It’s a busy time of year for the AGO. Gallery visitors are rushing the temporary exhibits, Colville and Michelangelo, before they leave in the weeks ahead. The lines last Friday afternoon were the longest I’ve ever seen there, winding out the door and creating a frenzied excitement.

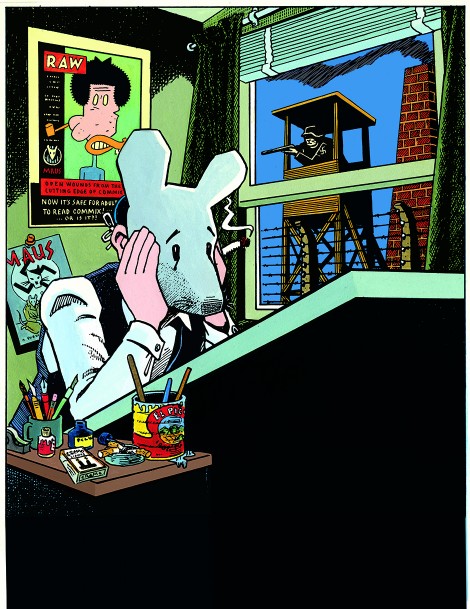

I was there for Art Spiegelman’s CO-MIX: A Retrospective, a modestly advertised but far more dense exhibition showing until March. Tucked away in one of the gallery’s quieter corners, the exhibit showcases Spiegelman’s lifetime of work and his evolution as a graphic novelist.

Spiegelman was born in Stockholm in 1948. He was the child of two Polish Holocaust survivors. By age 15, he had immigrated to New York with his parents and was attending the High School of Art and Design. As a young teen he also began to produce his first comics, and his work started appearing in underground presses.

Organized chronologically by the phases of his professional life, the exhibit provides a sweeping catologue of Spiegelman as an artist — his stylistic changes, his influences, and his collaborations. His early work is now known as “underground comix,” part of a movement that began as a counterculture statement discussing issues of sex, drugs, violence, and politics. The Comic Code Authority, an industry regulator, had previously banned these topics in standard comics.

EVOLUTION AS AN ARTIST

An early comic on display was called Pop Goes the Poppa, which depicted a detective story about a father who had been mysteriously shot. The man standing next to me in the exhibit read the comic from a few short inches away, staring intently in silence, before suddenly bursting into belly-shaking laughter.

This kind of a reaction typifies much of Spiegelman’s work; deep themes depicted with wild and exaggerated reactions, and a dark humour that resonates with many. In 1973, he published Prisoner on the Hell Planet, which told the story of his mother’s suicide — his first departure into more serious subject matter and personal narratives.

He began to focus increasingly on visual and narrative structures, plot progression, passage of time, conventional speech, and narration. Eventually he published an anthology of work up to the late 1970s, called Breakdowns. The title was an ode to the technical name of panels in cartooning, as well as his mental state during much of its creation — he had been briefly institutionalized nine years before.

Also starting in the late 1960s was his freelance work for the Topps Chewing Gum company, which would support him for 20 years. Seemingly much lighter than his personal subject matter, he would create the concepts for bubblegum, trading cards, and stickers.

MAUS

Spiegelman’s next major project was 13 years in the making. Maus is a two-part graphic novel that describes the experience of Spiegelman’s parents’ lives during the Holocaust and his fraught relationship with his father. His initial conception of such a project was “a very long comic book, that needed a bookmark and would be worth rereading.”

Maus gave Spiegelman the loyalty of many, many fans. Published in two parts in 1986 and 1992, it was fundamental in the establishment of the graphic novel genre, and is the only graphic novel to have ever won a Pulitzer Prize. The exhibit focuses on all of his works and the way they fit together, but nevertheless grants Maus the two biggest wall spaces. Its impact was undeniably transformative and shockingly powerful.

After Maus, Spiegelman turned to comic essays as a form of journalism, one of the most interesting periods in his career. He would write essays and reviews for publications like the New York Times Magazine and, later, The New Yorker.

IN THE SHADOW OF TWO TOWERS

On September 11, 2001, Spiegelman and his wife Francoise Mouly were living in Manhattan and ran to collect their daughter from her high school, several blocks from the World Trade Center. The second tower fell behind the family as they raced away.

This experience would become a new focal point for the artist; for the next three years he dropped all other commitments to create In the Shadow of No Towers. Most newspapers and magazines in the United States refused to publish his broadsheet comics, looking to avoid Spiegelman’s “critical voice and overtly political content.” The Jewish Daily Forward was the only publication to run the collection outside of Europe.

Ultimately, Spiegelman’s collection shows his power as an artist. Above all else, it makes you think — I had never learned so much about so many topics within one exhibit. The experiences depicted and stories told are at once personal and collective, with Spiegelman’s honest voice striking a nerve amongst many readers. The artist himself summed it up best: “Spiegel means mirror in German, so my name co-mixes languages to form a sentence: Art mirrors man.”