Upon arriving in Nepal, the three of us, University of Toronto medical students, realized that the situation that we had been placed into was going to be vastly different than what we had expected.

We were volunteering for a charity devoted to improving children’s health in Nepal.

Last summer at a nutrition outreach camp in a remote community high in the mountains, our hands were covered in urine as we measured the height and weight of 1,300 Nepalese children. But then again, nothing about our experience turned out the way we thought it would.

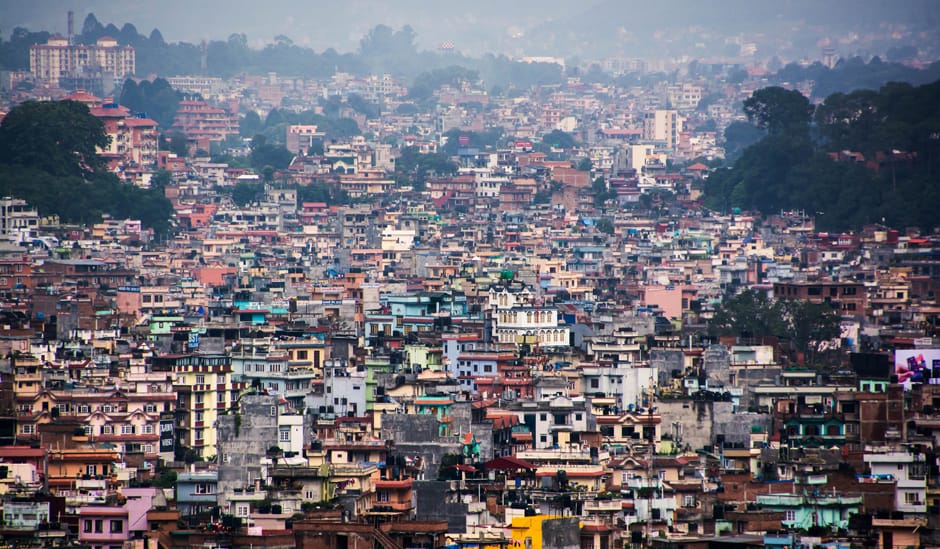

We applied to volunteer for BABU (Bringing About Better Understanding), a charity focused on improving children’s health in Nepal. We would be involved in improving the Nutrition Centre at the International Friendship Children’s Hospital (IFCH) in Kathmandu, which ran a two-week nutritional rehabilitation and education program for malnourished children and their families.

Challenge ONE: what are we doing here?

Less than a month before we left Canada, we learned that the Nutrition Centre, the hub of our future project, was being threatened due to a lack of funding. Our initial project had ended before we had even arrived.

In retrospect, this was a blessing in disguise. It allowed us to start from scratch, spurring us to think about a type of project that would benefit our target population, and more importantly, would be sustainable; that is to say, a project that would continue without us once we left Nepal.

Improving the health of a malnourished population through bettering their nutrition was always our primary objective. So why should that change? All we needed was an alternative solution to reach that goal but, once again, funding remained an obstacle.

The Nutrition Centre at BABU was fortunate to receive funds from both EarthTones, a yearly benefit concert at U of T, and a self-initiated fundraiser we hosted for friends and family.

Although these funds gave us a head start on creating a new way to realize our goal, we had to be extremely frugal in spending what we had.

Challenge TWO: different Cultures

Living in Toronto, we were accustomed to a fast-paced, high-stress environment. When faced with a challenge, our instinct was to troubleshoot, marshal our resources, and solve the problem as quickly as possible. This type of Western urgency is the antithesis of Nepali culture.

It was from our experience at the outreach camp, and learning from the locals that we discovered the true needs of the community, and how to cater our nutrition initiatives to those needs.

At IFCH, we worked alongside an amazing physician, Dr. S. — a short, wide-eyed, and big-hearted Nepalese doctor. As head of IFCH, this man showed dedication beyond what we thought was possible. He had not taken a single day off work since starting the hospital over a decade ago.

Most importantly, he supported our initiative to implement better nutrition at the hospital. Although it took us over two weeks to come up with a project idea, we decided to make “ready-to-use therapeutic food” or RUTF for short, which we would give to malnourished children free of charge, for a two week period with the aim of weight gain and achieving better nutrition.

Challenge THREE: Passing the torch

We created a robust, easy-to-follow protocol so that our project could be run for a full year. We trained medical students, nurses, and made a partnership with Dr. Shristi — a smart, young energetic doctor who would take on the project after we left. Her goal was to run a study that would help promote the hospital, and educate others on the importance of malnutrition research.

There has been a lot of criticism about so-called “voluntourism” and short-term global health projects. In taking on this kind of work, you need to be comfortable with the fact that you are not going to save the world in a month. You need to be flexible, adaptable, and open to change.

It is important to never lose sight of why you are there, and know that even if things seem frustrating at times, the smallest of successes do make a difference to someone. You are one player on a much larger team, and without laying down the soil, and getting your hands dirty in the process, nothing will ever grow.

Laura Betcherman, Kira Bensimon and Samantha Kay Dunnigan are all second year medical students at U of T.