This time of year is notorious for exacerbating mental health conditions. The academic schedule also provides many stressors — including dropped waitlists, new schedules, and the ever-present pressure to succeed academically. While U of T students are fortunate to study at a university that recognizes the significance of mental health and tries to help its students, the university’s attempts to do so have often been the object of well-founded criticism. The creation of a new Mental Health and Physical Activity Research Centre (MPARC) proposed by professors Guy Faulkner, Catherine Sabiston, and Kelly Arbor-Nicitopoulo, is a further positive step, and presents an opportunity to use the outstanding mental health expertise of our faculty and researchers to help students who suffer from mental illness.

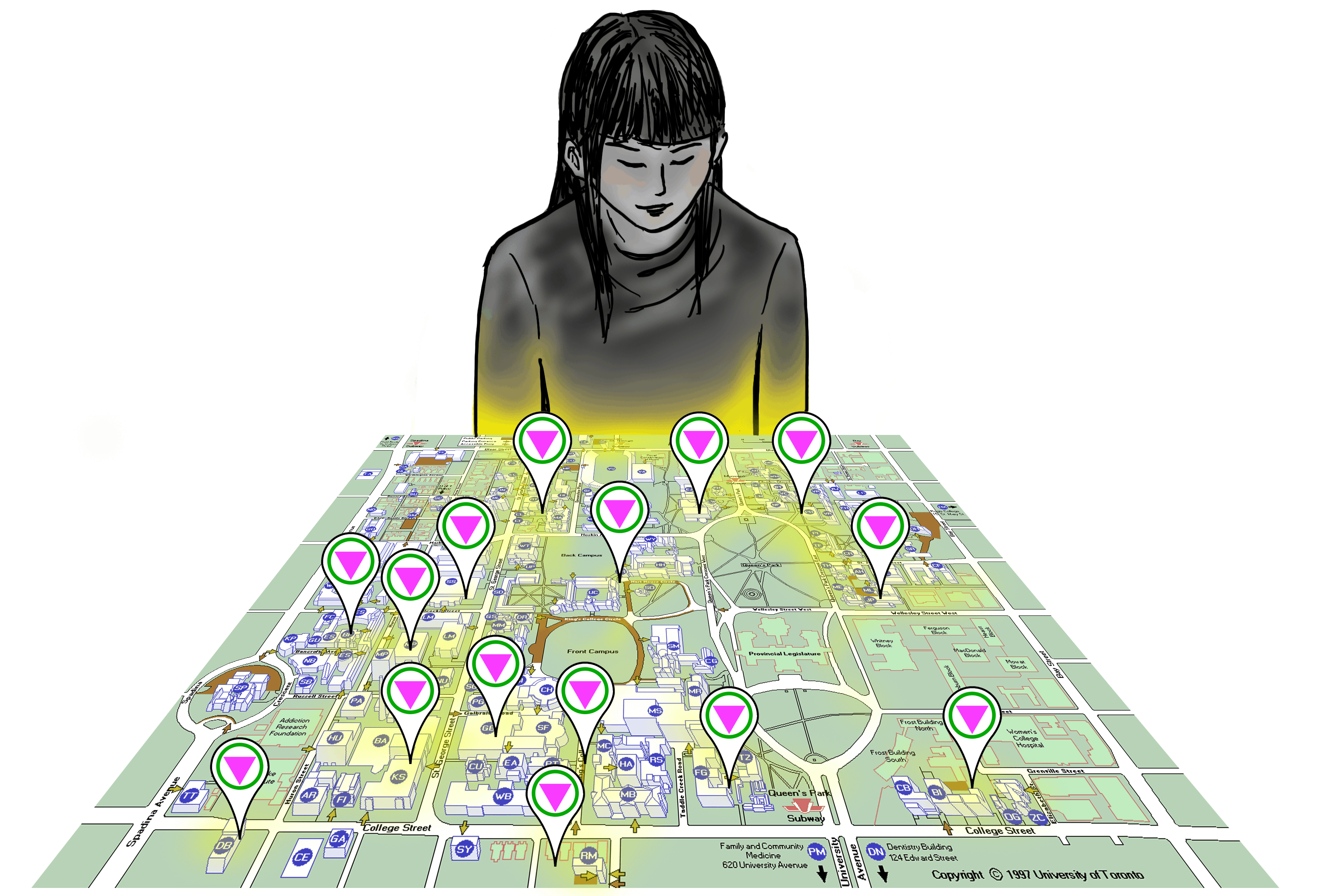

WENDY GU/THE VARSITY

To date, the university’s on-campus mental health facilities have fallen short of satisfying the accessibility needs of some students. Those who seek help through Counselling and Psychological Services (CAPS), the university’s sole facility for formal psychological counselling with practicing psychiatrists and psychotherapists, often experience long wait times before getting access to professional help. caps also limits students to a maximum of 12 sessions through the service. Although caps counsellors can direct students to external mental health resources, students have no guarantee that they will receive treatment once their allotted time at caps has come to an end. It is hard to fault the caps staff, who appear to be struggling to meet overwhelming demand with insufficient resources; the fact remains, however, that students sometimes reach out for help and do not get what they need.

The MPARC project is the latest of U of T’s endeavors to expand and improve the quality of on-campus mental health services and facilities. It is also the first to propose taking advantage of the possibilities for collaboration between the academic work being done in the field of mental health and the university’s mental health services.

The university’s unsatisfactory mental health resources have stood in sharp contrast to the high quality of research that its staff and students conduct in psychology and other fields related to mental health. This evident disparity between the landmark research conducted at the university in the mental health field and the lacklustre services that are actually offered to students is quite troubling. An institution of U of T’s calibre, which dedicates resources and time to the study of mental health, should also be able provide more adequate services to affected students.

The university has recently taken some initiative to spread mental health awareness around campus, including the “Blue Space” initiative — which promotes stigma-free spaces on campus where students can openly discuss mental health issues and seek support — and the Provostial Mental Health Committee. This committee will seek to identify gaps in the current system, particularly those involving caps — and take steps to mitigate them.

Various student groups around campus, such as Peers are Here, also act as resources for students with mental health issues, providing programming and peer support. However, the establishment of the MPARC will be the first concerted effort on the part of the university to compound research with student services.

In an interview with U of T News, Faulkner says one of his main goals is to work with “U of T students who have been wait-listed to receive specialized mental health care”; he and his team hope to “provide exercise as an intervention tool while these students are waiting to receive specialized support.” Faulkner also cites enhanced relations with other mental health facilities, such as the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) and Princess Margaret Hospital, “the capacity for large-scale, international studies,” and “ [the attraction of] top graduate students and researchers” as benefits of the project. The new centre will also encourage research into the development of mental health crisis interventions.

The decision to develop the MPARC is an encouraging sign that the U of T administration is not only acknowledging the insufficiency of the mental health care options that it currently provides, but is taking proactive and productive first steps towards fixing this problem. By enhancing its partnerships with prestigious mental health facilities in the city, the university can provide new opportunities for its own research professionals to explore. In order to serve the mental health needs of its students effectively, U of T must continue much-needed improvements of its mental health resources and should take advantage of the opportunity to combine studying mental health and helping students.