“Bell curving,” a statistical method that lumps student evaluations into pre-determined grade categories, is a common concern among U of T students. Under a bell curving scheme, course instructors choose an average grade, and then distribute class grades to get to that average; this means distributing a certain combination of A B C D and F letter grades. In most classes at U of T, the class average is around a C.

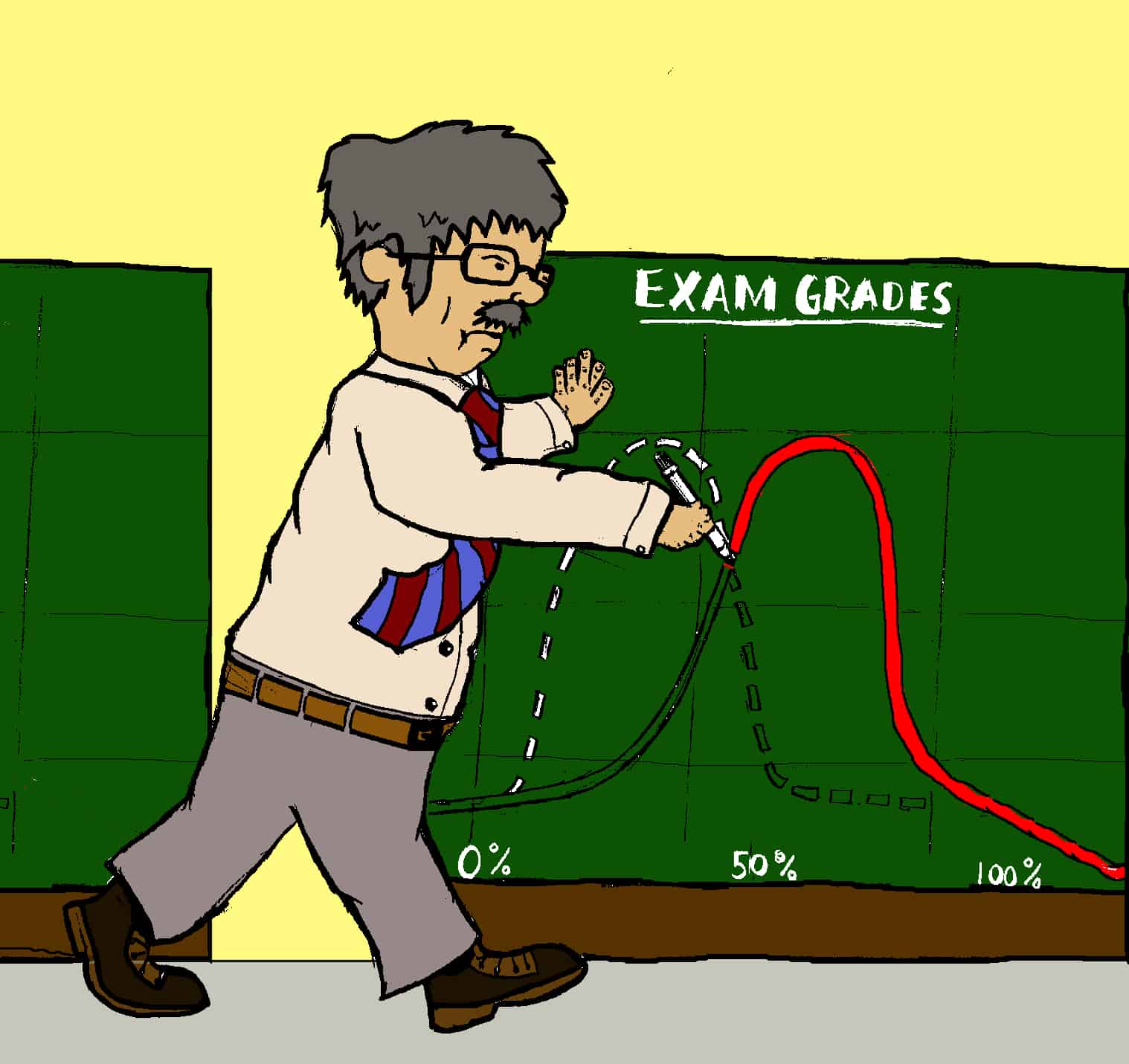

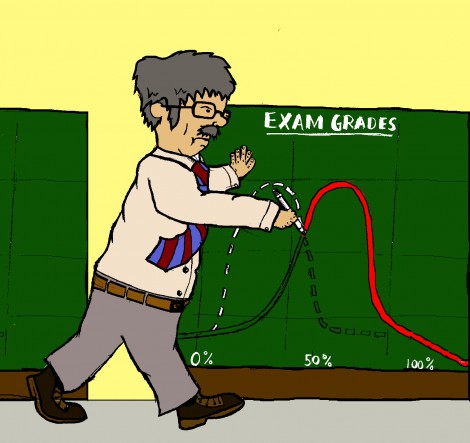

TIMOTHY LAW/THE VARSITY

University policy technically prohibits course instructors from using bell curve grading schemes — a little known fact among students. According to the University Assessment and Grading Practices Policy: “The distribution of grades in any course, examination or other academic assessment must not be predetermined by any system of quotas that specifies the number or percentage of grades allowable at any grade level.”

However, course instructors are permitted to “calibrate,” or adjust marks. According to the Academic Handbook: “Calibration is a perfectly acceptable — indeed, a responsible — practice… Calibration is the corrective process to ensure fairness in marking.”

If a test is too difficult, or too easy, course instructors are permitted to calibrate class scores. This does not necessarily require a linear manipulation — such as adding the same number to each student’s test score — so calibration can theoretically result in grade distributions that look remarkably similar to a bell curve.

When asked for comment on the calibration process, Althea Blackburn-Evans, the university’s acting director of media relations, said that calibration is necessary to ensure consistent application of grade standards across university units. “Assessments, particularly new or revised assessments, do require calibration and adjustment in terms of validity and reliability,” she said.

To that end, it is not uncommon for course instructors to calibrate class scores that do not reach a certain average. Students in BIO120 had marks adjusted upwards by two per cent on a recent test. This adjusted the mean score from 64 per cent to 66 per cent. In a note posted to the Learning Portal after the test, Spencer Barrett and James Thomson noted that the mark adjustment was made to account for technical issues. “To produce a distribution more consistent with our long-term expectations, and to make some allowance for last-minute glitches with the DynamicBook textbook system and the audio recordings, we have added 2 percentage points to each student’s score,” the note read.

Students in PSY201, a course taught by professor Ashley Waggoner Denton, also had marks adjusted upwards on a recent test. She states that the adjustment was made because the test took students longer to complete than anticipated.

Waggoner Denton, like other professors contacted, brushed off the notion that the adjustments constituted bell curve grading. “Bell curving grades is very different than bumping everyone’s mark up,” she said. “I never bell curve, and never alter marks down.”

Not all professors alter class scores; professor Derek Denis, a course instructor in the department of Linguistics, has not adjusted course grades since his first year of teaching. “Grade adjustments are sometimes necessary when instructors are trying new methods of evaluation or when instructors are new to test design,” said Denis. “Test design is a skill that comes with practice.”

Arts and Science Students’ Union (ASSU) president Shawn Tian echoed Denis’s statement. “When creating examinations, it’s difficult to gauge [precisely] how well a class will do,” said Tian, “so a bell curve after the fact may be inevitable due to some factor beyond the instructor’s control. This is especially likely when a professor needs to assess whether a new format for evaluation will be appropriate or not.” Tian also noted that he has never encountered instances of student grades being lowered after an evaluation.

“I feel students may have misunderstood the university’s stance against grade inflation, which I think is a stance [well] founded on principle, for a stance on grade deflation,” added Tian. “What one struggling student may see as an instructor being unduly difficult is really just an intellectually stimulating challenge to another.”

Mauricio Curbelo, president of the Engineering Society (EngSoc) commented on the reason test scores tend to be calibrated. “I think the biggest issue is evaluations which do not reflect the term work. This is what results in wide distributions of grades, requiring adjustment,” he said. Curbelo suggested that the university should make available to students past problem sets, tests, and exams to help avoid this problem.

According to Blackburn-Evans, the university has a number of mechanisms in place to prevent the need for grade adjustments. She pointed to the university’s Centre for Teaching Support and Innovation as an example. The centre offers workshops on course design and assessment to course instructors. Blackburn-Evans also noted that assessment and grading practices are reviewed under the university’s cyclical eight-year review. The review is reported to the Ontario Universities Council on Quality Assurance, a provincial body responsible for ensuring the quality of all post-secondary educational programs.

Correction: Ashely Waggoner Denton teaches PSY201 , not PSY220 as was incorrectly stated.