Heart disease and stroke are two of the three leading causes of death in Canada. Cardiovascular diseases have a huge impact on the Canadian economy, resulting in annual costs of more than 20 billion dollars in health care services, hospital bills, lost wages and decreased productivity.

Researchers from McMaster University and the University of Toronto collaborated to conduct a large-scale randomized controlled trial investigating treatment strategies for cardiovascular diseases. The study provides evidence for increased risk of stroke associated with routine blood clot removal after a heart attack.

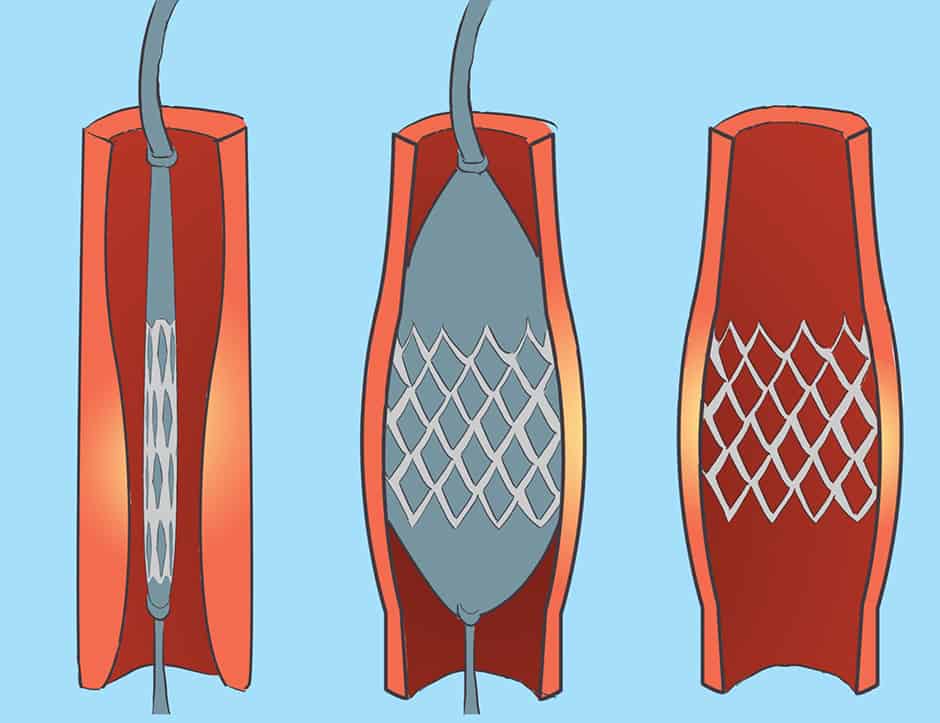

Supported by previous research findings, thrombectomy has been used to remove blood clots prior to opening up a blocked artery through percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). During PCI, a deflated balloon is inserted into the narrowed artery and subsequently inflated to allow blood flow. This is followed by stent deployment to keep the artery permanently open. While PCI is a non-surgical procedure, thrombectomy is the surgical removal of a blood clot.

Previously, thrombectomy was used in emergency situations with the failure of PCI in a procedure called bailout thrombectomy. Practical guidelines were recently altered to implement routine manual thrombectomy with PCI. Clinical practice of routine blood clot removal serves to improve blood flow and reduce chances of distal blockage of vessels. However, several recent clinical trials disagree on the benefits of this procedure.

The total trial aimed to contrast the efficacy of PCI coupled with thrombectomy and PCI alone in patients following heart attack. Unlike earlier studies of its kind, the total trial was much larger, leading to greater clinical significance. Over a period of four years, a total of 10,732 patients enrolled at 87 hospitals in 20 different countries were involved in the clinical study.

The results of the trial do not support the use of routine manual thrombectomy. When compared to PCI alone, routine blood clot removal did not reduce the risk of cardiovascular death, recurring heart attacks, cardiogenic shock, or heart failure within 180 days. These benefits were also absent in patients with greater clotting, further questioning the efficacy of routine manual thrombectomy. Instead, the clinical practice of thrombectomy was associated with higher rates of stroke as seen among patients who underwent both PCI and thrombectomy.

Authors of the study hypothesize that stroke rates measured within 24 hours after the procedure would increase in the thrombectomy group. This hypothesis is based on the assumption that stroke following thrombectomy is due to blood clots breaking off and travelling to brain vessels or air present in the brain during the procedure. While the findings support the initial hypothesis, the results of the trial also indicate continual increase in rates of stoke between 30 and 180 days after the procedure. The authors struggle to explain the significance of this finding and are unable to rule out the role of chance due to the small number of occurrences.

“We did not design the trial to test the effectiveness of selective or bailout thrombectomy,” said Dr. Vladimír Džavík, the study’s co-principal investigator and professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, in a news release from McMaster University. “Thrombectomy remains an important treatment when the patient’s blood vessel is still filled with blood clot when the PCI procedure is done, or if it cannot be completed successfully because of the clot.”