[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n 1881, Henrietta Charles wrote a letter to Sir Daniel Wilson, then president of University College. “I beg to claim the right to attend lecture in university college. This right has hitherto been denied to women. Permit me to ask if that is quite just?”

Though at first Wilson staunchly opposed the idea of co-ed learning, years of feminist lobbying eventually compelled him to recognize the right of women to obtain university education. In 1884, University College admitted its first female cohort: a mere nine students.

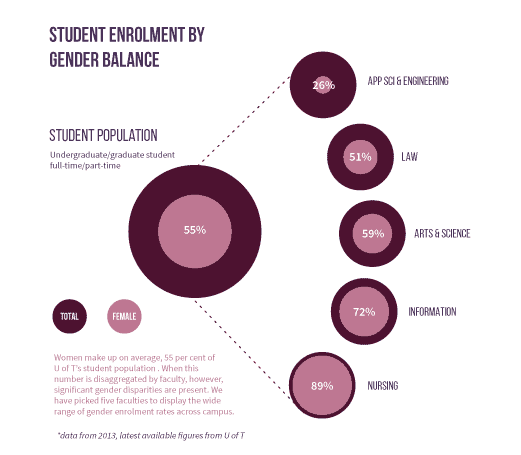

Today, the picture appears drastically different. Women make up 55 per cent of U of T’s student population, and earn over half of the awarded degrees at the undergraduate, masters’, and doctoral level. More broadly, Canada is ranked first in the world for gender parity in literacy rates, along with enrolment in primary and post-secondary education.

At face value, Canada seems to have achieved gender equality in education. Yet, as demonstrated by Wilson’s resistance to open the institution’s doors to women, progress toward gender equality has been and continues to be slow. At Hart House, for example, it took over 50 years for women to gain casual access to the building and facilities without the accompaniment of a man.

[pullquote-image]

Women doing archery at U of T in 1946. Nathan Chan/THE VARSITY

[/pullquote-image]

Remnants of this sexism continue to linger beneath the surface of our institutions in increasingly subtle, but nonetheless powerful, ways. Understanding this past will lend us insight into present activism, and help us to gain a clearer perspective on the issues that remain unresolved. Although thorough, representative discussion of every issue and of every woman’s experience is not possible, leafing through the pages of the feminist movement in the university’s past is a good place to start.

Gendered roles

Throughout the University of Toronto’s history, stereotypes about women were blatant in general discourse, as well as within campus associations. Arguments against co-education assumed that women must remain in their ‘natural’ place, the domestic sphere. “To cram our girls with learning,” one poem read, “you’ll make a woman half a man…This process is unsexing.”

These discriminatory stereotypes have been slow to fade. Upon perusal of The Varsity’s archives, for instance, we found an article from 1955 that asked male students, amongst other objectifying questions, whether they thought “college girls make good wives,” or whether they were “too smart.” One respondent thought that “the most important female virtue was proficiency over the kitchen stove,” while six other male students claimed that “the best feature in a woman was to do what she was told.”

Even at the height of second-wave feminism in the early 70s, there were students who continued to see women as subordinate. Ceta Ramkhalawansingh, a pioneer of the women and gender studies program, notes how female student politicians in particular often faced taunts that were misogynistic and sexual in nature. “When one of the women who was running for president got up to speak, they’d yell ‘take it off, take it off!’” she recalls.

Similar challenges remain today. Female student leaders continue to face backlash for not fitting the stereotype of a soft-spoken, conciliatory woman. Citing her experiences with public speaking, Daryna Kutsyna, co-president of Equal Voice U of T, explains how, while her male peers are praised for their strong delivery, she has frequently been told to tone down her voice or not come across so “bitchy.”

“It definitely makes me feel like I have a smaller range of expressing myself than my male peers,” she says. “Like my workplace performance depends more on my agreeability than my merit.”

Khrystyna Zhuk, president of the Innis College Student Society, and an Arts and Science director for the University of Toronto Students’ Union (UTSU), has had similar experiences. “As a woman, you have to work much harder to be taken seriously and can only express your opinion in a certain way for it to be valued,” she explains. “Women who are outspoken, opinionated and [who] challenge the way that the system works often get shut down and labeled unreasonable, angry, and unprofessional.”

Karina*, another woman in student governance, spoke of a particularly blatant case of dismissal based on gender. When coordinating logistics with an event participant or university administrator, she often “cc”s other executive members — who happen to be male — to keep them in the loop. Some replies to her emails, however, were subsequently directed only to the male executives, removing her from the email chain completely.

“I can’t even communicate with a person because they would rather respond to male students who are peripherally involved than work with me,” Karina says, expressing frustration at the frequency of these incidents. “I think as a female on campus you have to be prepared for people to assume you’re less competent and to have less faith in your ability to contribute.”

There is growing academic study within cognitive psychology that identifies such implicit biases as manifestations of a broader and persistent trend of everyday sexism, making it difficult to dismiss these experiences as outlying extremes.

Mayo Moran, provost of Trinity College, and the university’s first female dean of law, points to research that has been done at the university to shed light on the validity of these claims.

“There’s been very good research done at the business school, at the law faculty,” Moran notes, further outlining that universities, as “repositories of knowledge” have typically been at the forefront of explaining and devising strategies for combatting subtle gendered discrimination.

The first step, however, is to recognize the fact that a problem still exists. “I don’t think it’s something we should have to deal with but it’s also not something that will change [overnight],” explains Karina. “I just wish people would acknowledge that it’s a reality.”

The higher, the fewer

Women’s equality at the faculty level has experienced similar progress, but it has not been without its obstacles. Early hiring practices in the late 1920s — backed by provincial governmental policy — were founded upon the stereotype that women made better wives than professors. In fact, in 1931, the University’s Board of Governors explicitly declared that it was “undesirable to employ married women in the university.” Even after World War II, several department heads were notorious for keeping their staff as a literal ‘old boys’ clubs.’

As such, the university once seriously lacked a visible presence of women in senior positions. Dr. Kay Armatage, professor emeritus and a founder of the women and gender studies program, notes that when she came to U of T in 1965 there was only one female English professor. Similarly, Moran recalls speaking to female law graduates from the 50s and 60s who grew up not knowing any female lawyers, judges, or professors.

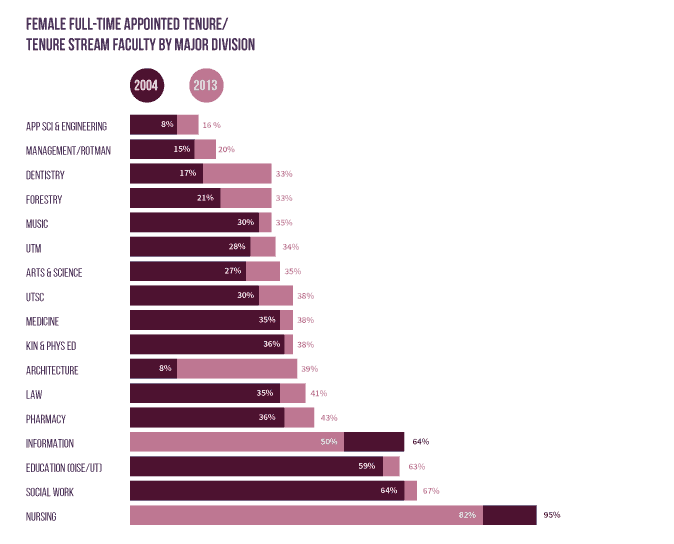

*Dalla Lana School of Public Health not included because no 2004 data available; it became a faculty in 2013.

The university has seen a steady increase of female faculty through the years; from 2004 to 2013, the percentage of full time tenure stream professors increased from 19 to 27, and associate professors increased from 37 to 41. Among other benefits — such as promoting more diverse syllabi and perspectives in academia — the presence of more female faculty can create a stronger network of role models for female students.

“I do think it is incredibly important for people to see people who are like them who can succeed,” explains Moran. “The thought of saying: ‘I can do this’ is so much harder if you don’t have anyone to look to and say ‘I could be like that!’”

In certain ‘male-dominated’ disciplines, the need for mentorship may be even more pressing. “We know that some girls have a difficulty imagining themselves as engineers primarily because of the small number of women role models in engineering,” says Dr. Cristina Amon, the first female and current dean of applied science and engineering.

Notably, however, the engineering faculty has consistently made a concerted effort to increase gender diversity — this includes the promotion of various networking and informative programs, such as the Young Women in Engineering Symposium and the Girls in Leadership Engineering Experience.

[pullquote-image]

Women make up on average, 55 per cent of U of T’s student population . When this number is disaggregated by faculty, however, significant gender disparities are present. We have picked five faculties to display the wide range of gender enrolment rates across campus. Jasjeet Matharu/THE VARSITY

[/pullquote-image]

As for employment practices, the U of T Human Resources & Equity Division has various formalized initiatives to promote diversity. “The push is very much on being proactive, to make sure that everyone is well educated on proper process,” says Katy Francis, director of strategic communications at HR & Equity. She highlights that the U of T recruitment network meets monthly, with representation from all of U of T’s divisional offices, so as to “promote best recruitment practices as well as share ideas, resources and learn from guest speakers.”

For instance, Francis identifies the language used in human resources as a “big topic” of concern — care is taken for job descriptions to reflect flexibility in work hours and respect for work-life balance, while documents should be mindful to use gender-neutral pronouns.

Noting that she was appointed dean around the same time as Amon and Dr. Catherine Whiteside, the first female dean of medicine, Moran explains that she sees her appointment as part of a tangible shift: “this signalled a commitment on the part of the university to look hard and to promote women, including into areas where women had never been as numerous [or] as powerful.”

There remain, however, murky questions concerning pay equity. “Research across North America shows that…Women faculty tend to be paid less than men with similar qualifications,” explains Dr. Sylvia Bashevkin, a professor of political science who specializes in women’s politics. “This affects not just the current income of female professors but also their pensions later on, not to mention their internal standing within departments and potentially their sense of self worth.”

But the picture at U of T remains unclear. In a 2010 study, the U of T faculty association found that female faculty were indeed being paid less than their male counterparts in all professorial streams. Due to aggregate numbers, however, they could only tentatively conclude that “in a number of areas there appears to be gender salary discrimination.” When asked about what steps are being taken to identify and address any existing pay equity, Francis said the university “does engage in periodic analyses of salary data” and that “[d]ifferences in salary that are not explained through [factors like discipline, rank, history of merit awards, etc.] Will then be subject to further analysis.” Unfortunately, there was no indication that these analyses would be made public.

One of the most notable compensation disputes occurred more than twenty years ago, after the Ontario pay equity act was passed. “In 1989, I was $10,000 dollars down from my male equivalent,” says Armatage. “I got [compensation] retroactively [for] two years. But I had been teaching full time for more than 10 years, nearly 15 years. So, had they had to go back and pay me equally for all that time, it would’ve been a bundle!”

Subsequently, in 1991, the university adopted an Employment Equity Policy; three years later, they settled a class-action lawsuit in which retired female faculty — who were not included in the 1989 compensation review — alleged “the university had been unjustly enriched by paying them less than men performing the same work.” Unlike the University of British Columbia and Mcmaster University, U of T has not had any compensation initiative for female faculty in recent years.

“Pay women faculty members equal to men,” says Armatage when asked what the university should be doing to contribute to feminism. “There is not equality if women are considered secondary workers.”

The logic of gendered violence

Perhaps the most concerning issue for women on campus is violence. Instances of extreme physical violence — such as the murder of fourteen women and serious injury of many others, at l’Ecole Polytechnique de Montreal in 1989 — seem to be considered anomalies we need not worry about today.

Yet, doing so ignores how anti-black and transphobic police brutality continue to touch the lives of many female students, while the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women has only recently received government attention. Rates of sexual assault at universities also remains a concern.

This is not to mention that gendered violence exists on a coercive continuum. From death threats to harassment to domestic abuse, it is used to scare women, particularly those who challenge the status quo, into silence and subordination.

Most notably, last year, the university was shaken when explicit, violent death threats made against U of T feminists, and the equity and women and gender studies departments, appeared online. Though many were surprised at the vitriolic nature of the posts, campus feminists regularly face such threats.

Last summer, Celia Wandio, a fourth-year student at Trinity College, wrote an article for The Varsity on why it is important to believe survivors of sexual assault. In response, one user published a comment explaining at length why Wandio was “worse than a murderer,” while another penned an anonymous blog post using Wandio’s full name, viciously attacking both her arguments and her person.

Nish Chankar, associate vice president equity of the UTSU has also received hate mail from men’s rights activists in response to an article she wrote for The Varsity, detailing her opinions on the problematic nature of these groups.

Moreover, Jades Swadron, a third-year student, explains that she, as a trans woman, is particularly visible for perpetrators of gendered violence. Alongside other factors on campus that make trans persons feel unsafe — such as washroom inaccessibility — Swadron has been subjected to verbal and sexual harassment, and has also received death threats from anti-feminists.

To outside observers, online bullying and attacks may seem mostly benign — annoying rather than seriously impactful — yet, they are often rooted in the maintenance of unequal power dynamics. Whether or not this is the intention behind those actions, their consequences are notable and concerning.

“One of the ways of discounting what people are trying to do is put labels on them and undermine the intent,” says Ramkhalawansingh, referencing early anti-feminist dissent to the establishment of a women and gender studies program. Such name-calling and threats were expressions of aversion to challenges of the status quo. “When you start wanting to change power relationships and changing the distribution of power… it does make people uncomfortable,” she explains.

Chankar expresses similar sentiments: “Why is there so much pushback? Because we’re winning. Because feminists are making a difference.”

So for all the resistance to gender equality, it is clear that feminists on campus are still determined to soldier forward. While considerable progress has been made in breaking down legal and cultural barriers, there is an understanding that students must remain vigilant and avoid complacency in the face of work left to do. While this road to gender equality is arduously long and not one “strewn with roses,” it is certainly one we must continue to tread.

*Name changed at student’s request