Hypertabs is The Varsity‘s online features subsection about all things Internet. Our goal is to explore the depths of the online world and understand how it shapes our habits and affects our communities. You can read the other articles included in this project here.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]wice a year, I find myself checking my e-mail a bit more than usual. In December and January, I check Outlook incessantly expecting messages from professors informing the class that final marks are available online; and in April and May, the confirmation of summer prospects drive my anxious inbox refreshing.

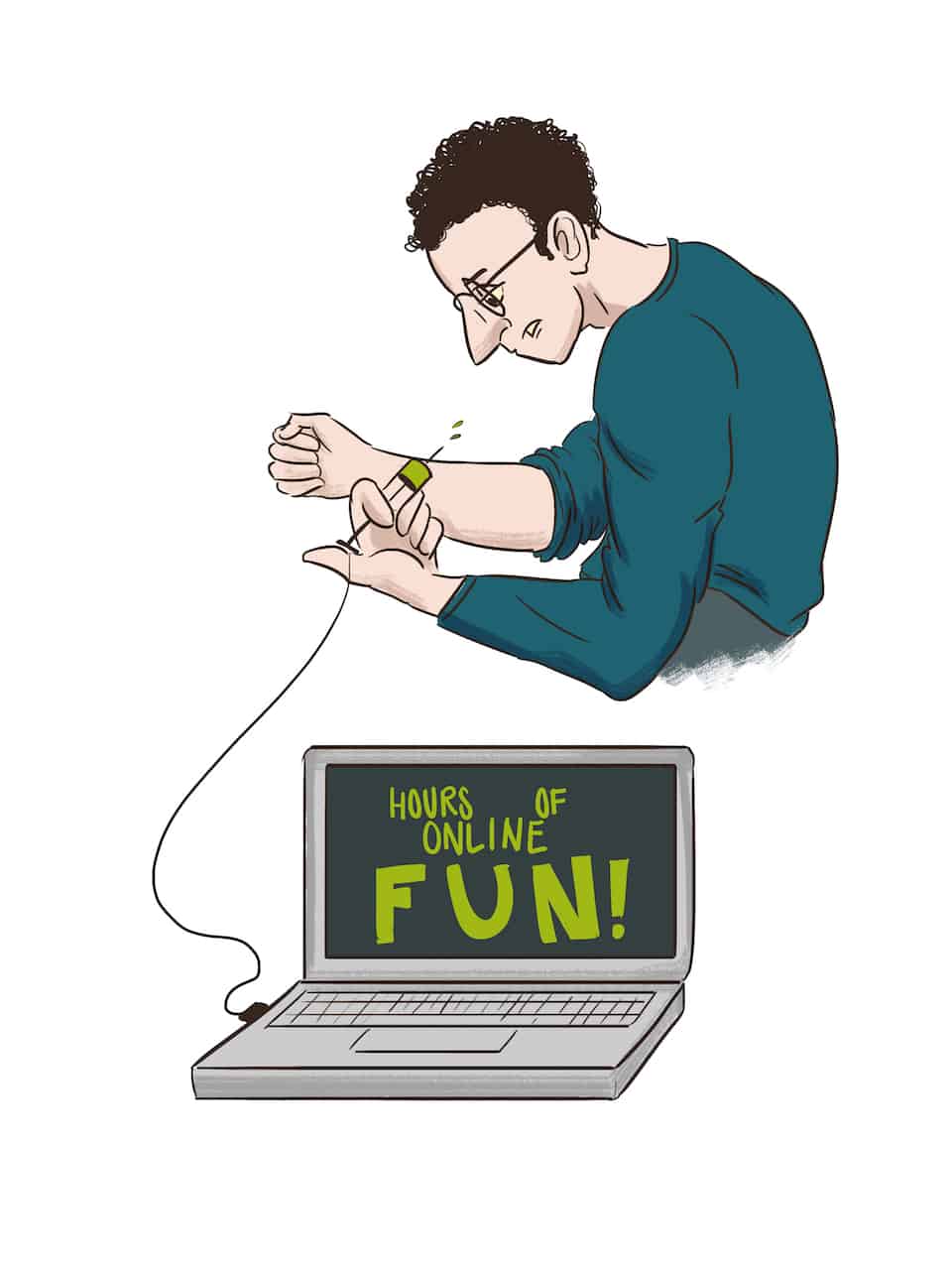

I am fully aware of how ridiculous this neurotic activity is; checking my email will not make anything happen any faster. Interestingly, it occurred to me recently that my compulsive behaviour has only been made possible by the birth of Web 2.0 – a new term coined to define the transition from what was previous a mostly ‘passive’ interaction with the Internet to the interactive and user-generated experience brought about by innovations like social media. The recent over-development of the ‘refresh-impulse’ has enabled, if not aggravated users’ impatience and neuroticism online, and it leads us to wonder: is this obsessive behaviour innate, or are we simply victims of the Internet?

In this country, much like almost everywhere else in the world, the Internet has reached a critical ubiquity. In fact, Canada leads the world in sites visited and time spent per person on the Internet. As students, we use it for research, communication, and, of course, procrastination. Sometimes this can go beyond just spending half an hour too long scrolling through Twitter. Whether it’s gaming, social media, pornography, or e-mail, the Internet is a space where addictive behaviour can flourish.

Digital Damage

Hyacinth*, a first-year life science student, likes to watch videos on the Internet as a way to take a break from studying. Sometimes, the break becomes a binge. “Part of me thinks it is good for stress relieving, the other part tells me that is bull crap, sleeping more is better for that. I wake up [for a] test the next day feeling tired and fucked up. Never again… or so I think.”

Internet addiction is not based solely on how long one uses the Internet, it is also influenced by the extent to which the Internet disrupts daily routines, relationships and health. James, a fourth-year engineering student, regrets his overuse of the Internet. “Surfing the Internet is all I did after I came home from [high] school… As a result, I have very few useful skills and competencies today. I’m starting to change that now, but I’ll never get that time back,” he explains.

“If I study, I need Internet. It is hard not to be distracted while doing real work, it is always there luring me,” admits Hyacinth. “When I open my laptop for studying, I have this procedure [in my] memory that makes me open [Google Chrome] and click reddit, since I have been doing it so often.”

Wasting time is not the only problem. Over dependence on the Internet is routinely linked to health concerns including: obesity, headaches, carpal tunnel syndrome, changes in sleeping patterns and shrinking of brain tissue. While all those symptoms are undesirable, the last one seems the most frightening.

The shrinking of brain tissue is connected to online gaming addictions. In a study of university aged Chinese students with online gaming addictions, researchers found that gray matter in the brain’s cortex — where speech, memory, motor control and emotions are all processed — shrunk by as much as 10 to 20 per cent. The longer the behaviour persisted, the more tissue was lost.

Interestingly Karl Friston, a neuroscientist at University College London, says that brain tissue shrinkage is not necessarily a bad thing. He argues that it could be a result of the brain adjusting to a frequent habit and optimizing itself to perform certain tasks. For example, a study of taxi drivers found a similar shrinkage sometimes called densification, in brain tissue due to better developed spatial navigation skills. While this may not seem so dangerous, white matter in the brain — which links different regions –— was also shown to be affected by gaming addictions. Addicts’ brains often had reduced white matter, which adversely affected short term memory and decision making. Additionally, a German study found that people who used the Internet excessively exhibited gene mutations similar to those found in smokers.

While there is no question that excessive Internet use can be detrimental, experts in the world of psychology are divided on whether it constitutes an addiction — and if it is, what should be done about it.

A Question of Legitimacy

In 1998, a psychologist named Kimberly Young developed the Internet Addiction Test (IAT), a set of 20 questions that ask participants to measure how often they use the internet on a scale of zero (never) to five (always). According to the test, the higher the score, the stronger the subject’s addiction, although it is not without its critcis. Dr. Young believes that problematic Internet use (PIU) – an accepted term for damaging Internet use — does constitute an addiction, and she is not alone. Dr. Ofer Zur, a licensed psychologist, agrees, and has documented what he understands as the stages of Internet addiction. Dr. Young’s test is still seen as the gold standard for measuring Internet addictions, though it is not without its critics.

Skpetics of Internet addiction include Dr. John Gohrol, the founder of Psych Central, a mental health social networking tool. Gohrol, who has described Internet addiction as a “fad disorder,” has lambasted research in the field for bias and inconsistency. Others have argued that, while PIU is an issue, it is not an addiction. They fear that calling PIU an addiction could lead to unnecessary medication and pathology of all behaviour relating to internet use.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) currently considers online gaming a disorder, but, citing a lack of research, excludes surfacing the web as a definable addiction. Internet addiction, because it is behavioural, is difficult to define. So far, gambling is the only behavioural disorder in the DSM-5; the rest are related to substance use.

Many experts believe that Internet addiction has little to do with the Internet itself. Some researchers see it as a symptom of social anxiety, depression, fear of missing out, and obsessive-compulsiveness. Dr. Bruce Ballon, an associate professor at U of T’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health and director of the Internet addiction program at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), identifies underlying psychiatric problems in his patients and tries to solve those, instead of addressing internet habits themselves.

Providing a different perspective, freelance writer Michael Shulson suggests that the Internet is designed for compulsive use. Many websites, especially publications born in the digital age – think Buzzfeed, Gawker, and Upworthy – making their money from page views and clicks. Writers, publishers and advertisers alike benefit from maximizing exposure to these web pages. These sites — often arbiters of the infamous and ubiquitous clickbait that clogs our social media feeds — depend on constant scrolling, link clicking and page sharing. In fact, strategies attempting to capitalize on this behaviour are becoming normalized. Nir Eyal, a consultant working with several Silicon Valley firms, wrote a book called Hooked, teaching web designers how to give their sites “narcotic-like properties.” Eyal does exhibit some discretion; he refuses to consult for pornography and gambling sites, and his book has a moral rubric to encourage ethical behaviour. Some readers of Hooked might take Eyal’s ethical suggestions seriously, while others will use his tips and tricks to manipulate and entice visitors into visiting their own sites.

Shulson’s theory that the Internet, as a platform, has addictive qualities, seems convincing. It has made bingeing easier and normal. Pornography and gambling can be addictive independent of the Internet, but it makes them easier to access. With the web, you don’t have to stop gambling when the casino closes, and money seems more disposable when it’s bet online. The Internet has created a space for millions of free porn videos and photos, eliminating the need to spend money on a dirty magazine or adult video. Netflix has led the charge on bingeing with its automatic progression from one video to the next. Facebook has followed suit, implementing a video feed that automatically plays several similar clips after watching one video. This phenomenon extends past entertainment and recreation, after all, the internet is always open, allowing impatient students like myself to check our email relentlessly, and ambitious executives to work far past office hours if they please.

Although definitions and designations are undecided, it seems conclusive that the Internet can foster destructive behaviour. Cures and solutions have so far manifested in several forms.

Regaining Ctrl

The fight against Internet addiction, traces its roots back to an area among the worst affected: East Asia. In as early as 2005, 40 per cent of Hong Kong’s youth were addicted to the Internet. In 2009, China had over 400 clinics that treated Internet addiction. South Korea implemented the radically unpopular and euphemistically named Cinderella law in 2011. South Koreans under the age of 16 are “Cinderella,” and the South Korean government serves as the Fairy Godmother, using “magic” to block Cinderella from accessing gaming websites after midnight. The law still applies, but it was eased in 2014.

Countries all over the world have followed East Asia’s example in the battle to curb Internet addiction. There are self-help software solutions like Freedom and Cold Turkey, which allow users to block certain websites at specific times, as well as institutions focused on therapy and rehabilitation. North American approaches usually cost tens of thousands of dollars for treatment. Notable Internet addiction recovery centres include reSTART, in the state of Washington, and Outback Therapeutic Expeditions in Utah, which, for a cool $25,000, provide therapy in the form of a digital detox. Canadian institutions are few, with only the Hôtel-Dieu Grace Healthcare centre in Windsor joining the efforts of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). Unlike the costly American programs, Hôtel-Dieu Grace offers a free inpatient program for 21 days.

Life Behind a Screen

For students, social networks are nearly a necessity. They allow us to keep in touch with faraway friends, relax, read news, network, and collaborate with classmates. All of these factors make it difficult to curb compulsive use. Even if one intends to visit Facebook only to post in a course group, there’s a good chance of being distraced by something unrelated. Anything from a headline to an embarrassing photo can be the beginning of an Internet binge: an indulgent but ultimately regretful spree of scrolling, hopping through hyperlinks and amassing an army of tabs, all to wonder where the time went at the end of it.

Many websites, including smaller social media sites, allow people to log in with Facebook or Twitter. Moreover, social media widgets encourage users to share content with their friends. So, not only does social media provide access to its native networks, it allows easy access to the rest of the Internet. It’s possible to ignore social media altogether, but its seductive convenience is too alluring for most.

In 2011, 86 per cent of Canadians between the ages of 18-34 had a social media profile. It makes sense: why would anyone forgo a digital world where you can talk to friends, read the news, watch videos, and publish your thoughts all in one place?

Hyacinth argues that interaction is easier on the Internet. “Clubs are fun, but their [hours are] usually inconvenient. It is easier to spend 30 minutes on Reddit while studying, than to go out and hang out with friends.” For all its benefits, it seems obvious that social media could never recreate the intimacy inherent to face-to-face contact. Cute emojis are no substitute for hugs and kisses, and online communication — where people toil over the perfect status update and carefully curate their profiles — strips users of authentic interaction. Hyacinth tells me that he will probably rely on the Internet less when he makes more friends, but I cannot help but wonder how people can go about making more friends when they spend most of their spare time online.

Internet addiction is clearly a difficult problem to solve. The Internet has made life easier in many ways, and has become a key component of our lives. This makes it both difficult to avoid, and even more difficult to identify where it transitions from being a part of life to controlling one’s life. It’s fluidity blurs work and play, socialness and anti-socialness. Smartphones, tablets and computers make it almost as omnipresent as the air we breathe. How do we manage?

Perhaps our best hope is to Google it.

*Name changed at student’s request