Whereas justice precludes the concentration and abuse of power in the hands of a few, the pursuit of justice necessarily conflicts with ‘peace’ — otherwise known as the status quo. Often, radical visions of an alternative society are dismissed as violent, chaotic, and simply not attuned to ‘compromise’ between the haves and the have-nots; and so, struggle is reduced to reconciling binaries rather than transcending them altogether.

The subject of feminism — like many heavily debated topics — is disappointingly reduced to two poles in popular discourse. On one hand, there are the exclusionary conservatives like Milo Yiannopolous, who un-ironically depict feminism as a ‘feminazi,’ ‘man-hating’ conspiracy against which we need to defend ourselves. On campus, such thought has gained traction in recent years, illustrated by men’s rights groups and recent ‘free speech’ rallies that refuse to respect the fluidity and self-determination of gender.

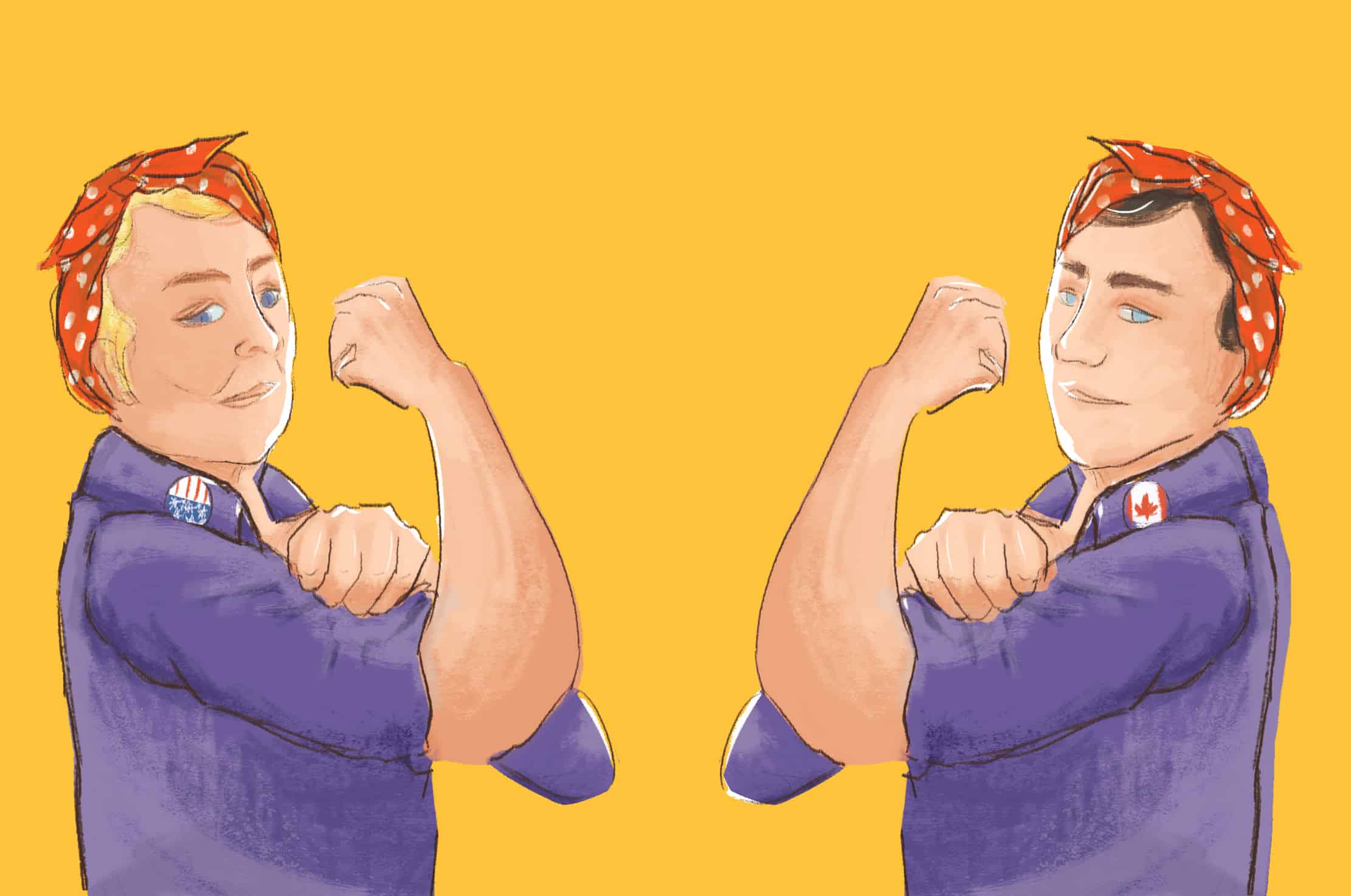

On the other end, there are the ‘inclusionary’ liberals. Justin Trudeau, — the man who championed gender parity in cabinet last year, — ostentatiously prides himself on being a feminist. Hillary Clinton ran a campaign on prospectively being the first woman President of the United States. This version of feminism, which attempts to implement equity while preserving traditional institutions of power, is simple enough for so-called ‘progressive’ elites and masses alike to support.

However, both these perspectives are limited, and ultimately anti-feminist. The errors of the first are clear. Gender is constructed and reinforced by society in a way that favours masculinity and burdens female and non-binary genders with unique lived experiences. From the gender wage gap, to the assault on abortion rights on campus and beyond, to the rape culture that thrives in the acquittal of prominent figures like Jian Ghomeshi, we are no doubt far from any sense of gender ‘equality.’ To depict feminism as ‘feminazism’ reveals an anxiety possessed by the ideologues who use this phrase: that of a future that deconstructs masculinity and the power associated with it.

The more complicated criticism is directed at the ‘liberal’ view. Figures like Margaret Thatcher, Clinton, and Trudeau will be memorialized for ‘including’ the female gender in positions of power. But this is mere tokenization, by which femininity is assimilated into literally man-made institutions that are adversarial not only towards women, but toward human dignity in general. Consequently, we should think critically before applauding them.

Thatcher crushed labour unions and workers’ rights in her days – compromising working-class families and the women at their centres. Clinton committed hawkish imperialism as Secretary of State that has harmed women of colour abroad. Trudeau has funded billions in an arms deal to Saudi Arabia — one of the most misogynistic regimes on the planet. Even female leaderships in the Global South, from Indira Gandhi to Sheikh Hasina, have arguably disadvantaged the marginalized people in their respective electorates.

In all, whereas feminism fundamentally represents the pursuit of human dignity, institutions and leaderships that are corporatist, imperialist, and elitist in nature are only deceptive shells of what ought to be a broad, inclusionary, and intersectional movement.

In Canada, too, the dialogue about feminism needs urgent re-shaping. Indo-Canadian filmmaker Deepa Mehta recently premiered her film, Anatomy of Violence, at the Toronto International Film Festival. Although the subject matter was the 2012 gang rape of an Indian woman in New Delhi, Mehta refused to re-victimize the victim; it did not focus on the woman or her trauma. Rather, the film humanized the men by speculating their impoverished upbringings and abusive relationships. Mehta’s attempt to show patriarchy as a structural problem — as a problem that needs to focus on the construction of masculinity and its impact on men — is commendable, and she insists it speaks to Canadian society too.

The International Relations Society at U of T recently hosted Dr. Joan Simalchik – coordinator of the Women and Gender Studies Program at UTM – in a discussion on the intersections between gender and conflict, much of which focused on pertinent issues of sexual violence and repression in peripheral countries: Syria, Iran, Chile, Dominican Republic, Rwanda, and Bosnia. In line with Mehta’s film, such discussions are important. However, it is too easy – and deceptive – to re-direct focus on the ‘rest’ of the world; to self-declare the West as already ‘achieving’ feminism, and to depict the fates of women elsewhere as helplessly oppressed.

Nothing is further from the truth, for the ‘liberal’ Western public has its own issues. For example, Canadians’ apparently progressive reactions to Donald Trump’s comments on women during the election, included attempts to differentiate ourselves from the United States and were often framed using possessive and relational descriptions of women, where men remain dominant to power and dialogue. Instead of acknowledging threats to women’s dignity and humanity, we tend to frame issues with reference to how ‘our’ women would feel, and are told to think about ‘our’ daughters, wives, and sisters as potential victims.

[/pullquote-features]

Feminism must be re-framed revolutionarily. It cannot be a tool for institutions to appear to diversify themselves while committing patterns of injustice, and it certainly cannot be centred around men, who are the people in power of those institutions. To create more just societies, women must be granted the agency and self-determination needed to create just institutions from scratch.

Notably, the most formidable examples of this are women of colour who are furthest from the attention of power and popular discourse. This includes Indigenous women in Canada, who are at the frontlines of struggles against neocolonial development projects; Black women in the United States and Canada, who make up the core of the Black Lives Matter movement; and the Kurdish women of Rojava, fighting ISIS and simultaneously building multiethnic socialism.

Where feminism means human dignity for all through the deconstructing of masculine systems of power, the binary of ‘feminazism’ and ‘liberal tokenization’ that dominates popular discourse is a fallacy. Feminism must account for the dismantlement of all dehumanizing institutions of power — including racism, imperialism, and capitalism — all of which affect women the most.

In this context, men who envision a more just society, even with good intent, must also acknowledge the positions of power they have exclusively monopolized. They cannot be the ones to lead that struggle, for it must be marginalized groups who re-create a world in which their communities and selves are their own to define.

Ibnul Chowdhury is a second-year student at Trinity College studying Economics and Peace, Conflict and Justice Studies. He is a columnist for The Varsity.