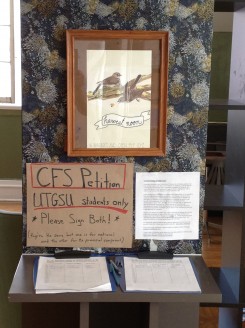

Despite the fanfare with which petitions to decertify from the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS) were launched across the country last week, as of Saturday night, the federation had yet to receive any petitions.

The CFS is an umbrella union to which U of T’s graduate, full-time, and part-time undergraduate unions — as well as 80 other student associations nationwide — belong. A press release sent to The Varsity claimed that students at 15 unions, including U of T’s Graduate Students’ Union (GSU), are petitioning to leave the CFS.

Students leading the various petitions at universities from British Columbia to Quebec had set themselves a target of Friday, September 13 to gather the signatures of 20 per cent of members from their respective unions. “We’re in the process of collecting the last few hundred signatures we need,” said Ashleigh Ingle, a former GSU executive and the person spearheading the movement, on Saturday. According to Ingle, the federation must receive petitions via registered mail by September 24 to allow for decertification votes to take place this academic year.

Brent Farrington, internal coordinator for the CFS, confirmed in an email to The Varsity on Saturday that no petitions had been received at the CFS national office in Ottawa. Under the federation’s bylaws, petitions must be received via registered mail, and the federation’s national executive must rule that a petition meets the federation’s bylaw requirements for a vote to occur.

The press release, distributed two weeks ago by the group of students organizing the movement to decertify, cited 15 separate student associations seeking to cut ties with the CFS. Associations with groups confirmed to be participating include the GSU, Laurentian’s undergraduate and graduate unions, Dawson College in Montreal, UBC Okanagan, Kwantlen Polytechnic University, and Capilano University.

The remaining groups could surface in the next few days, pending their petition submissions to the CFS. Many, however, have decided not to make their intention to launch petitions public for fear of proactive CFS interference, making it difficult to know how many campaigns to decertify are running.

Ingle said the response to the petition had been overwhelmingly positive. “Almost every single person we talk to signs the petition,” she said. According to Ingle, about 100 students are gathering signatures for the GSU petition.

Motives and plans

The decertification organizers have different motives and grievances, as well as different conceptions of their end goals. Ingle and Brenden Lehman, an executive at Laurentian University’s Graduate Students Association (GSA), claim a newly formed national student group is in the works, while other petitioners see the affair ending with decertification.

The level of collaboration and organization amongst petitioners also varies, leading some to believe that the “movement” may not be as widespread and effective as it was originally thought to be. Farrington commented that there seemed to be “divergence in messaging” among those leading the opposition to CFS.

Curtis Tse, former vice-president of the UBC Okanagan Student Union (UBCOSU), is leading the petition drive on his campus. He claimed that his previous involvement with the CFS via UBCOSU soured his view of the federation, particularly what he described as the “partisan nature” of the CFS supporting NDP and union groups. Tse believes that discussion with politicians, rather than spearheading lobbying efforts, would produce more effective results for students. He describes the decertification movement as “a grass roots initiative among many students,” with “little organization between [Okanagan] and other schools.”

Lehman is particularly concerned with the CFS’ financial priorities, claiming that the federation is unwilling to spend money acquired through services on advocacy: “The focus has to become more about providing those for-profit services than investing in effective lobbying and advocacy work,” he said.

Ryerson Student Union (RSU) president Melissa Palermo had a different perspective on the matter, expressing her union’s strong support for the CFS. She told The Varsity that the news of students attempting to decertify has been a surprise to many on her campus. She spoke highly of the CFS campaigns, saying they have a positive influence on the campus — citing the “No Means No” and “The Hikes Stop Here” campaigns, as well as other initiatives such as the International Student Identity Card, the improvement of campus food services, and the ethical bulk purchasing deal.

For Lehman and Ingle, a newly formed national student group is the ultimate aim, and Lehman says the founding congress is to be held in spring 2014. Lehman says the new organization will “present an alternative to students that will be member-driven; direct democracy-based; by students, for-students and not based on members’ money but their ideas.”

Ingle says that the positive response to the petition among graduate students at U of T indicates the depth of negative feeling towards the CFS among its members. While Ingle and her fellow petitioners are not quite sure how many signatures they require, since the exact membership of the GSU is unknown, she is confident that “we will be at least 1,000 above the number we require.”

“This is already the strongest mandate from students that we have ever had,” she said.

Confusion over role of student association executives

Confusion surrounds the role that an executive of a CFS-member union may play in a petition or decertification campaign. A “CFS-member union” refers to the organization or group that has the authority to vote on behalf of the members at a particular campus. Ingle, the 2012–2013 civics and environment commissioner of the GSU, cited comments from former CFS national chairperson (and former UTSU president) Adam Awad to The Charlatan newspaper at Carleton that suggested executives of member associations could not submit a petition for decertification.

Alex McGowan, a student spearheading the decertification petition at Kwantlen Polytechnic University in British Columbia, echoed Ingle’s claim. “The bylaws in the Canadian Federation of Students … don’t allow for student associations to directly take part in petitioning for a referendum [to decertify],” he said.

Farrington made a distinction between associations taking a stance on decertification and executives of those associations acting in their individual capacities. The CFS’ bylaws require that member unions support the implementation of the federation’s objectives and policies, and work ‘cooperatively’ with the federation’s staff and executive. These bylaws, Farrington suggests, do not allow for an association to take a pro-decertification stance or to organize a petition.

The executives of a union, however, acting as individual members of the union concerned, do have the right to circulate petitions, though Farrington suggested that would create an ‘image conflict.’ He cited the case of the Laurentian University GSA, which recently “passed a resolution saying that [an executive promoting a petition] should cease that work, if he’s going to continue to be an executive member at that union, because he is out of alignment with the policies set by the membership of the student association.”

Lehman, the Laurentian executive to whom Farrington was referring, refutes that claim. The statement, issued through the GSA’s Facebook page, states that the association does not advocate decertification, though it “is aware and understands” Lehman’s actions, but that the association itself was in no way connected to the petitioning. “There was no request to cease,” Lehman says.

The GSU and UBCOSU have chosen to remain neutral in their stance toward students petitioning for decertification on their respective campuses.