You may not be aware of it, but there’s a new music scene on the rise in Toronto, one that’s been taking shape since the late 2000s. Second- and third-generation Punjabi youth in Canada and the gta have been paving the way for an Indian rap scene without any real precedent. If you bring up the topic of Punjabi rappers to the average Torontonian, they’ll likely respond with quizzical expressions, unaware that desis even dabble in the art form. You can roughly trace the movement back to the summer of 2008, when the now defunct partially-Indian Brooklyn rap group Das Racist rose to viral fame with “Combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell.” Around the same time in Toronto, albeit on a smaller scale, R&B vocalist Selena Dhillon, and her close colleague, MC/spoken word artist Humble the Poet, began independently releasing their own self-recorded tracks through social media channels. These little sprinklings of talent slowly gained steam, creating a network of Punjabi musicians that frequently collaborate with one another on projects addressing the social and cultural issues closest to them. They hail from all across Canada, and credit Toronto’s diversity for cultivating their movement. These artists are diverse, but to quote Dhillon, they’re united by a shared “work ethic, hunger, and a passion to get their music out there.”

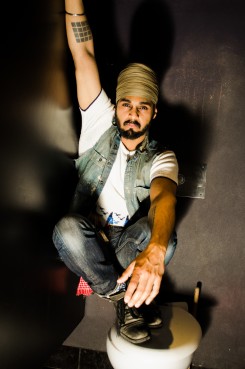

A relatively new member of the scene, but already vital to its longevity, is Kanwar Anit Singh Saini, a producer/DJ who makes beats under the moniker Sikh Knowledge. Working and living in Toronto for the past six months, Saini grew up and made a name for himself on the streets of Montréal. He based his decision to test out a new city on several factors: “Montréal was cool but I’d have to say, it was really electro, soul, and funk oriented. Toronto has that red, gold, and green West Indies vibe to it and that’s totally me. That’s a big part of my influence, so I jar well with a lot of what’s going on over here musically.” Amrit Tung, a colleague of Dhillon and Saini, is better known as the rapper Noyz and for his status as a member of the new rap collective, Zoo Babies. Tung is a well-established local who values his suburban roots: “I grew up in Mississauga and Brampton. Both places are very multicultural and home to a lot of newcomers and immigrant families, so I had friends from many different backgrounds. It taught me to be accepting of everyone regardless of what they look like or where they come from.” Dhillon also grew up in Brampton, known for having one of the largest South Asian populations in North America. “Brampton has a lot of South Asians, but it didn’t hinder me in any way, it definitely opened gateways to get involved and familiarize myself with certain groups. For example, the rapper B Magic didn’t live too far from me, and he’s actually really good friends with my brother, so I’ve known him much longer as a friend than as a musical collaborator. It’s a huge community, and I’ve definitely benefited from that.”

The Class Question

All three artists grew up conscious of the stereotype that South Asian parents discourage their children from pursuing a career in the arts. Strike up a conversation with any South Asian kid in the gta, and you’re bound to hear a few stories detailing an early love for the arts that either faded because their parents exuded disinterest, or insisted that such activities remain in the realm of casual hobbies. Revisiting the experiences of these three musicians, it’s clear that there’s no set pattern to help measure how any South Asian family might respond to one’s legitimate pursuit of a musical career. For instance, Dhillon happily rehashed details of her history with music. Her parents have been extremely supportive ever since she belted out Roberta Flack’s “Killing Me Softly with His Song” at the age of four. Dhillon’s father didn’t take a conventional career route growing up — he played professional soccer — and so, with a good grasp on the courage it takes to follow your dreams, he encouraged Dhillon to do the same.

Saini and Tung on the other hand, revealed that their families initially viewed the music industry as a risky endeavour. However, both of them kept at it until their parents realized how happy music made them. The bonus of bragging rights that came with local exposure also worked in their favour. Tung recalls that his parents were unable to comprehend his place in music until they saw him in his true element on stage: “After that, they were supportive and encouraged me to pursue whatever opportunities I could, but I still don’t think they see art as a viable career. I’ve been doing music while still going to university and fulfilling all my responsibilities at school, which probably makes my involvement in music easier for them to tolerate. I haven’t been in a situation where music is the only thing I’m doing in life, so I don’t know if they would support me to the same extent if that was the case.”

Saini shares a more humourous perspective on the road to acceptance in a traditional South Asian household, offering a critique of South Asian communities that instantly go on the offensive when they are met with the unfamiliar: “I feel like South Asian parents are often ‘attention-whores,’ so if they can get attention from the ‘community’ about something in a positive way, they won’t question it. In my case, I dropped out of engineering for music. But the irony is that our heritage and upbringing as people with a Sikh heritage and of Punjabi background is to inherently say ‘fuck you’ to whatever stands in our way.

“I said ‘fuck you’ to everything and I did it. Of course they were scared, and there was a lot of static from close family and friends for what I did, but I did it anyway. As soon as they started getting peripheral attention from what I was doing, for whatever reason, it was suddenly okay for them, which is a double standard. At the same time, I know they just want me to be happy, and they saw me so much happier in that milieu as opposed to whatever path I was previously following, so that was good for them as well.”

More than Bhangra

All three artists understandably cautious about paying allegiance to any one community, especially since their influences are not limited to Punjabi forms of music. Dhillon admits she didn’t really listen to Punjabi artists or bhangra growing up, instead spending her days surrounded by soul, R&B, and jazz. Saini, however, grew up heavily involved in his community, going to a gurdwara (Sikh temple) with his parents. As a kid at his local temple, Saini took part in kirtans. Kirtans involve chanting religious hymns with accompanying instruments such as harmoniums and tablas. But there was a heavy hand behind his involvement, which over time made the practice distasteful to him: “There were keeners that were way more into it and turned me off from the whole competitive kirtan vibe. At one point I remember as kids, it was a big deal who knew the most hymns and one kid knew 100 hymns, but 70 of them were in the same melody. It was just very ugly to me. Although I loved it, l left it alone.”

Tung also didn’t grow up with a strong awareness of mainstream Punjabi artists, apart from the few playback singers that dominated the Bollywood film industry. Instead, he relied on his older cousins for guidance in the world of Western pop and hip hop. “I would always go through their CD’s and cassettes when I visited them and borrowed the newest album they got, or whatever cover artwork caught my eye. I started writing because I loved the music and wanted to try my own hand at it.” Similarly, Saini credits older family members for exposing him to hip hop: “I have siblings that are much older than I am, so growing up I was always bombarded with mixtapes and new hip hop and reggae as a kid. I went to Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation tour in grade three. My sisters took me to that, so I was always very lucky that way. And so it was quite natural for me to think about these things all the time. I had mixtapes in my pocket regularly as a kid and I was beatboxing on my way to school. It’s just the way it was.”

The most striking fact about these musicians is that they are all self-taught. Beyond some important early influences, inspiration wasn’t necessarily forthcoming from close family and friends, but they’ve managed to emerge fully-formed and independent. This quality may account for their hesitance to stick to a single genre of music, or make music solely aimed at the Indian diaspora. Dhillon reiterates not wanting to box herself in a particular culture or religion: “My music does have a political aspect to it, but it carries through with the other work I do. I am currently doing my masters in International Affairs and I spent a couple months in South Africa with a grassroots organization last year, so again, I’m a voice for those that are not privileged. I have been speaking to the South Asian community with more recent songs like ‘Bang Bang,’ but I hope to cater to more groups, to break out of that single mold.”

Saini also insists that his music has a universal appeal: “It’s really meant for anyone who can get down to it. It’s nice that my fanbase is pan-cultural. There is a South Asian appeal to it, but when I make something I try to make sure you can nod your head to it regardless. Of course I have my stuff that I do on the side that is heavily Punjabi-influenced. But other than that, my roots, my foundations, are old-school hip hop and old-school reggae.” Tung also cites old school, confessional-style hip hop as a major influence in his writing, especially east coast acts like Wu-Tang, Nas, The Fugees, and The Roots. These Punjabi musicians grew up listening to their musical heroes, evolving in a sort of vacuum in which they gradually learned and perfected their craft.

Community helps – and hurts

Being labelled a Punjabi artist creates mixed feelings for this sampling of the desi movement. Association with a genre can feel limiting, but then again there is constant demand for their brand of music. The Punjabi community is small enough that word will spread quickly, and these artists can be assured of a dedicated audience for their work. Tung’s latest project, Zoo Babies, made up of himself, plus members Villa, Young Fateh, B Magic, and Babbu, is a prime example of the countless opportunities available in the scene: “Zoo Babies initially came together when a mutual friend to us all asked us to make a song for his birthday, ‘Supreme Duffle Bag.’ A lot of the lyrics contain references about him and inside jokes that only our friends would understand. The song was never meant to be taken seriously, but when we put it out, people seemed to really like the track and our group dynamic. The song generated over 250,000 views on YouTube, so we decided to put more effort towards making music as a collective and just have fun with it.” Tung claims this network has been advantageous in the sense that he’s become friends with incredibly talented individuals, their shared Punjabi heritage aside. Dhillon likewise points to the fact that the demand for their music is a huge motivation for her to keep going.

The community has provided her with many opportunities for collaboration: “I haven’t put anything out in almost a year, which drives me a little crazy. I’ve been working on my latest project over the last year. There is definitely a hunger for it, a lot of people want the music. Even if I’m not putting my stuff out there, I can still feature on other tracks. Last year, I only put out a couple of tracks on my own, but I had the opportunity to feature on Degrees of Freedom, Tung’s album, which in my opinion is a masterpiece.”

Acquiring an audience overseas is also easier when one is tagged along with this budding movement. Dhillon and Saini are happy to share that the response from the South Asian communities in the UK, Australia, and the US has been very promising, and fans far from Toronto are really paying attention to their development. Tung agrees, stating, “We often connect with what is most familiar to us, which is why I feel we’ve been able to generate so much support from the South Asian diaspora.”

Although support has been monumental, the community label is a double-edged sword, and clear disadvantages arise when assumptions swoop in about these musicians being the voice for all South Asians. As an openly queer Sikh man, Saini has come up against members of the Sikh community that resent the presence of ‘Sikh’ in his stage name. Saini used the metaphor of a mob to convey the negative effects that come with cutting off from the possibility of multiple identities: “It works to my disadvantage because you’re constantly trying to convince the mob of who you are. If the mob doesn’t agree with you, you might feel their wrath. So the trick is not to make music for any one group of people, but just make music. So you’ll notice on my fan page, I’m getting more and more non-desi fans, which is great. But I’m not trying to please the mob at all. Sometimes people who see the page Sikh Knowledge ask, ‘what is this page about?’ ‘What are these pictures about?’ ‘I want to know about Sikhism,’ etc. Just read up on me, I’m an artist, I’m not here to teach you about faith and heritage.” Tung agrees that non-desi listeners tend to be more skeptical when approaching their music. “They might expect us to sound a certain way, or assume that we only talk about things Punjabis will relate to… Any label we put on something can limit its potential reach. That just means we have to work harder to break people’s perceptions and misconceptions about who we are and the music we make.”

The Toronto Advantage

All three recognize that Toronto’s geographical location and diverse makeup have played a huge role in their success, allowing for the seeds to be sown for an exciting musical movement. Growing up as an Anglo-Quebecer of South Asian origin, Saini knows what it feels like to be a visible minority. Despite being fluent in French, he still came up against rampant discrimination while living in Quebec: “French Canadians, Quebecers, I feel aren’t exposed to our background as Ontarians are. Ontarians rub more elbows with people who grow up saying ‘My neighbour growing up was Punjabi,’ or ‘We went to their wedding,’ etc. You’ll get more of that here than you will in Quebec. In Quebec people are still kind of, ‘Who are Punjabi people? Who are Sikh people? Why are people wearing a turban?’ In Quebec, the generic term for an Indian is Hindu or Indou. It’s just not an exposed culture.”

Dhillon points to long-held friendships as another characteristic of Toronto’s standout Punjabi scene. “A lot of these relationships were established before we got into music. With some relationships, we reconnected when one of us knew another person, and it has created this huge web.” Noyz brings it back to the simple fact that quality hip hop has long simmered in Toronto. “There is a huge Punjabi population here, but I think it comes down to the quality of the music. It’s straight up rap and R&B with no gimmicks. We may incorporate Indian instruments in some songs, and some of us might dabble in fusion music, but we don’t let that define our sound. The music is true to the hip hop culture and can stand on its own.”