The first store where I bought a piece of artwork when I moved to Toronto was Kid Icarus. After my initial, wide-eyed exploration of Kensington Market, I returned home to my tiny dorm room with a stomach full of churros, an ill-conceived hat, and my very own screen-printed Dan Mangan poster.

Kid Icarus has been doing its own screen-printing since the opening of its original location in 2007. Three years after my initial purchase, they invited me to stop by and watch the process in action.

The shop’s owner, Michael Viglione, has been screen-printing for decades. Owner of the former Studio Number Nineteen, he and his wife, Bianca Bickmore, eventually had enough prints to open up a retail location. The store accepts conceptual designs from various sources — including, but not limited to, independent musicians, artists, and commercial companies.

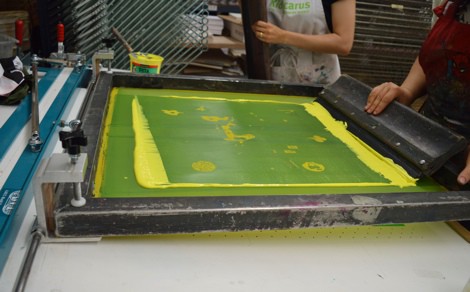

Staff member Stephanie Cheung lets me hang around and watch the process play out. Another staff member takes one portion of a future print — a stencil of a few clouds and a cartoon giraffe — and lays it on the screen. She covers the stencil and applies liberal amounts of yellow paint to the screen; then, she moves a squeegee over it repeatedly to press the image onto the paper beneath. The result is a perfectly rendered yellow image — which she then declares too dark, and starts all over again. This process is repeated many times for each of the different colours that make up any one print. The print is then put on one of the store’s metal racks to dry.

This is only a small part of the entire process. It’s certainly not the easiest way to create a poster, or any kind of artwork — especially in an era of digital printing.

“The bread and butter”

Eager would-be screen printers pay to try this process with their own hands, semi-monthly, at Kid Icarus’s Screen Printing 101 Workshop.

“We have them twice a month, usually with about 8 people, and it runs four and a half hours,” says staff member Jennifer Lee. The price is a hefty $150, but Lee says that the shop consistently sells out. When asked if the people who attend are looking to start their own screen printing business, Lee shakes her head, explaining that it’s usually artists looking to screen print their own work, or people who are simply interested in how it all works.

The success of Kid Icarus speaks to the growing interest in Toronto in both print-based goods and hands-on creativity. In a city that is home to letterpress giants such as the Mundy Brothers, letterpress printing has been enjoying a steady increase in popularity. The source of attraction for someone like me is almost certainly nostalgia — not only because letterpress printing was my first experience with art in the city, but also because it is art that I could see made in front of me, in a traditional way.

Nostalgia is also perhaps what draws different artists to the medium of print in the first place.

“Oh my goodness, yes, that’s sort of the bread and butter of the business,” says Caitlin Brubacher, another entrepreneur and owner of the soon-to-open vintage print and design shop Elephant in the Attic. Brubacher is the co-founder of Vendor Queens, a Toronto Queen West pop-up market, and is setting up Elephant in the Attic in its new home at 1596 Dundas Street West. The store currently features wares from various independent vendors across the city, but its main feature is unquestionably Brubacher’s collection of matted, framed and re-contextualized vintage prints.

Brubacher started creating and arranging prints while living in Brooklyn. “I always was a vintage shopper, and I started looking at children’s books, and I realized this art is so amazing and so under-appreciated,” she says. She adds that creating mats for the prints took over her life. When she set up at the Williamsburg market, Artists and Fleas, and stayed there for two years.

Vintage themes

A pile of vintage books is spread across a table in the centre of the room. Brubacher pours over these in search of images and inspiration for her prints, which she then arranges into different exhibits according to theme.

During my visit, she has two exhibits in place. Dread and Domesticity takes up the south-west corner of the space, and includes a wide array of prints — from 1960’s tips for housewives’ sex lives to vintage pop art. On the east side of the store, Brubacher has a table of prints simply labeled “nostalgia.” She says it’s always the first place people go when they walk in the store.

“[In Brooklyn] people would come, see a print, and they would share their stories. These are triggers for people. I can’t count the number of times people would come and cry over these prints,” she says.

Brubacher is most interested in people who come and look at the art in a more abstract, rather than literal, sense. “Something really special would happen with the nostalgia stuff — I used to call it naus-talgia, but then I had several meaningful moments and I realized this does mean something to people,” she says.

She also acknowledges that print art lends itself naturally to nostalgia. “For me, the colours are so vibrant — this is offset lithography, but oh god, letterpress is amazing. It’s just better, it’s just nicer looking, it’s just more aesthetically pleasing to the eye,” she says.

The art of craft

There are many varieties of stores featuring print art in the city, reflecting Toronto’s thriving print community. One such store, named Bookhou, is a multidisciplinary studio and store owned by husband and wife design duo John Booth and Arounna Khounnoraj. They sell items of their own creation — Booth’s painting and furniture, and Khounnorai’s textiles and sculpture. They also use screen-printing, and, until very recently, offered classes in letter press.

Toronto’s many print shops are distinguished by their individual niches. At Trip Print Press, for example, located in the Junction, Nicholas Kennedy preserves the art of letterpress with mercantile printing, and business and social stationery. Alternatively, Lunar Caustic Press, just off of Queen and Spadina, features a whole line of procedures, such as die cutting, foil stamping, and embossing and letterpress printing.

The resurgence of print-based art and style in these studios is built on both a public interest in the aesthetic of print art, and the nostalgia that seems to be tied to watching an artistic process be carried out in a manual way. Brubacher acknowledges this, and says that it is in part what drives her in her work.

“There’s something that makes you realize that simpler processes, that are harder, often create a better product,” she says, “I think that’s what people are nostalgic for. I want [Elephant in the Attic] to be like going to your local cobbler — a time where business wasn’t synonymous with corporation and people were craftspeople. The art was the craft.”