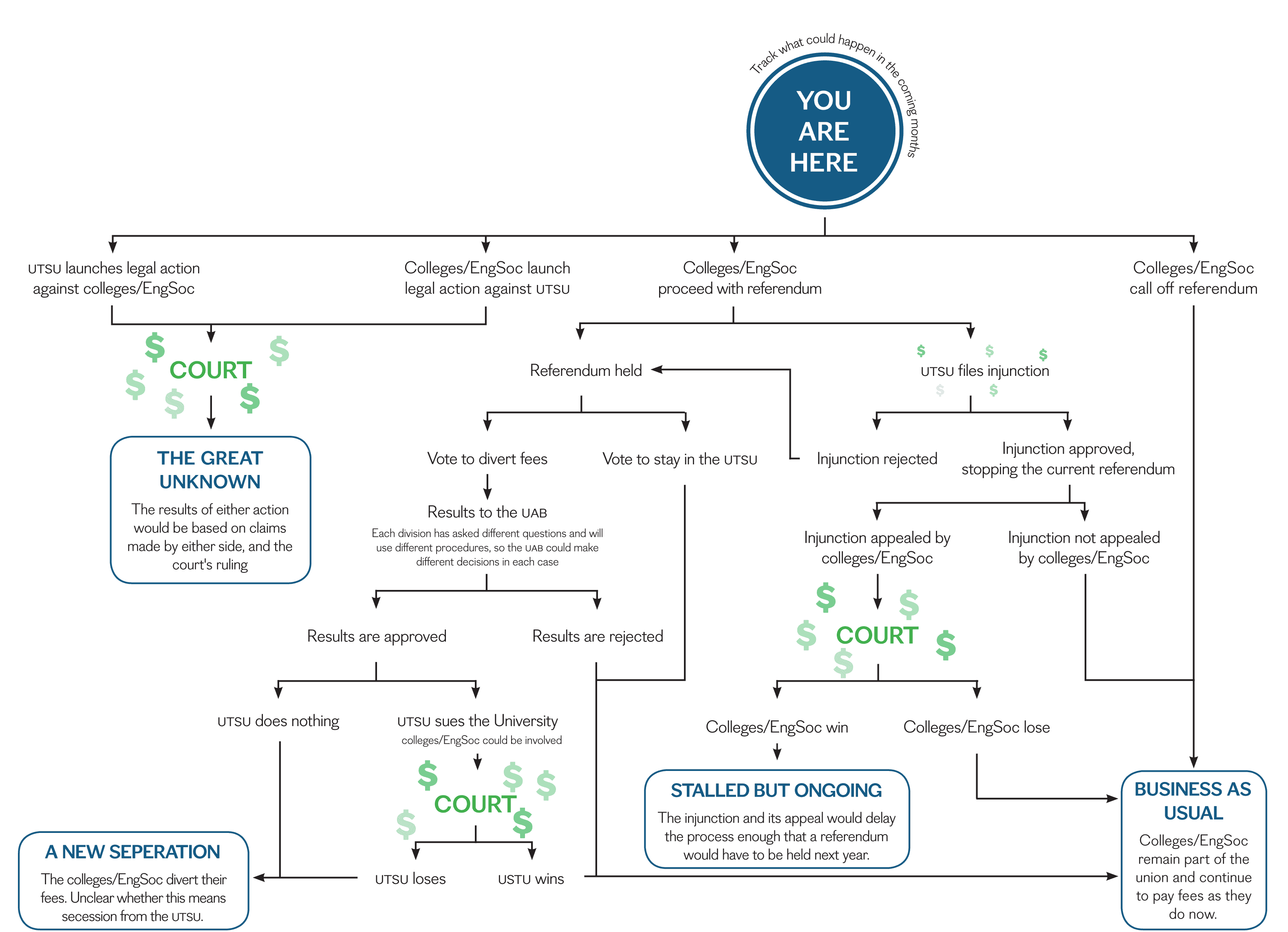

In the last few weeks, the pages of this newspaper have been filled with talk of ‘defederation,’ a colloquial way of referring to the attempts by the Engineering Society (EngSoc), St. Michael’s College Students’ Union (SMCSU), the Trinity College Meeting (TCM) and Victoria University Students’ Administrative Council (VUSAC) to divert their students’ fees from the UTSU to their respective councils. As you can see above, there are a number of ways in which those attempts could lead to court battles.

It is difficult to predict what form a possible legal action could take. If the referenda proceed, and their results are accepted by the university, it is unclear what legal precedents would apply if the case goes to court. The case being cited by both sides, APUS vs. UTMSU and EPUS (Erindale Part-Time Undergraduate Students’ Association), does not seem to be a clear precedent. According to those involved in the case, the principle that the judge seemingly upheld is that one organization cannot interfere with the internal workings — membership, for example — of another organization.

As the UTSU has pointed out repeatedly, under its bylaws, every full-time undergraduate at the U of T is individually a member of the union. The UTSU seems to implicitly recognize the faculty and college structure in the makeup of its Board of Directors, but there is no formal recognition in the bylaws. The APUS case seems to be based on a federation structure, so it is not immediately obvious that it applies to the present case.

With both sides displaying confidence in their legal position, any court case will likely be prolonged and expensive. Attempts by various student councils and unions to defederate from the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS) have resulted in huge legal fees — over $407,000 in the case of the University of Guelph Central Student Union. There are significant differences between the CFS defederation cases and the present situation. The CFS is a federated body; the UTSU is not. The CFS also has a record of litigation, with long legal battles employed to wear down the unions attempting to defederate and run up huge legal costs; the UTSU has no such record. But the ‘war chests’ being assembled by some of the divisions clearly suggest they fear a legal contest.

In November, the EngSoc hired Heenan Blaikie LLP (the firm that represented Guelph in the above-mentioned CFS case) on a $10,000 retainer, and has a $67,000 legal fund in place. The tcm has retained Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP with a budget of at least $100,000. Although the UTSU does not list legal costs explicitly in its year-end financial statements, it retains legal counsel and has the money to sustain a long legal battle.

But where does all of that money come from? It comes from your student fees. The college and faculty councils, and the UTSU, receive a portion of the student fees you pay every year. It is possible that in the battle to divert or retain the UTSU portion of your fees, those same fees will be spent on litigation. These fees would be better spent serving members, rather than on legal infighting among students.

There could also be broader consequences to a legal fight. Any fee diversion would have to be approved by U of T’s University Affairs Board (UAB), a committee of Governing Council. If faced with referendum results calling for fee diversion, it is unclear what the uab will do. But if the UAB does approve fee diversion, it is possible that the UTSU could take legal action against the university itself. That action could call into question the university’s right to make decisions on student societies’ fee changes, upending the way incidental fees are organized and controlled at U of T. This means thats legal action could do more than cost you money — it could fundamentally alter how students and the administration interact.

The U of T faculty and colleges attempting to divert fees at U of T are each at different stages of the process. VUSAC, TCM, and EngSoc have issued reports detailing how fee diversion would work; SMCSU has yet to publish a report. Some students have criticized these reports as inconclusive or under-researched, an understandable critique considering their short time frame. Discontent has been brewing for some time, but fee diversion is a fairly recent phenomenon. Its current iteration has only been in existence since last month’s UTSU Special General Meeting. Six weeks is not enough time to educate affected students about the potential financial and structural implications of fee diversion. Considering that it also takes time to plan, publicize, and run the referenda, it is questionable whether there has been enough time to run an effective campaign that benefits students.

The UTSU, for its part, has failed to head off the attempts at fee diversion. The union provided a response to the TCM report, and has been in correspondence with the various units planning referenda, but it has not taken sufficient public action to inform students about the consequences of fee diversion. Nor has it acknowledged that some of the student grievances driving the movement may be legitimate. Successful fee diversion would have enormous financial consequences for the union, and would seriously undermine the UTSU’s claims to speak for all U of T students. President-elect Munib Sajjad’s decision not to answer questions about litigation may have been legally prudent, but he and his team have done little to inform students about the implications of a court battle and to bridge the gap in campus politics. Meanwhile, the recent electoral withdrawal of executive candidate Sana Ali and her criticism of the Renew slate suggest that there is a divide even among the union’s supporters.

Both sides justify their actions by claiming they represent the will of students on campus, but a large number of students, perhaps even a majority, are unaware of most campus politics, let alone the recent battles between the union and its divisional opponents. These students are also unaware that the ill-considered decisions both sides are making could lead to a legal battle, the result of which is uncertain except for an unnecessary financial burden on students.

Both sides have repeatedly offered to settle their differences through consultation and compromise, yet no solution has been achieved; each side blames the other for this dispute. The best and least expensive way of obtaining a solution is through outside mediation — an objective, professional third party who could resolve the disputes between the union and their divisional opponents, and ensure that much-needed structural reforms are made within the UTSU. This method of resolution could usher in a new era of mature, conscionable governance. The mediator would basically reboot union and student relations, and lessen the probability of a legal battle.

Student leaders on both sides of the fee diversion battle must back up their rhetoric with a willingness to make substantive concessions in the presence of a third-party mediator. This is the best way to avoid a protracted, expensive, and risky legal battle, which is the worst possible outcome for students.