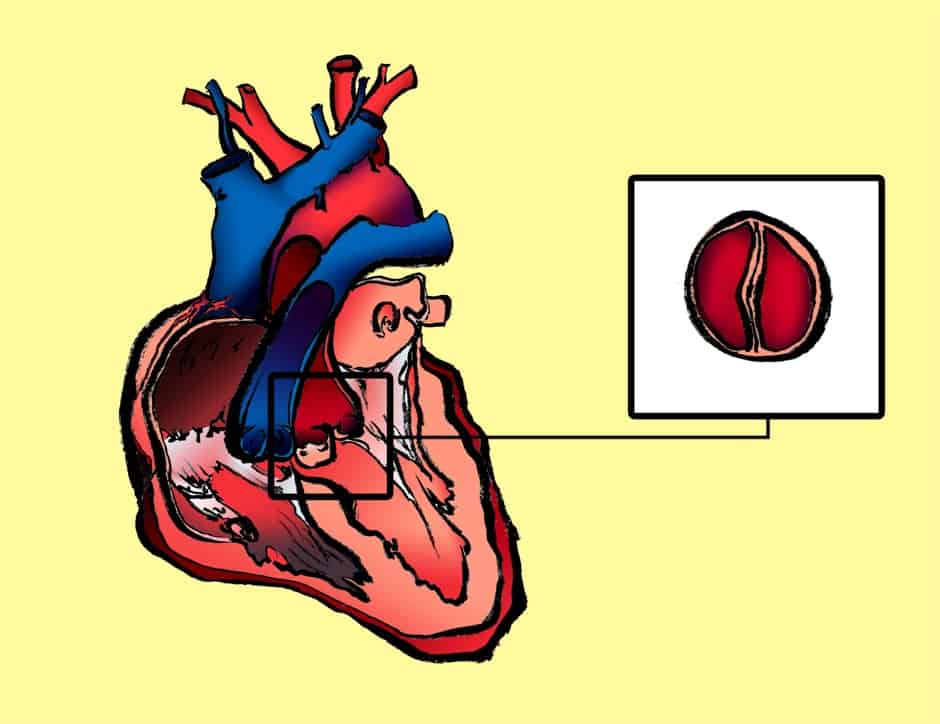

The human heart is one of nature’s most powerful pumps, supplying oxygen and nutrients to the core and extremities of the entire body. Congenital structural abnormalities can vastly compromise its function. One such defect, prevalent in 1.3 percent of the world’s population, is having a bicuspid aortic valve, that is, an aortic valve with two leaflets instead of the standard three. Cusps function to facilitate one-way flow of blood.

Physicians have known for several years that people suffering from bicuspid aortic valves are at much higher risk of developing aortic regurgitation where blood will flow backwards. Due to this, many of these people will need open heart surgery on their aorta or an aortic valve replacement. “Bicuspid aortic valve is responsible for more deaths and complications than the combined effects of all the other congenital heart defects,” says Subodh Verma, associate professor at U of T’s Department of Surgery and cardiac surgeon at St Michael’s Hospital.

Verma, who is the Canada Research Chair in Atherosclerosis, recently published a review paper in the New England Journal of Medicine claiming that having bicuspid valves puts people at a much higher risk of developing aortic aneurysms.

“The silent killer is aneurysm in patients with bicuspid aortic valve,” says Verma. He further emphasizes that it is important for these patients to be aware that they are not only at risk for valve failure but also an aortic aneurysm.

Around 50 per cent of people with bicuspid aortic valves will have larger aortas in comparison to the average population, potentially causing the increased susceptibility to developing an aneurysm. An aneurysm is a ballooning of blood vessels, usually seen with large arteries. The complications associated with aneurysms are nothing less than catastrophic; aortic laceration, where the largest artery in a body tears, leads to massive internal bleeding and often sudden death.

Aortic aneurysms can occur due to two main reasons: genetic predispositions or extensive stress on the vessel wall as a result of turbulent blood flow. The present study discusses three main patterns that result in the formation of aneurysms, with two of them not genetically linked. “There’s a subgroup in which a genetic component exists, but in the majority this is not the case,” says Verma.

Verma and his colleagues also provide insights on the optimal screening and management of this condition for better patient care. Many patients with aortic tears are often misdiagnosed with myocardial infraction (heart attack) To prevent such mishaps, people with bicuspid aortic values should be regularly monitored for aortic widening. The authors recommend that first-degree relatives of people with bicuspid aortic valves also be screened for the condition.

Even though there are no specific medications to treat this condition, certain drugs that lower blood pressure have been linked to a good prognosis.

Verma and his team are now conducting clinical trials, attempting to elucidate the efficacy of such drugs in terms of reducing the progression of bicuspid aortic valve defects.