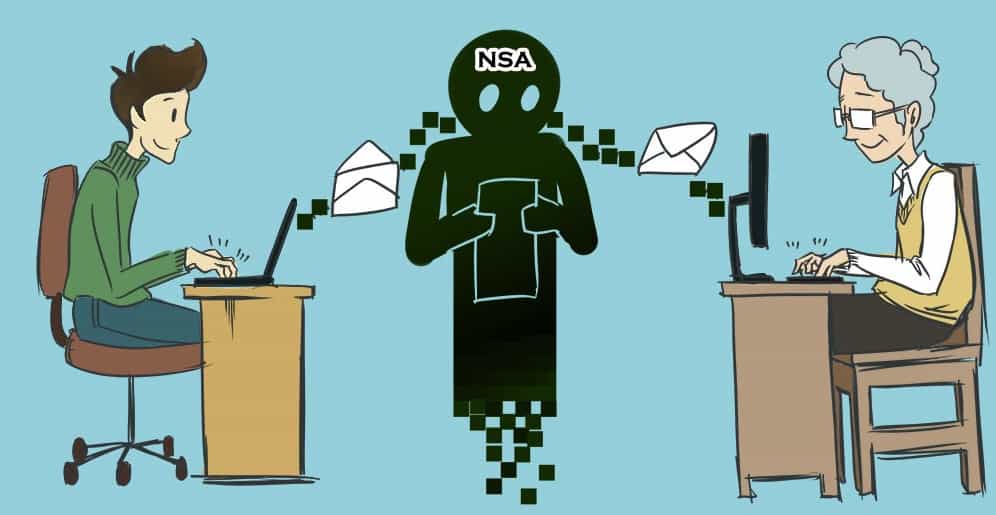

The University of Toronto has moved roughly a quarter of all emails from UTORmail to a globally based Microsoft server, raising concerns that email will now be monitored by the National Security Agency (NSA).

Since fall 2011, the university has moved over 135,000 students to a free Microsoft Outlook platform with servers located around the world, including in the United States. Over thanksgiving weekend, the system was upgraded to Office 365. The university describes the move as a user-friendly, cost-saving measure that was decided through an open and consultative process. This move has received little publicity from U of T’s Information Technology Services (ITS), who are responsible for implementing the switch. A series of town hall meetings and consultations by a small committee of students and staff from each campus were held prior to the switch.

The meetings, which occurred over a period of more than two years, aimed to address the protection of privacy and identify the e-communication needs of students. Concerns over data mining by the NSA, as brought to light by former intelligence contractor Edward Snowden, were investigated.

“Our agreement is with Microsoft Canada, but the services are provided by their world-wide cloud environment that includes US data centres,” said Robert Cook, U of T’s Chief Information Officer (CIO). Now that faculty and staff are facing a transfer to the same email platform as students, there is heightened anxiety over outsourcing to US-linked corporations. This is because Microsoft and the university cannot guarantee full privacy to their users.

James Turk, executive director of the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT), represents those against outsourcing. “All of your records and data come under American terrorist laws, so American cloud providers like Microsoft are obligated to turn over records in their servers to the NSA if requested, and the NSA doesn’t have to have a specific reason to do so. Microsoft is also required by law to keep customers in the dark about these requests,” said Turk.

He further noted the dangers within the Microsoft contract itself: “The agreement makes reference to various policies, all of which are very complicated and may infringe on our academic freedoms. Emailing an article as an attachment could become risky and threaten our intellectual property rights. The problem is that we just don’t know who is looking at our records.”

Andrew Clement, professor at U of T’s Faculty of Information, is also concerned about the cloud servers. “The university hasn’t done a good job of educating students on the dangers of outsourcing. What’s more, we know less about what’s going on in Canada in terms of surveillance, but we do know that the US has acted unconstitutionally and without appropriate oversight in the past,” he said.

Cook noted that there was plenty of consultation and communication over the past two years as to the transfer of student email, and asserted that there is demand from the faculty to use the same service. “The infrastructure underpinning [the faculty’s] current services is end-of-life and at risk of failure. We want to equip our community with contemporary communications services that will support our academic excellence,” he said.

One of the main motivations in switching to Microsoft is money. “Money saved by the university in providing commodity services is money that can be directed to the core university mission, including teaching and learning,” said Cook.

Due to the drop in government funding for universities, U of T is looking to save wherever possible. “Microsoft has a sophisticated system and it is free, so it is a creative way for the university to save money,” agreed Turk.

By working together, the university receives financial benefits, and Microsoft gets publicity by signing a contract with a trusted educational institution. “Other universities are now using this server, which builds a broader base of people invested in Microsoft’s technologies,” said Clement, “Microsoft can now perhaps get students to stick with its service after graduation, which makes them more money.”

The alternatives to Microsoft seem few and far between. According to Clement, universities are hesitant to invest in their own cloud servers, which would fundamentally prevent issues with encryption. “The University of British Columbia (UBC) is doing it, so that could be a possibility,” he said.

Students were given the option to not establish a Microsoft account, and instead have their email redirected to any service of their choice. However, most students decided to switch to Microsoft. “Fewer than one half of one percent of subscribers opted out of the Microsoft cloud and satisfaction is very high,” said Cook.

Munib Sajjad, president of the University of Toronto Student’s Union (UTSU), thought the compromise for modern technology was a poor shortcut: “I do believe the university was looking for ways to offload the burden of putting together a new email client… [U of T] could have done better to research email clients that could have greater protected the rights and freedoms of our students.”

Correction Thursday, 28 November 2013:

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the email system was upgraded to Office 365 last week. The upgrade took place over Thanksgiving weekend. A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that approximately 1/4 of students have been switched. Approximately 1/4 of all emails have been switched.