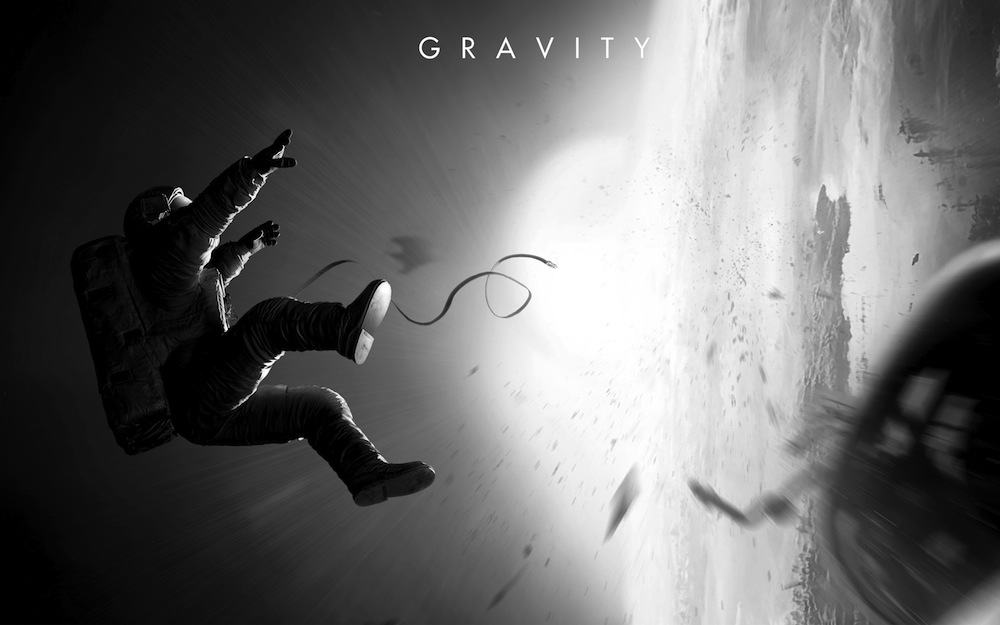

Science-related films have been under the spotlight, most recently Spike Jonze’s Her for its whimsical portrayal of the changing role of technology, and Gravity for its thrilling cinematography. Science fiction continues to be a widely popular film genre, and science and film enthusiasts alike enjoy films that balance believable science and exciting storytelling. The Varsity spoke to two professors from the Cinema Studies Institute about the intersection of science and cinema. Professor Charlie Keil spoke about the nature of science fiction and the importance of technological realism. Keil teaches several courses in the film studies department at U of T and specializes in the transitional era of early American cinema. Professor James Cahill is a specialist of French cinema who also explores the areas of experimental media and film pedagogy. He spoke with The Varsity about the coevolution of science and cinema.

The Varsity: The term “science fiction” suggests a gray area somewhere between fantasy and documentary. What does this term mean to you? Where do you draw the line between science fiction and fantasy?

Charlie Keil: It isn’t just a fictionalization of scientific ideas. Science fiction almost always involves a speculative dimension, so it’s typically in a future world where some aspect of science runs amok. One common science fiction strain is either visitation by creatures from another planet or another galaxy, or exploration of another galaxy or planet by people from Earth. If you think about it, we haven’t really done that. Yes, there’s been exploration of the moon; but now if you have a science fiction film, it usually doesn’t involve moon travel. It involves travel to some other planet or place we haven’t been to yet. That’s why I say speculative: because it’s typically not grounded in something that we are really experiencing. Most science fiction films tend to have a fantasy element, which means many of them are futuristic.

TV: Why do you think people watch science fiction films?

CK: They envision technology a few steps beyond the technology of what we have now, and that is one of the appeals of science fiction. It takes as a kind of principle things that we can recognize as being almost possible on the level of science and technology but aren’t yet being implemented. The reason that people find this notion of seeing the future depicted so interesting is because it puts to image things that you can otherwise only imagine or write down. That allows people to almost vicariously live in the future.

TV: What, in your opinion, is the benefit of scientific plausibility in films? Why does it matter to you?

CK: I’m inclined to say that if you watch science fiction with an eye to how plausible it should be or how accurate it should be in terms of its relationship to current scientific experimentation, you’re looking at it for the wrong reasons. These films aren’t conceived on that level; they don’t have to have that degree of accuracy. It’s about the whole experience, and science is simply being enlisted to engage you. People are much more likely to buy into the premise of the film if the possibility is rooted in current scientific knowledge. I think the general premise is there is to be a certain standard net in terms of a kind of adherence to what will be acceptable to an audience. People might find it laughable. But that’s about it. I just don’t think that people get caught up in that bubble in detail.

•••

Professor James Cahill is a specialist in French cinema who also explores the areas of experimental media and film pedagogy. He spoke with The Varsity about the coevolution of science and cinema.

The Varsity: One of your research interests is “the relationship between scientific uses of cinema [and] cinematic uses of science.” Could you elaborate about this relationship?

James Cahill: In many ways, the basic cinematic apparatus emerged from scientific research, particularly in astronomy and physiology, where researchers in the century began to try to use multiple cameras and then serial high-speed mid 19th photography to capture forms of movement too fast or too slow for the human eye. So the history of cinema is not just the history of commercial entertainment, of telling stories, but of a form of optical media that could be put to many different uses, of which the most popular is storytelling.

Put simply I’m interested not only in how the cinematograph gets used in scientific research—as a laboratory tool to document procedures or as an experimental instrument that enhances ways of seeing spatially and temporally— but also how scientific research and visualizing techniques may inform non-scientific filmmaking: aesthetically, technically, in terms of the stories that get told.

TV: What is the value of scientific realism in film? Is the average audience member concerned with plausibility?

JC: This is a very interesting set of questions, but ones I am hesitant to generalize about or to be too proscriptive in answering. I believe it is best to assess and judge this on a case-by-case and film-by-film basis. Ultimately context counts, as do the intentions and ends to which the science represented or mis-represented are being used and how realism itself is understood.

Films speak through and to particular ideologies; they are never innocent. For example, the bad ethology of Spielberg’s Jaws had a lasting negative influence on the popular perception of sharks, and this may have stalled efforts to gain popular support for the protection of the species. It probably inspired more people to want to kill rather than care for sharks.

In a more ambiguous manner, the loose but plausible genetic research depicted in Spielberg’s Jurassic Park may lead people to extrapolate that we can simply undo irresponsible human behavior and thus we don’t need to change it since science will always offer a fix. It speaks to the very compelling fantasy that despite the destruction of ecosystems or other irreversible changes, we can bring back lost objects or species (even loved ones!) — be they creatures that preceded humans, like dinosaurs, or animals for which we have played a role in their extinction. In a sense this is the primal, reanimating phantasy of all cinema as a technology of preservation, a luminous taxidermy if you will; what the French critic André Bazin called film’s “mummy complex.” But slightly inaccurate or imaginative depictions of scientific possibilities may at the same time spur productive imaginings about the possibilities and lines of research to be pursued. Art — or in this case popular entertainment — may inspire scientific inquiry. This seems to have been the case with the paleontologist Jack Horner, an active researcher who consulted on the film Jurassic Park, and claims that he got the idea for his present research trying to alter chicken DNA to create a “chickensaurus” from the film itself.

Your question is also a political one. Its stakes might take on further clarity if I respond to it in the form of another set of questions. What would you make of a film that offered its own creative account of real scientific explanations of global warming, the precariousness of species, or that read human culture into natural phenomena — such as the mating habits of penguins — in order to implicitly or explicitly justify or naturalize this or that way of human life or aspect of a culture? That’s one set of concerns. But compare those examples with films that might explicitly break or abuse present understandings of physics in order to propose a method of time travel and its effects — such as in La Jetée, Back to the Future, Les Visiteurs, Primer, Donnie Darko, Hot Tub Time Machine, Time Crimes, to name but a few very different films… In each of these latter examples you would have a film diverging from what you’ve called scientific realism, but I suspect the judgment regarding these scenarios is quite different and would be less about the faithful application of physics than about history or philosophy. In fact the departure from scientific realism is the condition of possibility for an inquiry of a historical or philosophical nature. Hence context is the key to assessing the question of scientific realism, which is itself a historically specific and plastic concept, continuously being refined.

TV: Is it acceptable for filmmakers to use poorly conceived science as a plot device when they know that scientifically literate viewers will have their enjoyment of the film impaired?

JC: In terms of spectator enjoyment, I suspect that the pleasures of the scientifically literate are rarely on the minds of filmmakers. To some extent this speaks to failures in public education as much as anything else — in the 19th scientific demonstration was a form of popular entertainment, but this seems far less true today. Last fall as part of the Toronto Science Festival, I helped (in a very modest way) organize a screening and panel discussion of the science in Star Trek. The panelists included the U of T astrophysicist Michael Reid and the science-fiction writer Peter Watts (who trained in marine biology), and a very engaged and erudite audience. These are people who genuinely loved Star Trek and also genuinely loved dissecting the many ways it flubs its explanations or makes grave scientific or logical errors. These two ways of watching are not necessarily irreconcilable: there is often a pleasure in critique that isn’t separate from the pleasure of a film and other media as entertainment.

Of course there is something telling, and interesting, at least to people trained in the analysis of media, in the sorts of scientific errors films make, particularly the recurrent ones, as they often say something not just about narrative convenience but about social fantasy. A rather banal example of this is the use of the “enhance” trope in crime procedurals, in films but particularly on television, where security camera footage can endlessly be zoomed into and digitally clarified in order to identify suspects or decode a clue. This is a pervasive fantasy that says as much about our ideas of photographic capaciousness, digital media, and the existence of evidence, as it does about actual technical capacities, which are far more limited. (I recall reading an article by Jeffrey Toobin in the New Yorker some years back — it was 2007 — that people who work in forensics and criminal law apparently call this the “CSI effect” for its impact on juries, who seem to believe more and better evidence is always possible). To me, these scenes are almost never convincing, but in a way, they become interesting precisely for this fact…

TV: Do the Oscars tend to assign merit to films based on scientific plausibility? Should they?

JC: The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (let’s not forget that last word) should assign merit to excellent, innovative, and courageous filmmaking, regardless of subject. Whether they actually do this is another question. Where presentations or representations of scientific information have real-

world effects or are supposed to represent actual historical situations — like a biopic about Marie Curie or Louis Pasteur — such films should be held to the highest standards of fidelity. But I honestly cannot think of an example of a film where it was specifically celebrated by the Academy for its scientific plausibility. Technical prowess and imagination, yes, particularly in the realm of special effects. Perhaps if we dug back through the short documentary category we might find one.

TV: When the film Gravity came out, Neil deGrasse Tyson publicly listed its scientific inaccuracies, and simultaneously claimed to enjoy the film. Are science enthusiasts and/or film critics genuinely bothered by implausible science?

JC: This comes back to what I mentioned earlier about pleasure and critique not necessarily being so easy to separate. Nor should we presume that all scientists, enthusiasts, or film critics share the same tastes or thresholds to which they are willing to be taken along by a film. Often a film’s artistry (or lack thereof) determines this: how skillfully the director and her team, the actors, the screenwriters, etc., deploy their craft, and in the case of a fictional film the plausibility of the events within the universe being presented, be it that of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy or Gravity.

Something I’ve learned from my own research in the history of rigorous scientific filmmaking, such as that of Jean Painlevé and Geneviève Hamon, is that the truth is almost always more interesting and stranger than fiction, and that the most striking examples of Surrealism often emerge from the context of scientific imagery and a disciplined method of empirical observation.

TV: Another common issue in science cinema comes with the introduction of technology. In the Oscar-nominated film Her, for example, an operating system is given something resembling sentience. Do you have a problem with this as a science enthusiast and a film expert?

JC: Absolutely not! In fact, I feel quite the opposite. I think one of the primary jobs of art and popular culture is precisely to experiment with and explore the issues of its time, and that, to my mind is what Her attempts. The creative geography of the film, mixing Los Angeles and Shanghai, cues attentive spectators to reading the film’s issues as both a reflection and refraction of the present: both familiar and slightly askew. The issues Her addresses — but also represses or leaves unexamined — are particularly pressing in the face of concerns regarding intelligence, surveillance, tracking, conceptions of privacy and intimacy (which are always historically determined), but also the basic question of what constitutes presence and community, what it means to be together. What I appreciated about Her was that, in spite of its melancholy, it wasn’t simply a hand-wringing cautionary tale. It explored both the alienation and intimacy enabled by increasingly sentient technologies and platforms, and credited the audience with at least some capacity to think about these issues alongside the film.

TV: Do you have any further comments?

JC: Only that I hope Professor deGrasse Tyson didn’t make those tweets while watching the film in a theatre. That would be unforgivable.

Interviews have been edited for length.