The opening reception of the Blackwood Gallery, with its many film screenings and talks planned throughout the year, is sure to excite lovers of fine art.

On the night of its opening reception, the gallery, located in UTM’s Kaneff Building, gave visitors an opportunity to view its latest exhibition, The Day After, by Maryam Jafri. The exhibit is a historical collection of photographs taken between 1934 and 1975 across Europe, Asia, and Africa.

As Jafri explains the intention behind this collection is to show how “post-colonial states in Asia and Africa [and Europe] preserve the founding images of their inception as independent nations.” The selectively chosen photographs aim to draw attention to marginalized historical events; in a way, the exhibition gives the viewer a unique opportunity to see a side of history not seen in textbooks.

What’s also impressive is the amount of collaboration and research conducted by Jafri and Bétonsalon Centre for Art and Research in the production of the exhibit.

A team of archivists, researchers, and journalists worked with Jafri to attain the images. The National Library of the Philippines, Mohamed Kouaci Archives, and Kenya Ministry of Information are just a few sources from which the collection stems from.

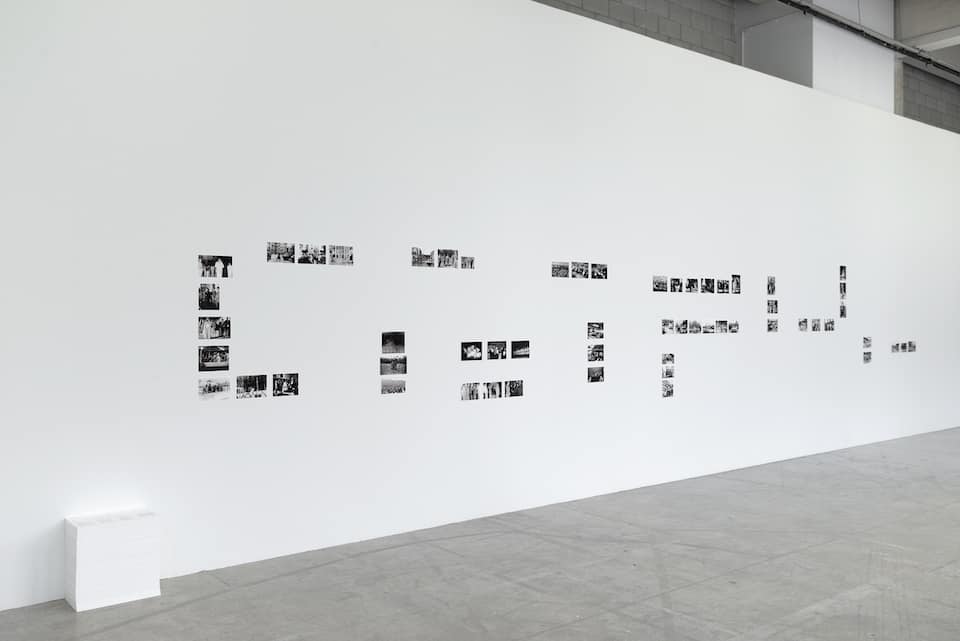

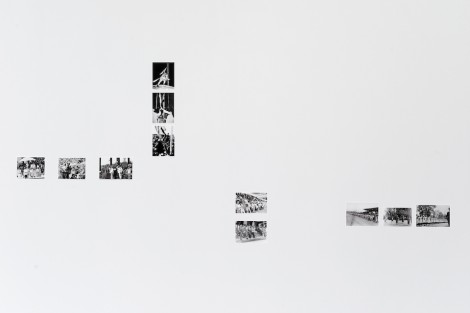

The first thing that you notice when stepping into the gallery, is the long white wall that runs along the back of the room. On the wall, a series of photographs are pasted in lines that span from one end of the room to the other. The photographs are ordered chronologically, starting from 1934, and progressing through the years and countries as the viewer edges from one side of the wall to the other. The setup is minimal, and forces the viewer’s attention to the pictures themselves.

As I make my way down the wall, it seems as though I’ve travelled through decades in the span of seconds. I see images of important looking men seated around tables in the midst of discussion, women marching in Syria, Burkina Faso, and Burundi, and streets ablaze with rocks and destruction as people riot in Indonesia. The collection is rife with political statements of each society’s social and legal development.

Not every photograph is heavily politicized, though; there are images of festive parties and parades with people dancing in cultural attire. In particular, one photo depicts a lively dance scene in the Philippines, where women and men don their traditional Filipiniana dresses and barong.

The exhibit ranges from the declaration of independence of Ho Chi Minh (1945), to Sri Lanka (1948), and Botswana (1966). Apart from these moments in political history, what captivates my attention is a seemingly mundane image.

The black and white photograph, captioned “VIP Women, 7 August 1960 Ivory Coast,” shows a crowd of well-dressed Ivoirian women sitting comfortably in a stadium. Presumably, the women are watching a sport. One of the women seems to gaze back at me; a sunhat tipped elegantly on her head, her lips are half curled and her eyes bright and kind. If not for the caption stating that the photo had been taken more than half a century ago, I would never have guessed its actual age. The women in the crowd wear recognizable clothes (think Kate Middleton), and it is this familiarity that makes me think that perhaps we are not so different from those that preceded us. History may have changed and new developments may have arisen, but the expression of leisure and humanity are not unfamiliar.

Maximizing the viewing experience of The Day After can only be achieved if the viewer makes an effort to internalize the significance of the photographs. Otherwise, the meaning and story behind each photograph can easily be overlooked, and the experience diminished.

Fortunately, this candid collection of photographs makes it easy for the viewers to become captivated by the story unfolding in front of their eyes. It is an experience which Susan Sontag explains best: “All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

The Day After runs from January 13 to March 6, 2016