This year, undergraduates are being asked to reach even further into their pockets to pay for university.

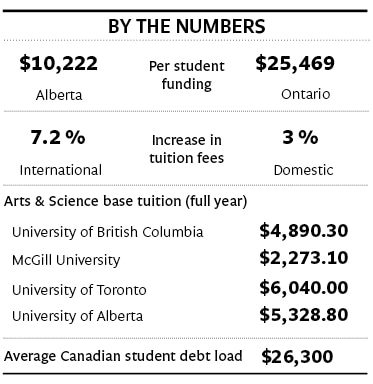

International tuition fees are set to increase by an average of 7.2 per cent, while domestic tuition fees are set to increase by nearly three per cent.

Domestic tuition fees are regulated under the Ontario Tuition Framework. Under the framework, domestic tuition fees are capped at three per cent per year for most programs and five per cent for graduate and professional programs.

However, international tuition fee increases are not covered under the framework. International tuition fee increases are at the discretion of individual post-secondary institutions.

High tuition fees are, in part, the result of federal cutbacks to provincial education funding in 1995. That year, $7 billion dollars was deducted from the capital reserved for provincial social programs, including health care and education. Nearly 20 years later, this funding has not yet been replaced.

Although the federal government continues to give financial aid to each province for post-secondary education, there is no system in place to guarantee that this reserved capital is sent to Canadian colleges and universities. Educational funding is contingent on the priorities of each provincial government, thus accounting for the varying degrees of tuition fees between each province.

Alastair Woods, president of the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS), said that this provincial imbalance could lead to a negative trend in some provinces, with potentially harmful long-term consequences.

“Government divestment is dangerous… It not only has consequences for individual students through increased student debt loads and financial barriers to attending school, but it has a broader economic effect since many students leave important decisions such as starting businesses, families, or buying a house to later in life as they attempt to pay off student loans,” said Woods.

“[T]here is a very negative ripple effect of tuition fee increases that damages not only individual prospects, but the economic health of our communities,” he added.

Undergraduates in Ontario are at the largest disadvantage. Over the past 20 years, the province held the record for the lowest per-student funding, with its average education capital reserve around 24 per cent below the national average. Ontario also has the highest post-secondary tuition fee rates in the country.

Althea Blackburn-Evans, U of T director of news relations, attributed rising tuition fees to provincial government underfunding. “The Government of Ontario provides this province’s universities with the lowest level of per-student funding in Canada — by a wide margin. Provincial grants have remained flat the last few years. This means Ontario universities, including the University of Toronto, must rely increasingly on tuition revenues,” Blackburn-Evans said.

According to May Nazar, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Training, Colleges, and Universities, the provincial government increased funding to post-secondary institutions by 83 per cent over the past 10 years. Per-student funding for universities increased by 29 per cent over that period.

Nazar added that Ontario has one of the most comprehensive student financial aid programs in Canada, with over $1.1 billion in grants and loans given to students each year.

“Investments in student financial assistance over the past 10 years have resulted in more than double the number of students qualifying for aid, while enrolment has increased by 40 per cent,” she added.

“Tuition fee increases are simply unethical,” said Yolen Bollo-Kamara, president of the University of Toronto Students’ Union (UTSU), adding: “Our peers at UBC and McGill are paying $4,890 and $2,270 respectively for Arts & Science programs while we are paying $6,040.”

According to Bollo-Kamara, the situation is even worse for international students. “At the University of Toronto, our international students pay the highest tuition fees in the country, and do not have the same access to services and healthcare that domestic students have,” she said.

In 1994, Ontario disqualified international students from the Ontario Health Insurance Program (OHIP).

“I feel like I’m in a violent circle of debt,” said Rebecca*, a third-year archaeology and religious studies major. “I initially went to school to get a degree so I can have a higher paying job after I graduate, but I feel unprepared for life after U of T. It seems [that] for social science and humanities students, there is no other option but further education, which means more debt,” she added.

Before attending university, Rebecca, a mature student, spent three years saving money for her time at U of T, only to have spent it all in the first two years on tuition and course materials. She now has no choice but to apply for OSAP.

Before attending university, Rebecca, a mature student, spent three years saving money for her time at U of T, only to have spent it all in the first two years on tuition and course materials. She now has no choice but to apply for OSAP.

While many undergraduate students view student debt as a questionable burden, some see U of T’s high tuition as justifiable.

“Tuition is ridiculously high, but in a way you are paying for the name of the university,” said Peter*, a fourth-year pharmacy student, adding: “U of T has a prominent global reputation that in turn, we pay to be associated with. The university also provides a lot of services and benefits that students are free to take advantage of.”

Bollo-Kamara called on U of T students to mobilize and influence provincial government policy.

“We should respond by mobilizing against these increases and telling our government we simply will not accept this any longer,” said Bollo-Kamara, adding: “Our opposition in the form of petitions, lobbying and rallying to defeat flat fees led to a change in the tuition fee billing structure that is saving some students over $2,300 per year. We need our government to invest in our society’s future, and if we need to take it to the streets to make that happen, then that’s what we should do.”

Nazar said that tuition fee figures used by Statistics Canada for Ontario are not entirely comparable with those in other provinces, due to data limitations and differences in the structure of postsecondary education systems across Canada.

“Indeed, PSE systems vary widely among provinces and territories. One reason is that the mandates of colleges differ widely. In Ontario, colleges focus on labour market oriented programs whereas in some other provinces…colleges often act as university feeder institutions, delivering the first years of degree programs,” she added.

According to Blackburn-Evans, U of T provides the most generous financial assistance of any Ontario university or college. Nearly half of U of T undergraduates are eligible for OSAP. On average, these students pay less than half of the university’s full tuition cost.

According to the university’s Policy on Student Financial Support, “No student offered admission to a program at the University of Toronto should be unable to enter or complete the program due to lack of financial means.”

On March 28, 2013, the Ministry of Training, Colleges, and Universities issued a new four-year Tuition Fee Framework policy. The previous framework, instituted in 2006-2007, capped the overall yearly tuition increases for domestic students at 5% and included an accessibility guarantee that assured a specific amount of government funding was set aside to help low-income students fund their education.

Under the new framework the accessibility guarantee remains in place, but the fee increase is now capped at three per cent for domestic undergraduate students.

Prior to the Tuition Fee Framework revision, the provincial government upgraded OSAP by initiating the Ontario Tuition Grant (OTG), a program that awards low-income students a non-repayable grant of at least $840 per term.

*Name changed at student’s request.

Correction: A visual in this article incorrectly states that per student funding in Alberta is $10,222 and per student funding in Ontario is $25,469. In fact, per student funding in Alberta is $25,469 and per student funding in Ontario is $10,222.