This is the second installment of a two-week feature on the history of feminism at the University of Toronto.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]hough feminism has succeeded in recognizing students’ rights, the movement continues to be mired in stigma. Among many other labels, it has faced accusations of irrelevancy, misandry, and exclusivity. For these reasons, and for others, for better or for worse, many students remain hesitant to claim the title of ‘feminist.’

Delving into the history of feminism can help us understand not only how we reached this point, but also give us a clearer sense of the movements future prospects. We spoke to students and staff to explore the multiplicity of feminism within our diverse student body, the potential it holds to improve our lives, and the internal obstacles it must overcome in the years ahead.

Defining feminism

Feminism, in basic terms, is best described as a movement for equality between men and women. This idea is easily traced throughout the movement’s historical development.

“Research shows there have been waves of feminist activism,” explains Sylvia Bashevkin, a professor of political science at U of T. “The issues emphasized in each successive wave may change, but there remains an underlying commitment to drawing out the dynamics of gender inequality and pressing for fairer opportunity across time.”

Specifically, the women’s movement in Canada is often divided into three “waves.” In the early 1900s, women rallied for various civil rights, such as suffrage and the right to hold political office. This activism relied heavily on notions at the time of women as natural caregivers, who could offer a distinct and beneficial nurturing perspective in public life.

After World War II and the consequent erosion of strictly gendered workforces, feminism saw its second wave emerge in the 1960s and 70s. With broadened notions of equality, activists scrutinized how oppression manifested subtly in socio-cultural planes — such as the media and school curricula — while continuing to challenge legal discrimination concerning areas such as pay equity, sexual assault, and abortion.

Today, activists often speak of working with the “third wave” of feminism, which describes a more concerted focus on breaking down the gender binary and increasing consideration of how multiple identities of race, age, class, and sexuality affect women’s experiences.

While the “waves” framework holds a lot of currency in mainstream Canadian media, many have critiqued it for being rooted solely in Anglo-European history and thus failing to recognize the myriad other stages upon which women have fought against gender inequality.

“I think the ‘waves’ are good intros, but ultimately take away from some of the variations and nuances of feminist organizing,” says Ellie Ade Kur, a PhD student in human geography and a feminist organizer. “They find ways to boil decade-long struggles down to one or two issues, which can be helpful for people new to feminism and the history of feminist thought. But not really helpful in understanding how complicated these kinds of movements are.”

Investigating the dynamics of colonialism in Canada can help to highlight where the “waves” framework falls short. For instance, Indigenous women’s resistance to the 1867 Indian Act — which has long been associated with the imposition of patriarchal oppression upon relatively egalitarian Indigenous communities — cannot be easily slotted into any of the three waves indicated above.

The inherent duality presented by classic conceptions of feminism can also be problematic. Stating that women are ‘just as good’ as men shifts the focus away from creating an inclusive and representative space for women based on their individual identities. An emphasis on equality between men and women also excludes the experiences and perspectives of those who do not identify within the gender binary.

“There’s always just the general question of inclusion: where are queer, Black and Indigenous voices? Where are the voices/ideas of women facing multiple forms of marginalization?” asks Adekur.

What seems to be constant within feminist movements, however, is the fact that they embody a challenge to the status quo. “Ideally, feminism is a resistance and a criticism of hegemonic social structures,” explains Jades Swadron, a third-year student, who notes how her activism works towards dismantling not only the patriarchy but also systems of oppression based on class, race, and sexuality.

“Feminism isn’t just about women, it’s about transformation of world order,” states Ceta Ramkhalawansingh, a U of T alumna and a founder of the women and gender studies program. “Not just for women but for everybody.”

Resilient revolutionaries

The strategies employed by feminists in order to achieve their goals vary just as widely as conceptions of feminism itself. Feminists have a long track record of mobilizing for social change, and earlier methods to create this change were particularly daring.

In 1957, for instance, a group of female students disguised themselves as men in order to enter Hart House and watch John F. Kennedy participate in a debate. While a glimpse of one student’s nail polish ultimately led a security guard to realize they were women (and subsequently kick them out), the act helped to highlight Hart House’s archaic rules.

“It was definitely a political statement,” says Judy Sarick, one of the participating students and former reporter for The Varsity. “This was before the feminist revolution when there was little institutional support for women. It was up to the individual to be as brave as she needed to be.”

Abortion was also a key issue for feminists on campus. During the 70s, distribution of information about abortion was prohibited; yet the Student Administrative Council (SAC) — predecessor to the UTSU — circulated thousands of McGill Birth Control Handbooks containing information about abortion anyways.

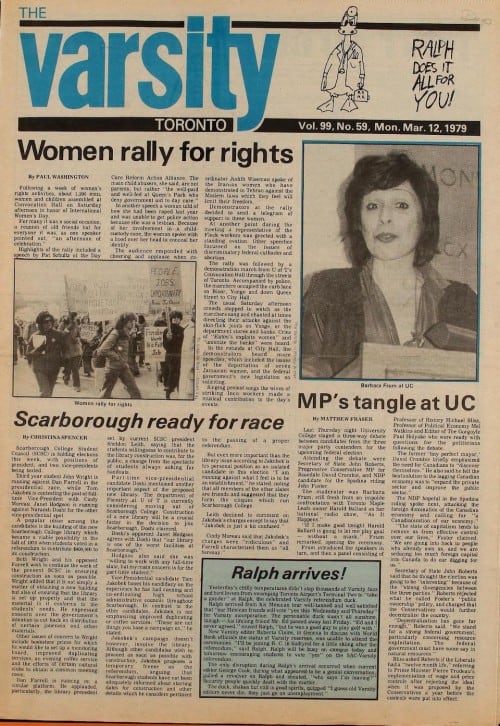

What’s more, the SAC rented buses to enable students to join the infamous Abortion Caravan, which drove to Ottawa to demand the legalization of unrestricted abortion services access. This constituted Canada’s first national feminist protest and gained widespread media attention when protesters chained themselves to their seats in the Parliamentary gallery.

In a similar vein, former editor-in-chief of The Varsity, Linda McQuaig, went undercover posing as a pregnant woman to “expose the coercive tactics used by a campus Catholic organization that was purporting to offer students abortion counselling.”

“Although things started off calmly,” recounts McQuaig. “I was soon told that if I decided to have an abortion, I would have to live with terrible guilt all my life because I would always know that I had killed!”

Perhaps most notably, however, is the cheek within which Ramkhalawansingh and Armatage advocated for the establishment of an official women and gender studies program. They pored through the Arts & Science calendar, cutting and pasting existing courses that might have anything to do with women and gender studies into an unofficial brochure. After sticking a U of T crest on it, they distributed the brochure all over campus.

“We got called into the dean’s office,” recalls Kay Armatage, a professor emeritus and pioneer of the women and gender studies program. “The dean was very, very forceful about it. He said ‘This is not the way we do things at the University of Toronto…if we are going to start a program in Arts and Science, we first form a committee to look into the matter.’” And so they did; in a year after that event, the women and gender studies minor had been established.

“It was totally guerrilla tactics,” remembers Armatage. “It worked out very well, even though I was shaking in my boots… being reprimanded by this very tough person.”

By the early 2000s, the heyday of radical student activism had seemingly passed, yet the question of whether feminism is still present on university campuses remains up in the air. Ramkhalawansingh, for one, thinks it has simply changed forms.

“When you become institutionalized and become part of the structure, the way in which you mobilize is very different,” Ramskalawansingh explains. “…[Y]ou become part of the bureaucratic process…[T]here are offices to deal with these issues now.”

Even the quickest survey of the university’s diversity & equity page confirms this, with offices for Sexual & Gender Diversity, Sexual Harassment, and Family Care figuring prominently. This is not to mention the advisory committee to the provost, which was struck last year, that was aimed at preventing and responding to sexual violence.

This is not to say that grassroots activism has completely faded away. In response to the death threats made against U of T feminists and the equity and women and gender studies departments last fall, hundreds rallied to protest misogyny in its modern manifestations. Moreover, there has been growing student pressure on the administration to pay more attention to sexual violence on campus.

Intersecting narratives

Despite these changes, a significant problem within the movement continues to demand attention — namely, how to ensure that those women who are marginalized on planes other than gender have their voices heard. It is this distinction that some believe has contributed to the weakened feminist presence on campus.

“If you try and see what progress is like for people of colour, queer and trans people, especially trans women, and in more particular fields,” Swadron explains, “…you will start to question if the changes since then have been all that pronounced.”

Adekur has also had many personal experiences with this lack of inclusivity. As the former Internal Liaison Officer for CUPE 3902, she recalls receiving targeted messages harassing her after speaking out about equity issues in the union, only to be told that “being so vocal and ‘combative’ about ‘contentious issues’ has its consequences.” Yet, when white female members received impersonal harassment regarding a union policy, the organization immediately went to work on an online harassment policy.

“It’s about whose voice is taken seriously, whose pain we choose to believe and how our sympathy is so unevenly spread,” she explains. “I used to ask white men in my union to literally repeat the words I said so that the same audience, hearing the same point, would take my thoughts and ideas seriously.”

In another instance of racialized sexism, a professor at a sociology conference approached Adekur and insinuated she “probably [knew] how to work a pole” since she studied sex work. He then offered to be her mentor — citing his expectation that black women needed support and guidance in academia. “…[T]hat story is a very real example of how young, black women and our bodies are sexualized and the kind of liberties people feel they can take,” Adekur says.

Unfortunately, the feminist movement often mirrors society at large by dismissing and even perpetuating these manifestations of discrimination. Swadron cites being made to “testify” about her experiences to cis women, who often do not see that she, as a trans woman, is just as much a part of the feminist movement as they are. Not only does this attitude simply add to the discrimination and hostility trans students often face on campus, it also negates the equity-orientated basis that feminism claims to rest upon.

Women of colour also face distinct marginalization in feminist discourse. Women’s right to vote in Canada, for instance, is often dated to the early 1900s. Yet, this erases the fact that Indigenous women’s unconditional right to vote was only recognized in 1960, only slightly more than 50 years ago. The overwhelming emphasis on women’s right to abortions also tends to obscure the other side of reproductive rights — that is, the right to bear children — which, historically, has been denied to Indigenous women via government-mandated sterilization initiatives.

This sidelining of racialized women manifests frequently in feminist organizing on campus as well. Nish Chankar, associate vice president, equity of the University of Toronto Students’ Union (UTSU) and co-president of Trinity’s Students for Gender Equity, notes that the speakers at the feminist rally last fall were “disproportionately white.” In particular, the “white saviour comments” about women in Afghanistan — made by keynote speaker and New Democratic Party candidate Jennifer Hollet — were, she felt, framed in such a way to distract from persistent gender equality at home.

“It’s disheartening to go to events like this, as a racialized woman, that aren’t necessarily for us,” Chankar says. “It’s not about there not being enough racialized feminist speakers on campus, because there are — it’s that not enough action was taken to make the rally as inclusive as every feminist rally should be.”

Similarly, Bosibori Moragia, a second-year English literature and African studies student has “been in situations where mine and other black women’s complaints have been silenced because they’re seen as derailing tactics.” She explains that the distinct problems that black women try to bring up are often pushed to the bottom, or even off, the feminist agenda. “It feels like what we’re really being fed is the age old adage that our ‘negro’ issues will be attended to as soon as white women have their emancipation,” she explains.

As a result, some have made calls for a more intersectional approach to feminism.

“Womankind has a plethora of members who fall into different categories and identities. These criss-crossing identities ultimately determine how they move through the world as a woman,” Moragia explains. “Intersectionality is about meeting people where they’re at and casting away the idea that there are ‘one size fits all’ approaches to fighting the patriarchy.”

“Intersectional feminism is all about acknowledging what it means to occupy a number of marginalized identities — what it means to be a queer, trans, racialized woman, or a woman living with a disability, for example,” says Adekur. “Intersectional feminism should really be the movement we default to when we think about feminist thought and action.”

The road ahead

Moving forward, there is plenty of opportunity at U of T to bolster this feminist change. As an educational hub, the institution has the capability, and likely, the resources, to unpack and combat inequality through research.

Ramkhalawansingh notes how, when she and Armatage first attempted to create a curriculum for the women and gender studies program, women were invisible from public records. This gender bias can have disturbing consequences for academia — for instance, the failure to acknowledge women’s participation on the farm in the 1911 census meant that female agricultural labour was written out of history.

The creation of the women and gender studies program has helped to remedy some of these gaps in academia, while feminist scholarship within other programs have challenged mainstream narratives. “Early in my career, it was clear that the category of gender was not accorded academic importance,” recalls Bashevkin. “This pecking order has shifted over the years.” Recently, editors of a leading international reader on US foreign policy invited Bashevkin to contribute the first ever chapter on gender to their book, which will appear in 2017 — an invitation that, Bashevkin says, “constitutes one small but telling signal that older patterns may be changing.”

The development of more wholesome analyses of society are doubly important, given that university research often influences public policy. “I think we [as a university] have an obligation to say ‘Let’s share our great knowledge, let’s make sure that opinion leaders and decision makers know,’” says Mayo Moran, provost of Trinity College and first female dean of the law faculty. “…I believe knowledge is the fundamental springboard of change and values.”

Students themselves have a plethora of suggestions for what directions campus feminism can take going forward, ranging from developing a sexual violence policy to implementing quotes for women in leadership positions, or even the creation of a feminist UTSU slate. While the details may differ, the general consensus seems to indicate that feminism still has a significant role to play on campus, and the aversion towards the movement is no reason to stop organizing.

“There has not been a single meaningful social justice movement that was initially received by open arms,” explains Chankar. “Society isn’t as malleable as we think, and change needs to be gradually accepted… So we’re not stopping anytime soon.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated from an earlier version.