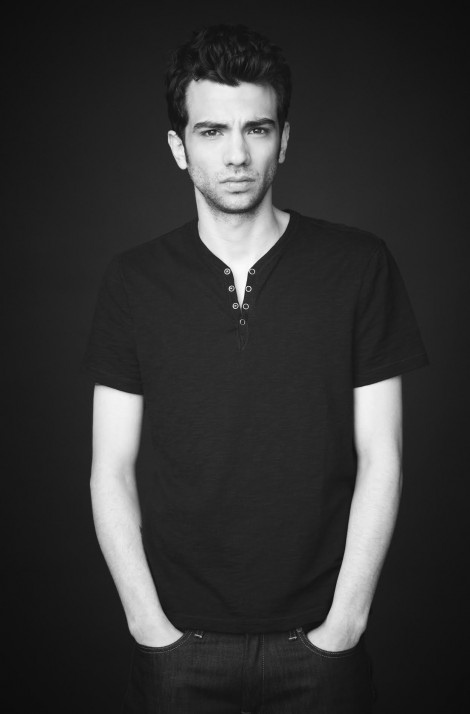

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]S THERE SUCH A THING as a ‘Canadian hero’ in Canadian film? More specifically, where are the Rocky Balboas of Canadian cinema? These are but a few of the questions that were raised during acclaimed actor and director Jay Baruchel’s talk at the TIFF Bell Lightbox last Tuesday.

The focus of his discussion was heroism in Canadian cinema — citing Goon (2011), a film about Doug Glatt, a fictional minor-league hockey player — Baruchel emphasized the significance of athletes in garnering the affection of a nation. “The players in bright color shirts that represent your town or your country allow you to project your own thing on them” says Baruchel.

He jokingly notes that in Canada, “patriotism happens only every four years.”

According to Baruchel, introducing a hero like Glatt in a Canadian film is helpful in augmenting the popularity of Canadian films worldwide. Many of the critically-acclaimed Canadian productions, like David Cronenberg’s psychologically-driven science fiction dramas or Guy Maddin’s cynical depictions of Winnipeg, are often marketed as complex ‘art films.’ These films lack the optimistic protagonist with which most viewers empathize. After all, the most commercially successful Canadian film in history was the 2001 film My Big Fat Greek Wedding, which comically explored the cultural differences that many Canadians know and experience.

The concept of a Canadian hero in cinema is not a recent phenomenon. Baruchel notes that, despite the lack of Canadian heroism, the topic has been of interest to film enthusiasts and historians since the 1960s. Christine Ramsay, a film critic, extrapolates on the trope of failed masculinities in Canadian cinema by using Donald Shebib’s 1970 film Goin’ Down the Road as an example. Shebib claims that unlike our neighbours down south, Canadians are preoccupied with survival rather than heroism and tend to explore socio-cultural margins rather than idealized promises of a bright future. Similar to Glatt in Goon, the two men in Goin’ Down the Road travel to the promising city of Toronto; unlike the hero in Goon, they fail miserably.

Goon diverges from the cynicism of Goin’ Down the Road in its uplifting and optimistic mood, yet that does not indicate that the film adopts American idealism, or that it sugarcoats the realities of this brutal sport.

“There’s something beautiful in a guy who is willing to risk everything for what’s right,” says Baruchel. Although Glatt is more a fist-fighter than he is a hockey player, Baruchel suggests that his reliance on violence is still important for the team, and generates audience excitement and support. Baruchel clarifies that his crew attempted to romanticize violence rather than glorify it in order to convey this uniquely Canadian experience.

Baruchel feels that the lack of Canadian heroism outside Goon implies that in Canadian cinema, “it is better to be a failure rather than a show-off.”

Baruchel also holds that we should not be afraid to tell Canadian stories. Featuring a truly Canadian hero, or even an authentic locale, is often problematic in contemporary national films. As Baruchel notes, many films made in Canada have a strong dependence on American preferences; despite featuring local talent, Canadian filmmakers are often heavily funded by the US investors.

While Baruchel’s presentation could not quite answer the profound cultural questions raised regarding our national cinema, it highlighted some disparities between Canadian and American cinema. While Canadians can claim filmmakers like Cronenberg, Atom Egoyan, and Denis Villeneuve as our own, Americans can claim fictional icons like Rocky Balboa, Indiana Jones, and Forrest Gump as theirs.