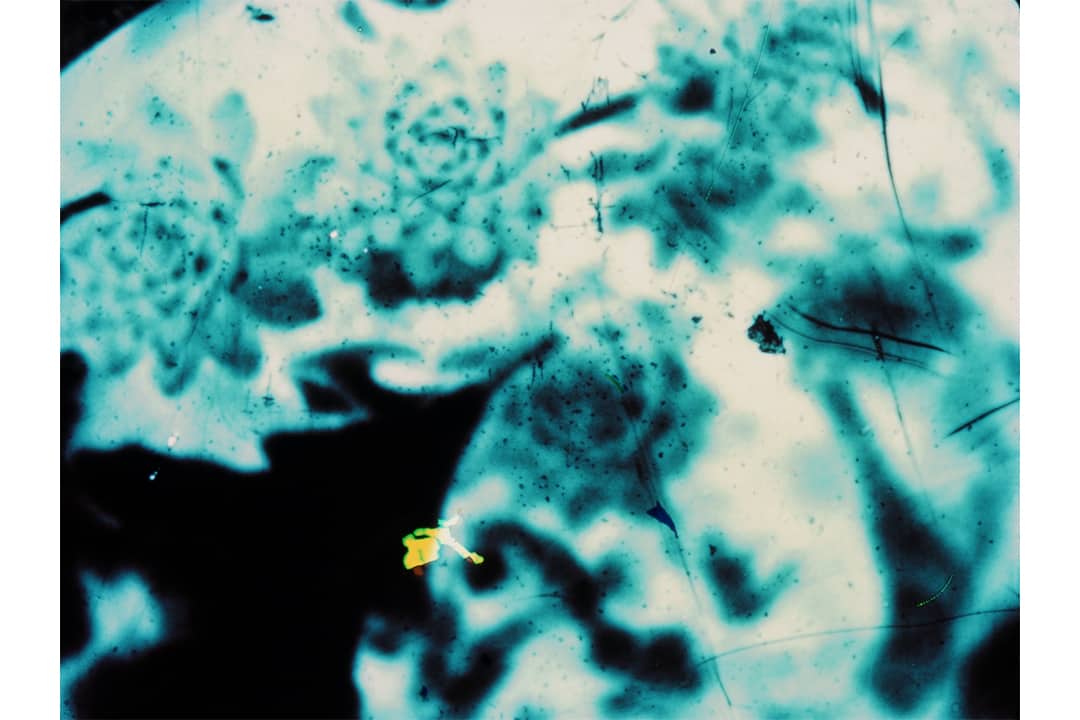

Phytograms are another means photographers can use the natural world in film development. By relying on the internal chemistry of plants to create chemical traces on film, the use of phytograms avoids toxic procedures. In this method, however, no camera is used — it’s all about sunlight. Phytogram photographers immerse plant matter, including leaves, flowers, or grass, in a developer made of vitamin C powder and sodium carbonate, then place them on the gelatin on the film. To reveal the physical structure of the plants — such as the veins in the leaves or the division of flower petals — the film must be left in sunlight for the gelatin to swell according to the individual internal chemistry of the plants.

Both phytograms and eco hand-processing use readily-available, low-cost, and low-toxicity items to produce film, making the practice more friendly to the planet and accessible to those who wish to experiment in this niche field of art.

Community connection

In her book Experimental Film and Photochemical Practices, Kim Knowles describes the phenomenon of the radicant — a plant whose roots extend outward with purpose, whether to climb, to creep, or to crawl, ever-searching for direction — as a symbol of the precarious identity and adaptability of the film community.

At the centre of photochemical film culture sits education and community, composed of those who seek to share knowledge that embraces unconventional approaches to film that align equally with political engagement and ecological awareness. Artist-run film labs and independent filmmakers have kept analogue film alive outside of commercial film labs, spreading a model of skill-sharing rather than profit — an approach that encourages artists to be conscious of how their work impacts the environment and society.

Doing the ‘wrong’ thing has historically unearthed an abundance of possibility for innovation in experimental film. Innovations, such as eco hand-processing and phytograms, have emerged from creative rule breaking. Toronto itself is a hub of learning and exploration for film. The Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto (LIFT) is a local member-driven non-profit organization that offers residencies, workshops including those on eco hand-processing, rental equipment, and affordable access to other resources with the mission of supporting independent filmmakers and artists.

Francisca Duran — an experimental Chilean-Canadian filmmaker based in Kensington Market who evokes raw visuals in her work with the phytogram technique — and Philip Hoffman — a contemporary Canadian filmmaker and artistic director of the Independent Imaging Retreat (or Film Farm), which leads programs in the particularities of hand-processing analogue film — are among Toronto’s key figures in experimental film.

They, and many other local artists, are known to grace postsecondary school lecture halls to spread their knowledge. Through the work of artists like them, amid the overwhelming technology of the digital age and the ever-changing state of the planet, analogue film persists.

No comments to display.