On January 16, the University of Toronto released the list of student candidates running for one of eight spots on next year’s Governing Council, the body overseeing all university affairs. As usual, however, international students are not eligible to run, causing many to repeat their calls to change the Council’s structure.

At last year’s first Special General Meeting of the University of Toronto Students’ Union (UTSU), the union’s membership called for international students to be included on the Governing Council. Numerous student governors have pledged to work on getting international students representation.

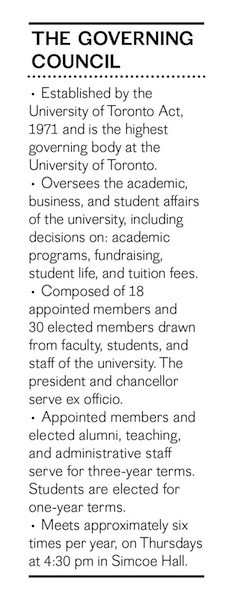

The Governing Council is composed of 50 members, including students, staff, alumni, and government appointees, and gets its authority from the provincial University of Toronto Act. The Act includes the requirement that “no person shall serve as a member of the Governing Council unless he is a Canadian citizen.” As 15 per cent of U of T students are not Canadian citizens, the requirement is controversial for many,

The Governing Council is composed of 50 members, including students, staff, alumni, and government appointees, and gets its authority from the provincial University of Toronto Act. The Act includes the requirement that “no person shall serve as a member of the Governing Council unless he is a Canadian citizen.” As 15 per cent of U of T students are not Canadian citizens, the requirement is controversial for many,

Monica Layarda, a student from Malaysia, finds the requirement ridiculous: “Every student should be given equal opportunity to pursue what he or she desires. Since the population of international students at U of T has increased substantially in recent years, they should be given access to a greater representation. I can see no real reason why nationality or citizenship should stand in the way.”

Layarda’s frustrations are shared by UTSU vice-president, internal & services Cameron Wathey, also an international student.

“I believe that we should have a democratic say in the highest decision-making body at U of T. We pay the largest tuition fees in Canada … and we’ve seen an increase of higher than 50 per cent in international tuition fees. International students should be able to participate in the democratic structure of the institution that we provide so much revenue to,” said Wathey.

Some student representatives of Governing Council are against the citizenship requirement. “I am troubled that international students don’t have a formal voice at this level of governance, given that they are a substantial and vital component of the community,” said Alexandra Harris, a graduate student governor. Aidan Fishman, a two-term undergraduate governor, also expressed concerns: “If you are a student at this university, studying at this university, paying fees at this university that are higher than those who are Canadian citizens, you have a right to serve on Governing Council.”

The University of Toronto Act, last amended in 1978, has yet to adapt to changes at the university, which explains the lack of international representation. “[An international student] who is not a citizen, in the same way they can’t serve as mayor or a member of Parliament, shouldn’t serve on Governing Council,” said Fishman, describing the rationale behind the rule. “The vast majority of governors and administrators at the university recognize that it doesn’t make a lot of sense for international students not to be represented, and there have been some legal questions about what can be done.”

Despite widespread opposition towards the requirement, little has changed. A 2010 Council report concluded that there was nothing compelling to change, and that its representation should be preserved. However, with the increase of international students and the efforts of student unions, such as the UTSU, the issue has become more apparent. Louis Charpentier, secretary of the Governing Council, highlighted the October 2013 Council, where chair Judy Goldring “initiated a process” to look into the role of international students, with the results to be released in February. Harris also highlighted a scheduled meeting between student leaders and U of T president Meric Gertler to address various issues, including the international student experience.

Any changes to the Governing Council will require provincial support. Fishman argued that the Governing Council is nervous of reopening the debate on the U of T Act.

“Especially in a minority government situation, where the government that opens legislation doesn’t necessarily have control over the final outcome of that legislation, the administration is nervous about asking for the Act to be amended, because once it’s open for debate, parties could start trying to make different impositions,” said Fishman.

In a statement, the office of the Ministry for Training, Colleges and Universities said, “We would be happy to review any proposal that the University of Toronto would like to put forward on this, or any other matter.”

Although there is widespread agreement on the need to include international students, the same cannot be said when it comes to the question of increasing the number of student seats. The UTSU promotes the view of “the more student representation, the better,” and a more proportional representation. Fishman says that while government is needed to make changes, “there is no appetite on the administration’s behalf for a Council where half the seats are student seats.”

This controversy is similar to the related issue of student representation on the Governing Council in general. Students pay a total of 53 per cent of U of T’s 2013 — 2014 operating budget, but are only allotted eight out of the 50 council seats.

“I don’t think most students, especially most undergraduate students, have the breadth and depth of knowledge to deal with those issues in the same way that professors, alumni or even government appointees might have,” said Fishman.

Elections for the 2014 — 2015 Governing Council run from February 10 to February 21.