Last week, I visited Stephanie Azzarello, who — alongside Sandy Saad and Rebecca Gimmi — makes up part of the team that is working to develop and strengthen the Hart House Permanent Collection tours at the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery.

Hart House’s collection of art has been growing ever since it received its first work in 1922: A.Y. Jackson’s “Georgian Bay, November.”

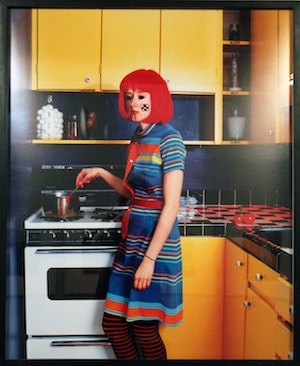

PHOTO COURTESY HART HOUSE

The gallery has always devoted itself to exhibiting Canadian art — “Canadian” being a term whose interpretation has evolved throughout the years. To date, under the curatorial direction of Barbara Fischer and the assistance of curator-in-residence Wanda Nanibush, the gallery has successfully incorporated vast Canadian identities, female and feminist art, Aboriginal and First Nations art, and art which has been created by Canadians born outside of Canada, to name a few. Just as the “Canadian” cannot be reduced to a single, concrete definition, neither can the art hung on the walls of the house. A multiplicity of identities must be embodied.

Azzarello took me on a tour around Hart House, stopping every once in a while to look at and discuss the pieces in the collection. We talked about how the Art Committee has been developing the tour’s program and its future. Azzarello shared the gallery’s plans to introduce “touch tours,” — modelled after an initiative by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMa) in New York — and sculpture tours in the spring. In order to make their vast collection more accessible to those not yet ready for docent-lead tours, the gallery’s committee has developed pamphlets listing public access rooms and the works displayed there. Self-guided tours are highly encouraged.

Despite these efforts, many of the rooms in Hart House are left inaccessible — only to be seen under the direction of docents and, sometimes, not seen at all. Docents, who are mostly students, are trained to provide factual knowledge and to encourage discourse on the art. The tours are up for interpretation and play, just as art has always been. The experience is always different. The tours provide a more intimate view of Hart House; they allow access to its history, a glimpse of its future, and we’re allowed access to things that are otherwise not so openly shared.

As we continued the tour, Azzarello and I discussed the notion of space — how we perceive things in certain spaces, and how the hanging of the art is (and sometimes is not) going to correspond to the space it is in. The art is often rotated; the committee works to showcase new acquisitions and rest others, making space for some of the 600 or so works it has acquired over the years. If you walk into the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery today, you’ll find on display in the hallway photographs of Céline Condorelli’s The Company We Keep. Condorelli’s installation can be found in various rooms of Hart House. Alongside the photographs is Lynne Cohen’s Classroom In An Emergency Measures College. Cohen explores the concept of empty spaces, photographing spaces often inhabited by people without anyone present.

Hart House is intended to be a “living laboratory.” Considering this, the Art Committee wants the art to not only reflect the life of Hart House, but also provide it with life — it lives, it grows, it is maintained, refined, and renovated.

Most importantly, it is Canadian. When considering the space of Hart House, we notice ourselves to be a crucial component. As Canadians, or as residents of Canada, we become part of the structure’s identity and purpose. Hart House embodies all things we prescribe to be “Canadian,” history, culture, and growth. As people, we breathe life into it and keep the laboratory running. The tours provided by the Art Committee allow us to glance into our own history, into the history of the house, and into the future.