“We, the management of this organization that are trusted with stewarding this space… we offer an apology,” Brandon Rhéal Amyot — the then-chairperson of the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS) — told the student union representatives gathered in an Etobicoke hotel conference room in November for the CFS’ 2023 National General Meeting (NGM).

I had come to the CFS NGM as a reporter, having learned from documents left by my news editor forbearers that The Varsity used to attend and report on the NGM regularly. When I entered this meeting, I knew little about the CFS besides that people I talked with generally seemed to hate it and that almost every U of T student on campus belonged to it.

Over months of reporting, I learned that part of the reason the CFS remained a mystery was because of a shift away from the organization by the UTSU, a lack of coverage by news outlets — including my own — and a greater apathy around student politics.

Despite having worked at The Varsity for two-and-a-half years, I couldn’t even initially determine what exactly Amyot hoped to apologize for. I only learned later that they were apologizing for disorganization at the meeting and alleged microaggressions against Black and Indigenous students.

I believe myself to be a relatively well-informed member of the campus community: I follow and vote in student union elections, can rattle off enrolment numbers, and continually rant about U of T’s policies and governance decisions — much to my friends’ chagrin. However, over months of reporting, I learned that part of the reason the CFS remained a mystery was because of a shift away from the organization by the University of Toronto Students’ Union (UTSU), a lack of coverage by news outlets — including my own — and a greater apathy around student politics.

After leaving the NGM, I read reports, delved into The Varsity’s past coverage, and spoke to student union executives who sat in that hotel conference room. Some of those executives called for U of T students to engage more with the CFS. Others said that their unions should leave it entirely.

Regardless of how one believes students should engage with the CFS, one thing remained clear throughout my research: without oversight and attention from individuals and organizations, governance bodies such as the CFS that are meant to represent students — and continue to rake in our money — will remain in subpar condition, failing to address issues that matter to students.

A successful, vibrant student movement has the potential to impact the policies that shape students’ experiences during our years on campus. Currently, the CFS has little impact on most U of T students’ day-to-day lives. But the history I uncovered shows that inspired students have the tools to ensure that changes — and that change has always begun with a basic awareness of both national and local organizations.

What the F is the CFS?

In 1981, the Association of Student Councils (AOSC) and the National Union of Students (NUS) merged to form the CFS, joining the political advocacy spearheaded by the NUS with the services provided by the AOSC. The fledgling organization focused on cutbacks in postsecondary education funding and other issues that restricted students’ access to education, including sexual harassment, fees, and international crises.

The University of Toronto Graduate Students’ Union (UTGSU) and the U of T Student Administrative Council (SAC) — the precursor to the University of Toronto Students’ Union (UTSU) — both attended the founding meeting, with the UTGSU joining that year.

Other U of T unions gradually joined the club: the Scarborough Campus Students’ Union (SCSU), the Association of Part-time University Students (APUS), and the SAC ran a joint referendum to join the CFS in 2002. However, the university at first declined to collect the unions’ CFS fees, as it does for other unions as part of students’ ancillary fees, citing a “systematic advantage given to the ‘YES’ side” in the referendum to join the CFS.

U of T then reversed course and began collecting the APUS’ CFS fees in 2004 and the SCSU and UTSU’s CFS fees in 2005. The University of Mississauga Students’ Union (UTMSU) split fully from the UTSU in 2018 but remained part of the CFS — essentially grandfathered into the federation.

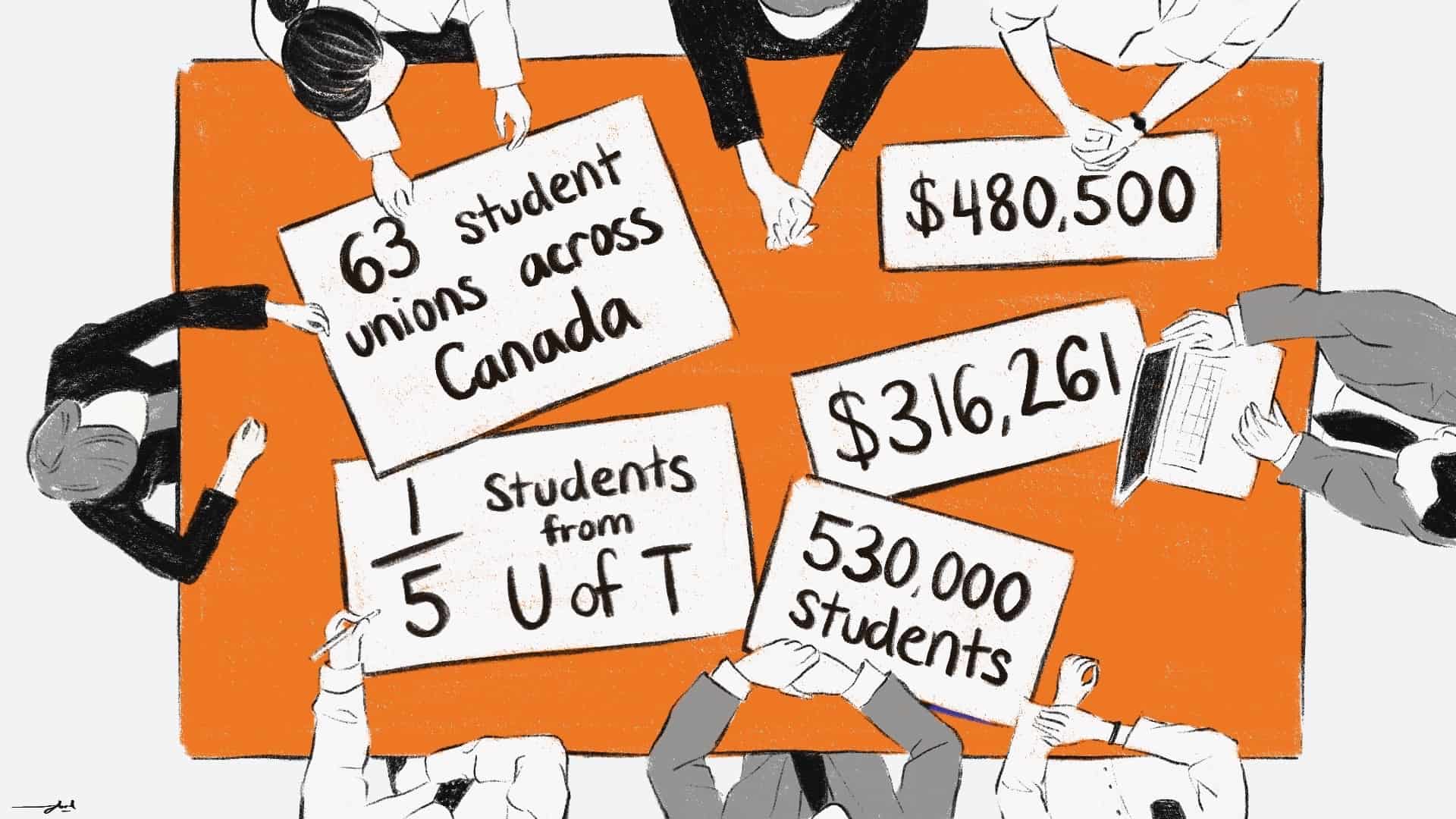

Today, the CFS represents 530,000 students from 63 student unions across Canada. It provides various services and continues its quest for free and accessible postsecondary education. Almost a fifth of those students attend U of T.

In an email to The Varsity, APUS President Jaime Kearns noted that the APUS uses materials from many campaigns promoted by CFS, including the Free Education for All, and Amnesty International’s No More Stolen Sisters campaigns — the latter of which focuses on addressing disproportionate rates of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, and trans and Two-Spirit people. Both APUS and the SCSU participated in the federation’s 2023 National Day of Action, protesting for increased postsecondary education funding.

In an interview with The Varsity, UTMSU President Gulfy Bekbolatova also highlighted the federation’s “great” campaign materials and spaces for international students. She noted that the UTMSU also uses the federation’s ethical purchasing network, which helps student unions buy ethically-sourced materials for events.

APUS members can also take advantage of the federation’s International Student Identity Card (ISIC) — a travel discount card available for free to all students who are members of a CFS union that the federation claims is recognized in more than 80 countries. APUS also purchases health insurance for its members through the National Student Health Network, which aims to lower costs for students by coordinating the purchase of health coverage.

Students pay a hefty price for the privilege of belonging to the CFS. For the 2023–2024 school year alone, UTSU, UTMSU, and UTGSU students paid a total of $1,292,909 in fees — more than a fourth of the total membership fees collected by the CFS this year. For 2021–2022 — the year in which the APUS and the SCSU released their most recent budgets — the two unions collected $352,615 in fees for CFS.

Many U of T students have invested their time and effort in the CFS. Since 2018, three U of T students — Maëlis Barre, Nicole Brayiannis, and Trina James — have held National Executive at-large officer positions, the three highest positions in the union: two from the SCSU, and one from the UTMSU. This doesn’t mention the other U of T students who have taken on other leadership roles in both the CFS and its Ontario branch, CFS-Ontario (CFS-O).

The CFS aims to connect student unions to “pool their resources and to work in partnership,” according to its website. Student unions have historically been split on how effective they’ve been. In an email to The Varsity, SCSU Vice-President (VP) External Khadidja Roble wrote that she “still valued meeting other student leaders and gaining connections with student unions across the country.”

In contrast, UTSU VP Public and University Affairs Aidan Thompson told The Varsity that the UTSU doesn’t see the CFS NGM as a learning experience. During the 2023 meeting, he said he “definitely got some perspective on the ways in which the Federation has fractured over the years, so that was interesting.”

A brief history: Should I stay or should I go?

Over the past few decades, the CFS has faced much criticism. In 2021, the UTSU published a 131-page report on the CFS–UTSU relationship that explicitly supported the union leaving the CFS, capping off years of tension between the CFS and some of its members.

In 2013, a UTGSU student who had previously served on the union’s executive committee collected enough signatures to trigger a referendum on whether the UTGSU should stay in the CFS. Although 66 per cent of those who cast their ballots voted against remaining in the CFS, the referendum was seven votes short of reaching the necessary turnout set by the CFS.

Claiming that the Chief Returning Officer (CRO) hired by the CFS to administer the referendum made unreasonable decisions that lowered voter turnout, the UTGSU argued it had left the federation. In response, the CFS sued the UTGSU.

In 2016, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice issued a ruling that the UTGSU remained legally in the CFS due to a lack of evidence showing the CRO’s decisions intended to give CFS an advantage. The judge noted that the requirement that students only cast their votes through paper ballots was “antiquated and impractical.”

The UTGSU isn’t the only student union to have been sued by the CFS after running a referendum that didn’t meet the federation’s requirements. The federation has sued at least eight other student unions who attempted to secede from the federation but allegedly did not meet the CFS’ bylaws for leaving, which the UTSU called in its report “needlessly burdensome.”

In some cases, the “litigious” — as Thompson described it — CFS has successfully legally protected student unions. In 2019, CFS-O and the York Federation of Students won a case striking down the Student Choice Initiative — a policy implemented by the Ford government that allowed students to opt out of incidental fees necessary for student unions and campus groups to function.

The union isn’t without scandal. In 2014, CFS executives received a letter alerting them to a hidden bank account held by the federation that included $263,052.80 worth of unauthorized deposits. The account was originally created to pay off debt from a CFS subsidiary. Five individuals, including two former employees, appear to have received unauthorized money from it.

Under advice from a law firm, the CFS declined to share the full forensic report on the hidden bank account in 2017. Mathias Memmel, the UTSU VP internal at the time, floated the idea that the CFS had used the money to support candidates in individual student unions’ elections.

Although the CFS has repeatedly denied involvement in local student union elections, a BC student union accused the organization in 2017 of helping pro-CFS student union candidates create campaign materials. This included the unsuccessful Change UofT slate that ran in the 2015 UTSU elections.

This time was a heyday for The Varsity’s coverage of CFS. From September 1, 2014 to April 30, 2017, we published 85 articles mentioning the CFS. Student union candidates discussed stances on CFS in their platforms, and in 2016, UTSU students launched a campaign to run a referendum on whether they should stay or go.

The news cycle moved on. Since the beginning of the 2021–2022 school year, only 12 Varsity articles have even mentioned the CFS.

However, the CFS requires that individuals collect the necessary number of signatures within six months. After six months, the petition reset before advocates could collect enough signatures, and the movement lost momentum. “Although other petitions had been organized in subsequent years, none got too far off the ground, with boundaries systemic to the CFS’ processes on decertification being a significant hindrance,” reads the UTSU’s 2021 report.

The news cycle moved on. Since the beginning of the 2021–2022 school year, only 12 Varsity articles have even mentioned the CFS.

The lack of coverage doesn’t mean the CFS didn’t change, make accomplishments, or experience scandals in those three-and-a-half years. The CFS regularly submits to the federal government, advocating that its priorities be included in the federal budget. It has revamped its Consent is Mandatory campaign and advocated against the deportation of international students targeted in an admissions letter scam.

The CFS chairperson — the highest officer in the organization — stepped down in September 2023 without any acknowledgement from news organizations. At the 2023 CFS NGM, delegates walked out of a meeting citing a decolonization audit that the organization had put off for a year, after it had committed to complete the audit in light of harmful statements made during the 2022 NGM.

The CFS continues to collect and spend students’ money. The organization spent $436,074 and $408,500 on its 2022 and 2023 NGMs, respectively. It spent $316,261 in legal costs from July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2023. The majority of those funds come from students’ pockets.

Does anyone care?

The collective memory held by university students is amnesic. Most students at U of T finish their undergraduate degrees in somewhere between four and six years. With the constant turnover, few retain the knowledge of these times past.

When I surveyed 31 U of T students, mostly from UTSG, approximately 21 out of them had never heard of the CFS. Only seven had heard of the organization and knew what it was.

“The vast majority of students wouldn’t know much about the CFS, aside from the astronomical fees that they pay each year,” Thompson told The Varsity. This in part reflects the journalistic liminal space in which the CFS exists.

Although the CFS is a national organization, its internal politics remain largely irrelevant to anyone besides postsecondary students, and most professional news outlets don’t often cover it. The Globe and Mail, the most widely circulated Canadian newspaper as of 2022, only published six stories since September 1, 2021 that mention the CFS.

Although many different university and college unions are involved in the CFS, and the decisions made by the CFS guide those unions’ advocacy and services, most student newspapers only seem to report on it when it directly intersects with their university.

The Varsity attends nearly every Board of Directors meeting held by four of the five U of T student unions. These include the UTSU, UTMSU, SCSU, and UTGSU. But the CFS doesn’t always show up on our radar. The last time The Varsity reported on a CFS NGM was 2018, and that reporting came amid the UTSU executive endorsing defederation.

In fact, I could not find any coverage of the CFS’ 2020, 2021, or 2022 NGMs by any newspapers. When I talked to six current and former student journalists who belong to the Canadian University Press (CUP) — a national organization that aims to unite student papers — only two had heard of it and knew what it was.

Ontario Institutes for Studies in Education Graduate Students’ Association President Justin Patrick noted the lack of reporting on national and international student organizations in a 2023 article he wrote for The Varsity. He argued for increased collaboration between student newspapers. He also proposed possibly creating a multi-campus student paper reporting on national affairs impacting students, but that also falls outside the normal single-campus purview that most student papers focus on.

Some infrastructure for collaboration already exists — for instance, the CUP hosts a Slack server where student journalists can communicate and share stories they’ve published.

“I think it would be good if there was more reporting on [the CFS] coming out of the pandemic and getting more of an inside view on what’s happening with this organization because the only way that it will ever change is if there’s accountability,” said Thompson.

The CFS operating policy prohibits non-student journalists from reporting on the federation’s NGM, allowing only one journalist from each student-led campus publication and two representatives from the CUP. Given that only student journalists can report on the NGMs, the CFS could also make it easier for them to do so.

I reached out to the CFS repeatedly about attending the 2023 NGM. Although CFS executive members warmly welcomed me on occasions when they answered my emails, I often had to rely on individuals within U of T student unions to share information about meetings. The CFS didn’t post publicly about when the NGM would occur.

More structurally, the CFS only allows journalists to report on the opening and closing plenaries, missing the discussion that happens in committee meetings where delegates tweak motions and determine what they will recommend the entire group to vote on. This leaves journalists and the public with an incomplete understanding of how the federation decides its direction — a direction that impacts the campaigns student unions engage in on a local level.

What happens next? You decide.

Although I’d like to believe student journalists drive the conversations on campus, I’m not so naive. In a world marked by Bill C-18, newspapers play a decreasing role in students’ lives. If newspapers are no longer driving the conversation, people will have to take matters into their own hands.

Students and student organizations have three options: accepting the status quo, where they are marginally involved with and get minimal benefit from national student movements; independently taking steps to involve themselves; or disentangling themselves altogether.

I am far from the first to decry low voter turnout and engagement or to lecture students about needing to become more involved. But I see value in reevaluating how and whether we, as students, should devote resources to this organization and taking steps to draw closer to the ideal scenario each of us envisions.

The SCSU, UTMSU, and APUS remain in favour of becoming more involved with the CFS. Bekbolatova told The Varsity that she sees the value in the CFS becoming more active on campus and receiving direct input and ideas. She said that the UTMSU reaches out to the CFS, inviting it to outreach at UTM, and hopes to get more students involved in the CFS spaces.

Roble echoed this idea, writing that she hopes to “see a greater presence across our campuses and more opportunities for general students to get involved in the work of the organization.”

As Patrick notes in a 2020 Varsity article, strong student movements in other continents have secured tangible wins for students. “I think there’s always value in an organization that unites people and that unites students, because students are very powerful,” Bekbolatova said.

Individual students do not qualify as members of the CFS and cannot vote at national general meetings. However, students can become involved in CFS Caucuses and Constituency groups even if they are not union executives.

The UTSU remains in favour of becoming less involved, for all of the reasons mentioned in its 2021 report.

“From a pure practicality perspective, the UTSU will not be leaving the Canadian Federation of Students this year,” Thompson said, citing the many barriers to defederation. However, he noted that the union’s evaluation of the CFS, as laid out in the 2021 report, stands.

“There are no services that we really take advantage of,” he said. “They have no credibility whatsoever in a lot of lobbying conversations, they’re not particularly effective when they conduct their lobby weeks, they are blacklisted by multiple parties because they’re not viewed as credible. And their organizing is lacklustre at best and woefully ineffective. So what benefits?”

The outcome I hope U of T avoids is apathy. If students pay money to and make up a fifth of this organization, I believe we should either make it better or get out.

The UTSU has chosen to become more involved with another student organization, the Canadian Alliance of Student Associations, which focuses more on lobbying. However, the union will have to decide after this year whether to formally join the organization.

Thompson told The Varsity that the UTSU will continue to focus on how to support U of T students “rather than fight major battles at a federal level,” such as trying to reform the CFS. However, he encouraged students to look into the organization and determine their own views, given the importance of students becoming involved in federal politics.

If you read this piece and decide that the CFS is beyond reform or doesn’t serve you, defederation is difficult but possible — the UTGSU got incredibly close — and defederation can only come from students. Student unions cannot prompt it.

The outcome I hope U of T avoids is apathy. If students pay money to and make up a fifth of this organization, I believe we should either make it better or get out.

One thing that I can promise you is that looking into student history can be highly enjoyable. The Varsity archives include some of the wildest shit I’ve ever read in my life, including a fair bit of scandal. Think of the best drama series you’ve watched or read, and I bet you that something crazier happened at U of T at some point in its almost 200-year history. Attending the 2023 CFS NGM was an incredibly interesting and honestly entertaining experience, and I feel lucky to have had that opportunity.

So take a moment to investigate the CFS. You can involve yourself in its campaigns through your student union; you can attend workshops and events, and ask your student representatives how they hope to coordinate advocacy on a broader scale; or, if you prefer, you can start petitions and gear up for a new campaign to leave it.

And if you get nothing else from it, you can try ranting about the CFS at your next party.